By the time A. made it to the Kabul airport to evacuate Afghanistan amid the Taliban takeover in August of 2021, it was already too late to say most of her goodbyes in person.

A. was a member of the Afghan military for five years, including three years with an elite, all-women unit called the Female Tactical Platoon, which made her a target for the Taliban.

A.’s full name isn’t being used — only an initial — because some of her family is still in Afghanistan. They’re Hazara, a persecuted ethnic and religious minority there. A. said that talking about her work could put them in even more danger.

That day at the airport, “I called my parents. I said, ‘I’m sorry, because I didn’t [see] you guys, and I’m getting ready to go. I’m leaving Afghanistan,’” she said.

It was the first time that she’d heard her dad cry, she said. “He said, ‘I love you,’” A. recounted recently, from Tempe, Arizona, where she shares an apartment with two other women from the same platoon.

A. and her roommates are among nearly 40 platoon members who made it out of Afghanistan and are living in the US. Even though they’re safe now, they remain in legal limbo. Still, they’re trying to learn English and pursue their education in the US.

High-risk missions

When A. joined the special forces, her parents had a hard time accepting her job, she said. She’d left university partway through a degree in engineering to pursue a military career, and they worried about her.

Just before Kabul fell last year, A. was on high-risk night missions with joint US and Afghan special forces. That meant dropping from helicopters into rough, remote terrain, questioning Taliban fighters and others thought to be connected to them. They were there gathering intel, asking about explosives or other weapons that may be hidden.

“I was in love with my job,” she said. “Wearing body armor, putting the helmet on and taking my gun to go find the enemy … taking care of people and helping people, it made me feel very strong.”

A. was doing work that few expected or accepted from Afghan women. But she saw it as a way to help her country.

As women, the Female Tactical Platoon members fulfilled a role that Afghan and American male soldiers culturally could not — interview women and children, usually wives, daughters or other family members of suspected Taliban fighters.

But it’s this work that put her and the other FTPs in danger when the Taliban came into power.

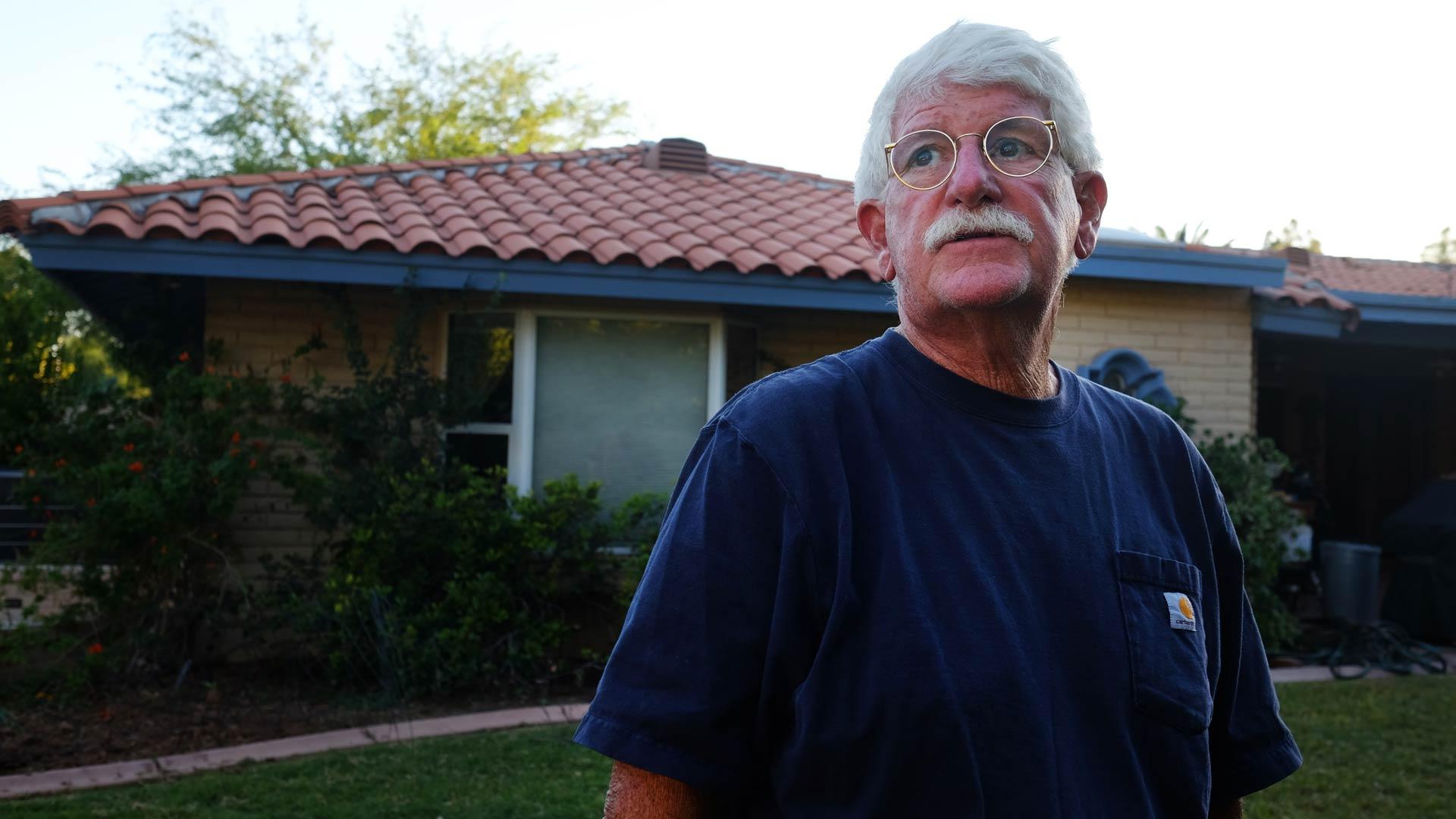

“We assumed that the FTPs would be part of the operation to evacuate,” said Bill Richardson, a US Marine veteran and retired police detective in Phoenix. “But then, we discovered that they were not part of the discussion, there was no mention of them, they weren’t on anybody’s radar.”

Richardson’s daughter, who is in the US Army and worked with A. in Afghanistan, brought their predicament to his attention. Richardson wound up helping A. and other platoon members to leave the country.

One platoon member was killed before she could evacuate. But Richardson and an ad hoc group of other veterans, lawmakers and active duty soldiers managed to get the 39 others out safely last year — across the US.

“A lot of this boiled down to friendships that people had, relationships through serving together friends of friends,” Richardson said. “Or in my case, friends of friends of friends, or calling people cold and saying, ‘Will you please help?’”

But, like thousands of their compatriots, the Afghan women are also stuck — they’re here on temporary immigration status with no clear path to citizenship. Since they were part of the Afghan army, they also can’t apply for the special visas afforded to Afghans who worked for the US. A bill called the Afghan Adjustment Act could change that, but it’s stalled in Congress.

That means aspirations they have with careers and higher education are much more difficult.

A. wants to join the US military and fly helicopters. But despite looking for months, A. doesn’t have a job right now.

“My parents … always say, ‘You have to continue your education, you have to focus on your education, that’s OK we don’t need money,’” she said. “But I don’t feel good because the people in Afghanistan are not in a good situation. And I know they need money because we are not a small family.”

Richardson said this is a persistent issue that many of the former soldiers face, and it’s hard not to think there’s some bias involved — because they’re Afghans, new to the US, or just because they’re different.

“I think the political climate has created an environment where, you know, people want to blame, and they’re not accepting of someone or something that’s different,” he said.

Hurdles to starting over in the US

English proficiency is the first hurdle that the Afghan soldiers have to clear. A. stopped her English studies at Arizona State University earlier this year. Funding got tight, and she said that news from Afghanistan consumed her focus.

It was also difficult to make the transition from soldier to civilian, something Rebekah Edmondson said that she knows a lot about. She’s a US Army Special Forces veteran who served four tours in Afghanistan alongside the Afghan women’s platoon.

“You know, the fact that they went from repelling out of helicopters under night vision, conducting these very high-profile operations,” she said. “Now, they’re here, labeled as refugees in a country that’s not always incredibly welcoming.”

Edmondson trained the first Afghan women’s platoon more than 10 years ago. She said that long before US troops left Afghanistan, Edmondson began to worry that one day, these women would need to leave their country.

She started trying to set up educational opportunities for them in the US, talking with universities about how they could enroll in classes and master’s programs.

“But unfortunately, you know, just with the infrastructure of that country and not having WiFi that was reliable and different things, there were opportunities present, but they weren’t able to take advantage of them,” she said.

She said that’s changing now that the women are in the US. She’s helping to fund online English classes and other training for the platoon members, one of a few women veterans hired by the Pentagon Federal Credit Union to help in that effort.

She said that she tries to see it as a silver lining. But she knows things won’t happen overnight. Like A., many of the women still have family struggling in Afghanistan.

“And so it’s, it’s very, very difficult to expect somebody that’s going through all this mental, emotional anguish to thrive immediately,” she said. “Even if they do get connected to a job and have all these resources, the majority of them are really struggling with that fact.”

Inside her Tempe apartment, A. has a collection of framed photos of her family and work from back home.

The images are tucked away inside a plastic sleeve in A.’s closet, along with a neatly folded Afghan flag. She said that having them out just brings a rush of painful memories.

“My job was taking care of the people, and work[ing] for my country, and help[ing] my country, and unfortunately, when I think about it, it makes me very sad and very angry, because I cannot do anything for the people of Afghanistan, especially the women,” she said.

Still, she said that she’s moving forward. She’ll restart English classes next year. And she wants to get her pilot’s license one day — it’s a new dream that feels close to the work she once loved.

An earlier version of this story was originally published by KJZZ.