How ethnic and religious divides in Afghanistan are contributing to violence against minorities

Close to a hundred Afghan Shiite Muslims were killed in attacks on mosques in October 2021.

One such attack took place on Oct. 15, when a group of suicide bombers detonated explosives at a mosque in Kandahar. Just over a week before that, at least 46 people were killed in another suicide bomber attack in northern Afghanistan. The Islamic State group claimed responsibility for both attacks.

Ethnicity and religion are key to understanding the politics and conflicts of today’s Afghanistan. My research on Afghan affairs can explain how they have created fault lines that have influenced Afghanistan’s politics since 1978.

Afghanistan’s four largest ethnic groups

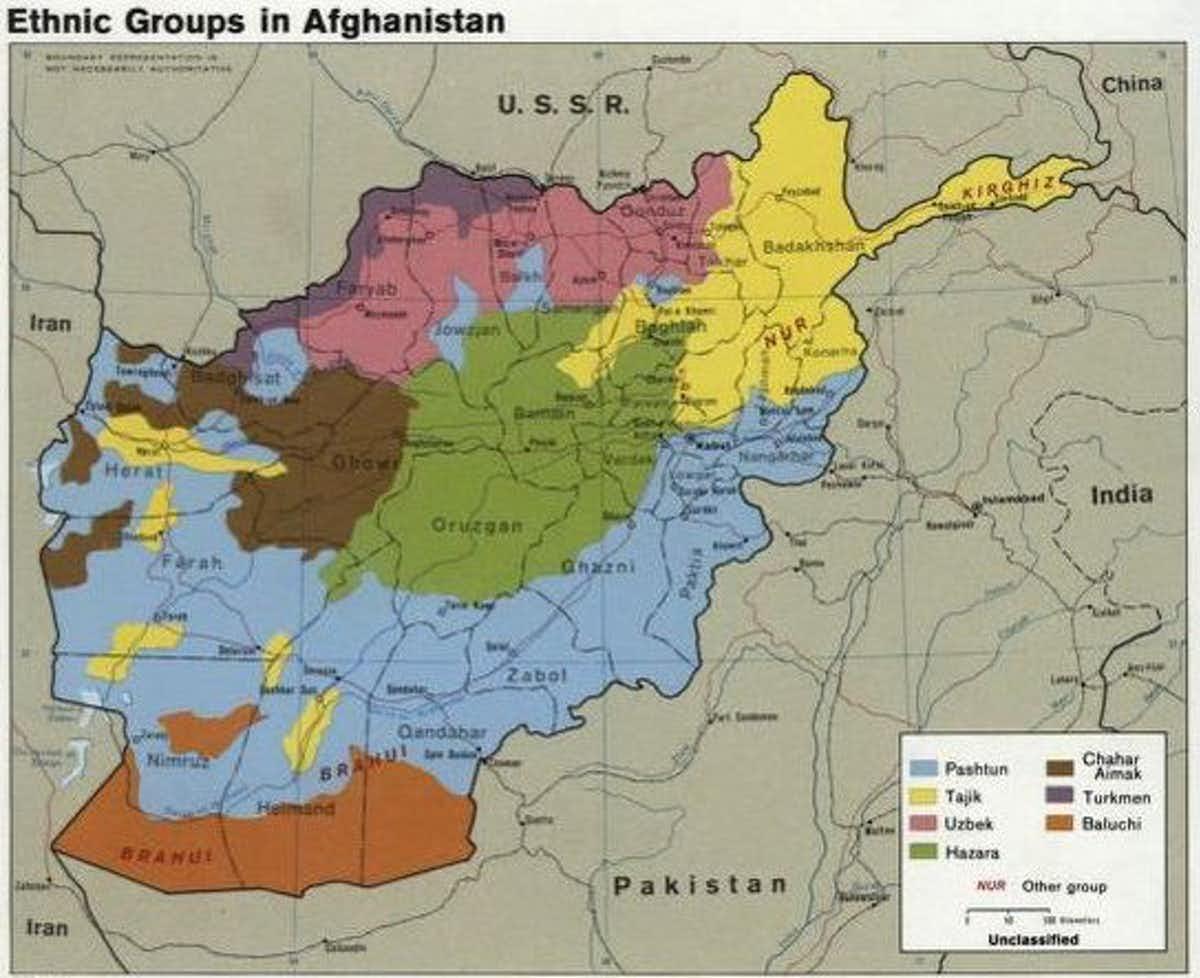

The largest ethnic group in Afghanistan, estimated at around 45% of the population and mostly concentrated in the south and east of the country, are the Sunni Muslim Pashtun.

The Pashtun population is split in half by the border between Pakistan and Afghanistan, the Durand Line, and has a long history of challenging state authority and the legitimacy of official borders in both countries. Until recently, when Pakistan built a fence on the border, Pashtun tribesmen and fighters crossed the border as if it did not exist.

The Pashtun are often characterized as being fiercely independent and protective of their land, honor, traditions and faith. The first time Pashtun fighters defeated an invading superpower was when they destroyed a British army sent to colonize Afghanistan in what is known as the First Anglo-Afghan War, which lasted from 1838 to 1942.

The Pashtun tribes’ and clans’ martial prowess makes them very influential in the politics of Afghanistan. Except for two short-lived exceptions, in 1929 and between 1992 and 1994, only Pashtun leaders have ruled Afghanistan since 1750.

The second-largest ethnic group in Afghanistan are the Tajiks, a term that refers to ethnic Tajiks as well as to other Sunni Muslim Persian speakers. The Tajiks, who constitute some 30% of the Afghan population and are mostly concentrated in the northeast and west, have generally been accepted by Pashtuns as part of the fabric of life in Afghanistan, perhaps because of their common adherence to Sunni Islam.

The third-largest Sunni Muslim group are the Uzbeks and the closely related Turkmen in the north of the country, who form around 10% of the population.

The Hazara — around 15% of the Afghan population — traditionally lived in the rough mountainous terrain in the center of Afghanistan, an area in which they historically sought shelter from Pashtun tribesmen who disapproved of their adherence to the Shiite sect of Islam. The Hazara have historically been some of the poorest and most marginalized people in Afghanistan.

Communist government and Soviet occupation

Most Afghans hardly reacted when a faction of Afghanistan’s communist party took power in April 1978, because the Afghan government had traditionally played a very limited role outside of the larger cities.

They did, however, rise in impromptu revolts when the communists sent their activists to conservative villages to teach Afghan children Marxist dogma. When the Soviets invaded in 1979, resistance spread to much of Afghanistan. Mujahideen — the Muslim warriors defending their land — from all ethnic groups played a role in resisting the Soviet military.

Later, a brutish Uzbek communist militia leader named Abdul Rashid Dostum eliminated most Uzbek Mujahideen, and most Hazara Mujahideen parties made a tacit agreement with the Soviets to reduce hostilities. Most Pashtuns and Tajiks, however, continued to resist until the Soviet withdrawal and the collapse of the Soviet-backed regime in Kabul.

The Soviets promoted minority interests and gender equality in areas of Afghanistan they controlled, which led the larger cities they controlled to evolve culturally to a point that made city life unrecognizably alien to many rural Afghans.

The withdrawal of the Soviet Red Army in February 1989 led to the cessation of US aid to the Mujahideen parties, which turned Mujahideen field commanders, whose loyalty to party leaders was based on their ability to distribute financial and military resources, into militarized independent local leaders. Similarly, the regime’s militias and units also became independent after its collapse in April 1992.

Afghanistan, particularly the Pashtun areas, became fragmented, with hundreds of local leaders and warlords fighting over territory, drug production, smuggling routes and populations to tax. While many local leaders cared about the welfare of their kith and kin, some were warlords who abused fellow Afghans.

The first Taliban era

In 1994, a group of previous Pashtun Mujahideen formed the Taliban and managed to control most of Afghanistan, including Kabul, by the time the US invaded in late 2001.

The Taliban’s rise was fueled by rural Pashtun support for its agenda of ending warlord-generated insecurity, bringing back Pashtun prominence and re-creating traditional Pashtun village life — as they imagined it to have been. The Taliban’s conservative views reflected the values of a large section of the public they governed in the south and east of the country.

The conservative rural Taliban, traumatized by decades of war, encountered an alien cultural environment when they took over Kabul. They reacted forcefully, limited urban women’s access to education and labor and imposed strict limitations on dress, appearance and public behavior.

Afghans in urban areas, particularly women, and members of Afghan minorities did not by and large share the parochial Taliban understanding of their common faith. They were undermined, threatened or punished when they attempted to challenge Taliban restrictions. The Shiite Hazara, in particular, were subjected to brutal retaliatory attacks when they resisted Taliban rule.

The US occupation

The US military invaded Afghanistan and allied with minority local leaders and some Pashtun warlords to oust the Taliban. These warlords ended up filling most key posts in the regime the US-led coalition established in Kabul.

For warlords from all backgrounds, it appeared to be a golden age. The rest of the Afghan population, even more so in Pashtun areas than in others, went back to suffering from warlords’ predatory behavior.

In 2004, three years after the US occupation began, the mostly Pashtun Taliban reorganized as an insurgent force to fight the US-led occupation and the regime it established in Afghanistan.

Enterprising urban youths, including women, from historically disadvantaged minorities, particularly the Shiite Hazara, took advantage of aid, education programs and foreign-driven employment opportunities to advance. In contrast, the rural Pashtun, who suffered the brunt of the warfare between the Taliban and US-led coalition, were set back economically and hardly benefited from investments in health and education.

One of the byproducts of the US occupation of Afghanistan was the development of a local branch of the Islamic State, the Islamic State-Khorasan (an Arabic name for the region). The organization was formed by defectors from the Taliban who felt that their leadership was too soft on the Americans. This group has engaged in attacks on Shiite civilians, whom it considers to be heretics and agents of Shiite Iran. It was responsible for attacks on US troops such as the August 2021 attack on the Kabul airport. It is also antagonistic toward the Taliban.

The return of Taliban

The return of the Taliban to Kabul after the withdrawal of US troops in August 2021 is a return to a rural Pashtun order. Most Taliban leaders are rural Pashtuns who received their education in conservative madrassas in Afghanistan or Pashtun areas of Pakistan. Only three of the 24 members of the Taliban interim government are not Pashtuns — they are Tajiks.

And the Taliban are running the country the way they imagine life in Pashtun villages used to be before Afghanistan sank into perpetual war in 1979. The Taliban movement caters to the sensibilities of conservative rural Pashtun Muslims. Their understanding of Islam is not necessarily shared by other Afghans, religious as they may be.

In the meantime, the Islamic State group is conducting massive terrorist attacks on Shiite mosques, a tactic that originated with the Iraqi branch of the organization. One aim of the Islamic State’s attacks, I believe, is to drive recruitment that has weakened over the past years by appealing to anti-Shiite sentiment among the Pashtun, particularly after the US withdrawal and Taliban successes on the battlefield.![]() Abdulkader Sinno is an associate professor of political science and Middle Eastern Studies at Indiana University. This article is republished from The Conversation a nonprofit, independent news organization dedicated to unlocking the knowledge of experts for the public good.

Abdulkader Sinno is an associate professor of political science and Middle Eastern Studies at Indiana University. This article is republished from The Conversation a nonprofit, independent news organization dedicated to unlocking the knowledge of experts for the public good.