Colombia starts ceasefire with nation’s oldest rebel group

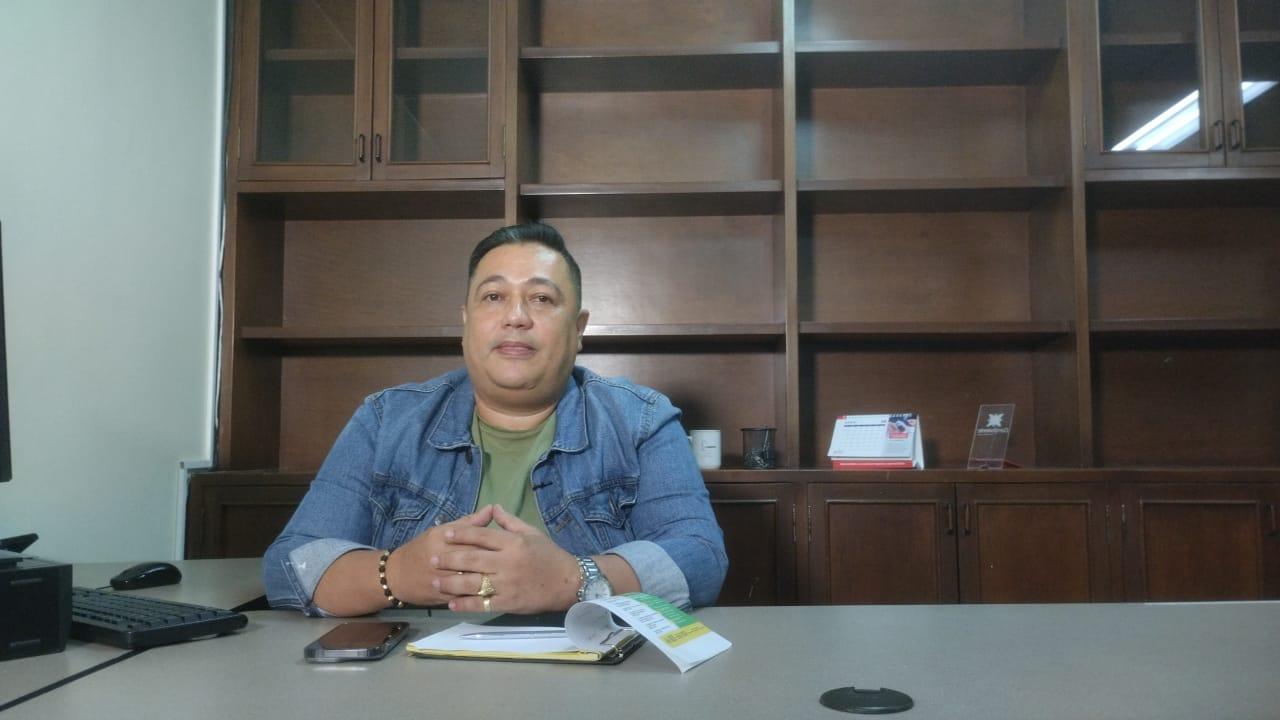

Nelson Leal is a mayor who can’t work in his own town. Two years ago, he was elected to lead Tibu, a town of about 60,000 people near Colombia’s border with Venezuela.

But he had to flee in March due to death threats from the National Liberation army and other rebel groups that are vying for the control of drug-trafficking routes around Tibu.

So now, Leal carries out his mayoral duties from Cucuta, a larger city that is about four hours away, and where he gets around in a bulletproof vehicle.

“I’m not the only one who is absent,” said Leal, who works in a small office that was lended to him by the local governor. “There is no prosecutor there, or any courts. We have no human rights ombudsman and although we are on the border with Venezuela, there is no border post.”

Leal said he is hoping that a ceasefire that began this week between the Colombian government and the National Liberation Army — known also as the ELN — will make it possible for him to return home and for more government agencies to work in his town to tackle problems such as poverty and crime.

The ceasefire is expected to last six months and seeks to boost ongoing peace talks between Colombia’s government and the ELN, a rebel group of Marxist orientation that has been around since the 1960s.

The truce is part of President Gustavo Petro’s plans to pacify regions of the country that are still affected by rebel groups and drug cartels. Some of these groups have become more powerful recently because they occupied areas of the country that were abandoned by the FARC, a guerrilla group that made peace with the government in 2016.

For Leal, the ceasefire with the ELN provides some hope that things might change in his region where rebel groups impose curfews in villages; tax local businesses; and threaten those who get in their way.

As part of the ceasefire, both sides have also agreed to stop attacks on civilians.

“Those of us who live in areas affected by conflict want peace,” Leal said. “I hope that they stick to what they have agreed to.”

But not everyone agrees that granting the ELN a six-month break from persecution by the nation’s military is the best approach.

In the past, other rebel groups in Colombia have taken advantage of truces with the military to increase their drug-trafficking profits and buy more weapons. Then, they’ve gone back to war when they weren’t satisfied with what was being offered to them at peace talks.

Last month, thousands of people turned up at a rally in Bogotá to protest against Petro’s security policies — including the ceasefire.

“Everyone wants peace,” said Guillermo Rojas, a retired police officer who attended the rally. “But you can’t give a criminal group so many advantages at the start of talks. The government is throwing away its leverage.”

Petro, who was once a member of a rebel group himself, said that the truce presents an opportunity to build trust with the ELN and provide some relief to areas of the country affected by violence.

Petro, during a recent visit to Arauca, another region affected by fighting, was greeted warmly by locals who swarmed around the president to shake his hand and get his autograph. As he spoke to the crowd, he urged the ELN rebels to lay down their weapons and take the truce seriously.

“Leaving your machine guns behind is the most-revolutionary step you can take,” he said. “You need to give the people the chance to decide their own destiny and create their own history.”

As the peace talks move forward, the ELN has hinted that it wants to see changes in how Colombia exploits its natural resources, and it also wants reforms to the electoral system. The group’s lead negotiator Pablo Beltran also said on Thursday that Colombia should prioritize spending on social programs over paying back debts to the nation’s creditors.

For the moment, both sides have agreed to create committees in which members of civil society groups like farmers associations or trade unions will be able to provide proposals on how to solve problems such as poverty or crime.

The ELN said that it wants to use the recommendations that emerge from those committees to come up with a more specific list of demands for the government.

That makes it hard to know how long the peace talks could take.

Elizabeth Dickinson, a Colombia expert at the International Crisis Group, said that the only way to increase support for the talks is if the ELN’s attacks against civilians decrease during the truce.

“There is limited patience for negotiations with this organization, particularly, while insecurity continues to increase,” Dickinson said. “If there are incidents that are high-profile, whether it’s recruitment, whether it’s kidnapping, whether it’s businessmen denouncing that there is ongoing extortion, that can easily discredit the talks in ways that limit the government’s capability to keep sitting at the table.”

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!