Montenegro was a success story in troubled Balkan region – now its democracy is in danger

Tiny Montenegro has long been different from its neighbors in the former Yugoslavia.

After a decade of bloody civil wars that included ethnic cleansing and acts of genocide, Yugoslavia in the 1990s split violently along ethnic lines into six different independent republics. But Montenegro escaped the worst of the war and for years remained with Serbia — its dominant, Russian-allied neighbor — as part of the “rump Yugoslavia.”

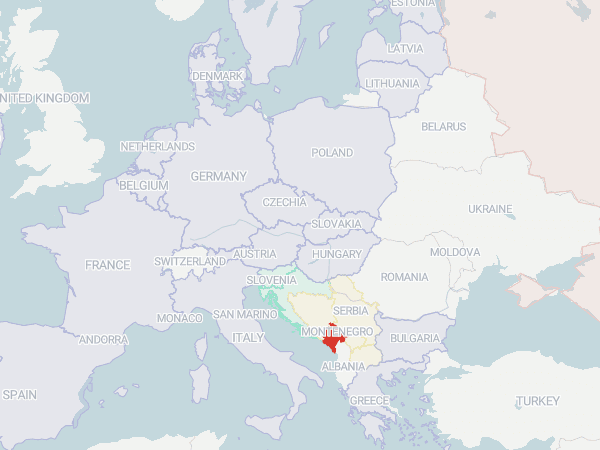

In 2006, Montenegrins voted for independence and separated from Serbia peacefully. Montenegro became a stable and inclusive democracy. It is a mountainous, postage-stamp-sized country of 640,000 on the eastern Adriatic Sea.

Rather than maintain the Slavic ethnic identity of Serbia, Montenegro made room for all kinds of people. It was home to Montenegrins — who are Orthodox, Muslim, Catholic and atheist — yes, but also Bosniaks, Albanians, Roman-Catholic Croats and Serbs. Montenegro also has a Jewish community.

Montenegro’s post-independence leaders in the socialist party worked to build a broad civil society that recognized the many identities of its citizens. Many refugees from the Balkan wars sought safety in Montenegro.

Its political system favored neither majorities nor minorities, a value system inherited from Yugoslavia. In 2017, Montenegro joined NATO, the transatlantic security alliance, against Russia’s wishes. It wants to join the European Union.

Montenegro’s Balkan success story — and its very national identity — is now in danger after a right-wing coalition aligned with Serbia and Russia took power in December.

A language grows and struggles

A fight over the Montenegrin language is symbolic of the broader political fight playing out in Montenegro.

All the former Yugoslavian republics — Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Montenegro and Serbia — share a mutually intelligible language, previously called Serbo-Croatian. The differences among them are comparable to the varieties of English spoken by Americans, Australians, British and South Africans.

Since Yugoslavia broke up, each new Balkan nation has used language to create a common political and cultural identity for itself, establishing each language with its distinctive style and standardizing its usage.

As my research and others’ show, some were more successful in that effort than others. Bosnian, Croatian and Serbian are now well established as national languages, used in schools, the press, business and government.

Montenegrin, however, remains contested.

It is embraced by citizens who stand for an inclusive, multi-ethnic Montenegrin society. But those who view Montenegro as fundamentally an extension of the Serbian state consider Montenegrin merely a dialect of Serbian. According to a leader of the Serbian Orthodox Church, “Montenegrin does not exist.”

Montenegro’s new coalition government seems to side with the Serbs on the language question.

In March the new minister of education, science, culture and sports, Vesna Bratić — who identifies as a Serbian nationalist — threatened to close the Faculty of Montenegrin Language and Literature in the old royal capital of Cetinje and has blocked its funding since January. The institute has led efforts to standardize the Montenegrin language and foster scholarship about Montenegrin literature and culture.

In a young country still forging its national identity, erasing the Montenegrin language that has bound its people together is akin to eliminating the Montenegrin identity.

A nation falls apart

Multi-ethnic Montenegro has so far achieved stability through a balancing act that recalled how Yugoslavian premiere Josip Broz Tito ran multi-ethnic Yugoslavia for much of the last century.

Yugoslavia, founded in 1918, was dominated by Slavic-speaking Serbs, Croats and Slovenes but was home to many Hungarians and Albanians, among other non-Slavic minorities. It was also divided religiously, between Roman Catholicism — the faith of Slovenians and Croatians — and the Eastern Orthodox Christianity of Serbians, Montenegrins and Macedonians.

After the Second World War, Marshal Tito and his Partisans — having driven out Nazi occupiers — led Yugoslavia under socialist rule. For four decades, Tito maintained order and quelled rivalry within Yugoslavia with an iron fist and by careful balancing of conflicting claims for cultural dominance.

From the Yugoslavian capital, Belgrade, Tito promoted a one-party system and ideology fostering “brotherhood and unity” among Yugoslavia’s many disparate traditions and communities.

That delicate balance broke down after Tito’s death in 1980.

Wars erupted in Yugoslavia along national, ethnic and religious lines. Serbian and Croatian paramilitaries seeking to carve out ethnically pure states carried out ethnic cleansing operations against their rivals in each others’ territories and elsewhere. Bosnia and Herzegovina — fragmented among Catholics, Muslims and Eastern Orthodox — witnessed the gravest atrocities.

History repeats itself

Montenegro now seems to be at risk of a similar unraveling with its long-ruling Democratic Party of Socialists out of power. While rhetorically supporting Montenegro’s NATO and EU membership, Montenegro’s new political leadership is ideologically aligned with Serbia and Russia.

Many Montenegrins are appalled by their young democracy’s unexpected twist of fate. They fear Serbian cultural hegemony will negate their progress in nation-building and move Montenegro away from European values — and toward Russia.

Russian President Vladimir Putin is watching the struggle over Montenegro’s future closely. Russia has traditional cultural and religious ties to Montenegro, and having Montenegro in Putin’s “portfolio” would give Russia access to a Mediterranean port.

Some Montenegrins even worry that violent ethnic conflict could begin again anew. For them, the Balkan wars are still a fresh memory. And they’ve seen several democracies in Eastern Europe – Poland and Hungary chief among them — come under autocratic rule.

The West learned the hard way 25 years ago that conflict in the former Balkans can end in tragedy. Will this history repeat itself in Montenegro?![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit news organization dedicated to unlocking ideas from academia, under a Creative Commons license.