As a barista at one of Colombia’s leading coffee chains, Sandra Salazar spends a lot of time interacting with customers.

So, the 28-year-old felt relieved this month when her company, Juan Valdez coffee chain, signed her up for the first dose of Sinovac, a coronavirus vaccine manufactured in China.

Related: Colombia loosens COVID restrictions to save the economy

“I’m very happy. … I’ve wanted to do this for a long time, but under the government’s program, I would’ve had to wait until October or November.”

“I’m very happy,” she said after preparing a medium latte with skim milk. “I’ve wanted to do this for a long time, but under the government’s program I would’ve had to wait until October or November.”

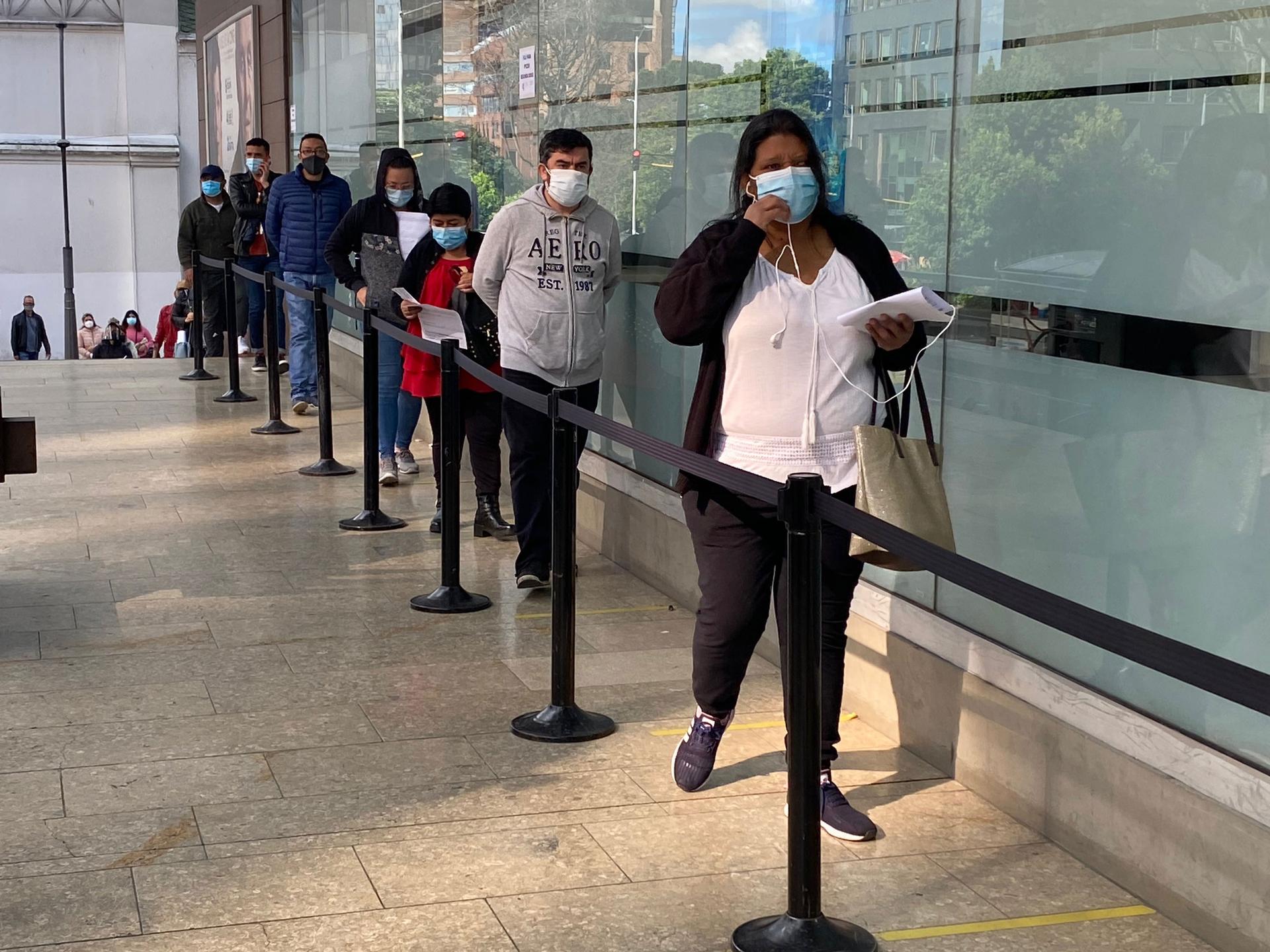

In Colombia, only 15% of the population of 50 million has been fully vaccinated. When shots arrive, long lines are still common.

To protect workers, some companies have begun to import shots through a privately funded vaccination drive expected to cover more than 1 million people in the following month.

Officials hope that the privately funded campaign will help to speed up the vaccination rollout by opening up new channels to distribute the COVID-19 shot.

Related: Amid pandemic, Venezuelans hit the road again in search of work

But some public health experts say the move puts the needs of companies above scientific criteria commonly used to decide who gets vaccinated first. Some also believe that the scheme creates a VIP line for companies and their employees — while others wait.

“When vaccines are scarce, the best policy is to direct them toward population groups that are most likely to get sick.”

“When vaccines are scarce, the best policy is to direct them toward population groups that are most likely to get sick,” said Dr. Herman Bayona, director of Bogotá’s Medical College.

“A better idea would have been for companies to donate funds to the government so that it can improve its own vaccination drive, which is distributing shots more fairly,” said Bayona, who is also a spokesman for the Alliance for Health and Life, a public health expert group that has voiced criticism of the Colombian government’s approach to the pandemic.

Only people over 40, and those with serious illnesses, are currently eligible for vaccines from the Colombian government, because shots are in such limited supply. But companies that import their own vaccines are free to choose which employees get them first, regardless of their age or their level of exposure to the virus.

Colombia’s government is requiring companies to provide purchased vaccines free of charge and ensure enough shots for all staff members. And the government brokered their procurement to stop companies from competing with the public sector for vaccines.

Related: Coronavirus spread threatens Colombia’s Amazonian Indigenous communities

At a recent event where officials announced the arrival of the first batch of vaccines for companies, President Iván Duque said that other countries in Latin America are also inquiring about Colombia’s privately funded vaccination drive.

Indonesia has a similar program, and companies in India and Pakistan have also been given the green light by their governments to import vaccines.

“This is a great example of what we can achieve when the private sector and the public sector work together,” Duque said.

But Colombia’s privately funded program leaves out millions of young people who are still not eligible for the government’s vaccination program, and who also don’t work for companies that provide shots.

Scissors barbershop in Bogotá mostly employs workers in their 30s, who all protect themselves with masks while in constant contact with customers.

Dennis Revilla, a barber, said that everyone here works for commissions, so he doubts the shop’s owner will get them vaccines.

“We’re still waiting. … Hopefully, God will listen to our prayers and keep us healthy until it’s our turn.”

“We’re still waiting,” he said. “Hopefully, God will listen to our prayers and keep us healthy until it’s our turn.”

Despite inequalities, companies argue that their vaccination drive will eventually benefit everyone.

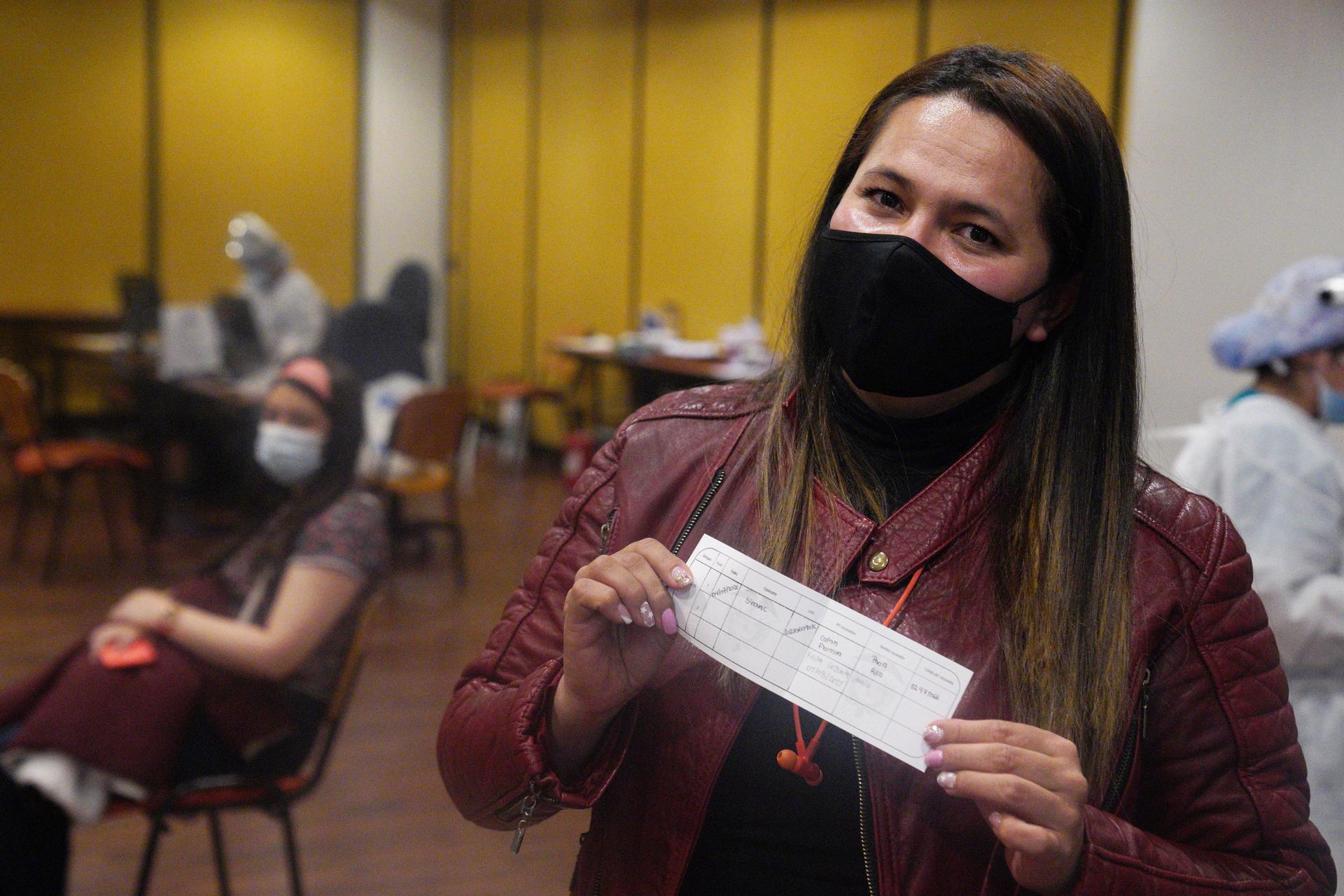

Sandra Romero works at Evertec, a digital payments company that bought vaccines for all of its workers. Many of Evertec’s employees are in their 30s, as well.

“If companies are vaccinating their staff in a big way, it will be easier for vaccines purchased by the government to go straight to vulnerable communities. … Perhaps they will even have enough for younger people.”

“If companies are vaccinating their staff in a big way, it will be easier for vaccines purchased by the government to go straight to vulnerable communities,” Romero said. “Perhaps they will even have enough for younger people.”

Colombia’s private sector currently holds 2.5 million Sinovac vaccines on reserve, purchased by the Colombian government from China. Government officials handed over the vaccines to the group of companies that agreed to pay for, and distribute, the shots.

Claudia Vaca, an epidemiologist at Bogotá’s National University, said that, in exchange for brokering vaccines, Colombia’s government could have asked companies to do more for the public vaccination program.

“For every vaccine purchased by a company, the government could have asked them to purchase another vaccine for somebody who is unemployed, or who works in the informal economy. … A big opportunity was missed.”

“For every vaccine purchased by a company, the government could have asked them to purchase another vaccine for somebody who is unemployed, or who works in the informal economy,” she said. “A big opportunity was missed.”

Despite these criticisms, companies press on with their vaccination campaign, as thousands of workers get their first dose.

It may not be the most equitable way to distribute vaccines. But for countries that continue to face vaccine scarcity, privately funded vaccination drives can expedite the process.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?