Migrants from northern Africa make dangerous trek through Spain’s Canary Islands

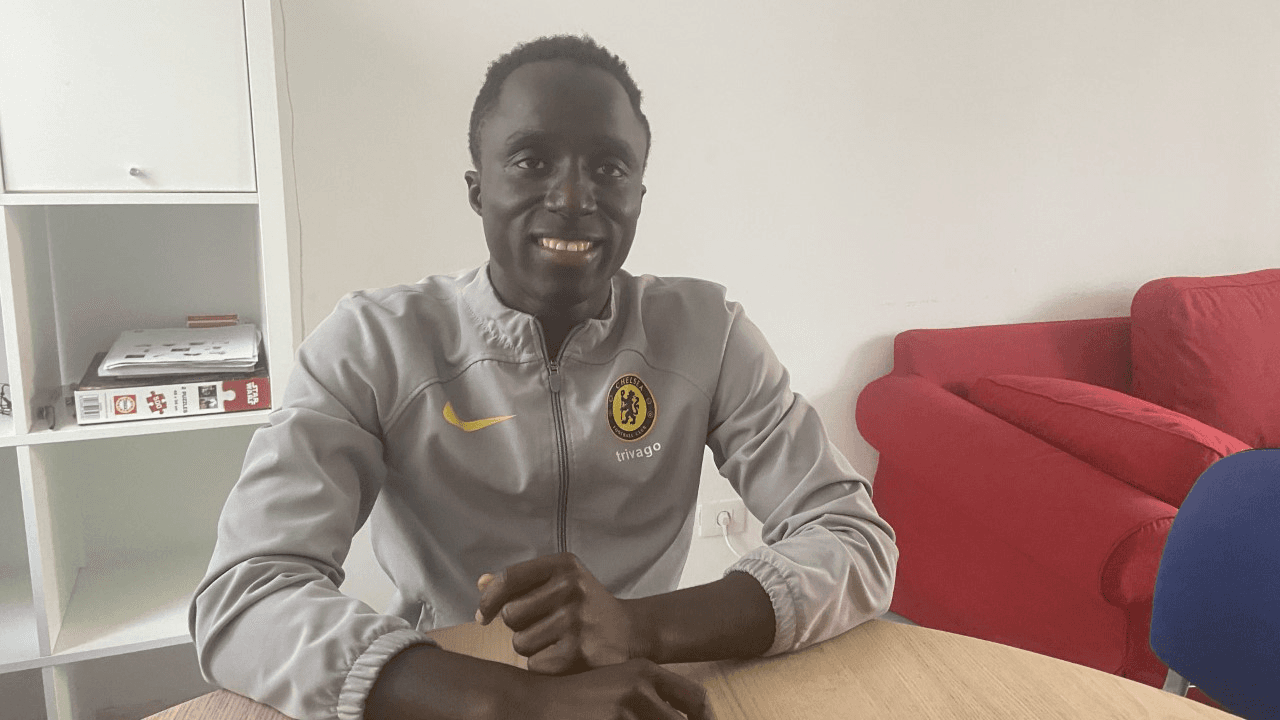

Senegalese teenager Mohammed Mandijj had already been on the road for nearly a year before setting sail from from Western Sahara to Spain several months ago.

He was one of 47 passsengers on a boat that night. Although he said that he feared for his life, he put his fate in God’s hands.

“Once at sea, I thought, I can’t die out here,” he said.

The teenager’s parents had died and his brother was in Italy; he left home to earn money.

Mandijj is among a growing group of migrants from Africa, who, trying to reach Europe without permission, set their sights on the Spanish Canary Islands.

The Canaries begin just 60 miles off of the coast of the Western Sahara, in the Atlantic Ocean. That relatively short distance makes them attractive to those fleeing hardship at home. But the crossing is treacherous and help for new arrivals can barely keep up with the need.

After three rough days at sea, Mandijj’s boat washed up along Lanzarote Island’s rocky coastline. He ended up in a facility for unaccompanied minors. He spoke no Spanish, had no possessions, and he had no plan beyond escaping poverty.

But Mandijj was one of the lucky ones, said migrant activist and attorney, Loueila Mint al-Mamy.

“In the last five years, more than 400 boats have disappeared along with some 11,000 migrants on the Atlantic crossing,” she said. “The boats depend on the currents, and sometimes, they’re swept out to sea.”

And sometimes, they’re smashed against the sharp volcanic rocks that make up most of Lanzarote’s coastline. Boats called pateras in Spanish can be found in and around the island, just listing on the rocks.

Moroccan Boujama al-Maabuub, 29, arrived here on a patera 10 years ago; it made it within 60 feet of the shore before it flipped over.

“I knew how to swim a little,” he said. “But I couldn’t even raise my hands because I was so exhausted after the long trip.”

Maabuub said the water was pulling at his clothes. But in the dark, he found a piece of wood and floated until he was rescued. He was one of eight survivors out of the 27 people on his patera. The rest drowned.

Despite the dangers, the pateras keep coming mainly because the safer routes to Europe have been closed, Mamy said — namely, crossing the Mediterranean from Morocco’s northern coastline to Spain.

“Morocco reached a deal with the European Union earlier this year to close that route,” she said. “Morocco has militarized its northern Mediterranean coast.”

This is pushing people south, to leave from Western Sahara, or even from Mauritania, Senegal or from further afield, she said.

Earlier this month, three Nigerian men survived for 11 days balanced on the rudder of a giant container ship before reaching the Canary Islands.

In 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, when the tourists stopped coming, a record 23,000 migrants arrived, according to Lanzarote activist Silverio Campos.

“During COVID[-19], our seasonal workforce went down, but the pateras kept coming in larger numbers,” he said. “Yet obviously, the people weren’t coming to work. It defies logic.”

COVID-19 devastated the Canary Island economy. But the damage to many African countries was even worse.

Campos heads a government-funded halfway house for young migrants once they turn 18. It’s called Trib Arte. Residents learn basic life skills such as cooking, making tea, and cleaning up after themselves. But Trib Arte has just 12 beds, not nearly enough for the roughly 100 people released each year from the facility for minors.

Mandijj, from Senegal, secured a spot here just a couple of weeks ago.

“Back home. I couldn’t read or write,” he said. “Now, I’m learning Spanish and French. Thanks to these social workers, I am feeling happy.”

Mandijj said he hopes to find a job in a hotel now that the tourists are back.

Campos said that he’s a shoe-in: “Hotel managers and business owners are calling us asking us if our residents can work. When I tell them they don’t have the language skills yet they say, ‘So what?’”

The Canary Islands, and Europe in general, are bouncing back from the pandemic, which is likely to lure more desperate migrants from Africa and beyond.