Whenever there’s an analysis or discussion about how much people know about the Holocaust, the focus is often on what they don’t know.

For instance, a 2018 survey of 1,350 people age 18 and older found that 11% of US adults and 22% of millennials had not heard of — or were not sure if they had heard of — the Holocaust.

Almost half of US adults — 45% — and millennials — 49% — could not name one concentration camp or ghetto that was established in Europe during the Holocaust, the survey found.

The survey also showed how there’s an overwhelming lack of personal connections to the Holocaust. Most Americans — 80% — had never visited a Holocaust museum and two-thirds — 66% — did not know, or know of, a Holocaust survivor. A significant majority of American adults believed that fewer people care about the Holocaust today than before.

As troublesome as these statistics may be in terms of what they show about how little people know about the Holocaust, there’s another aspect to Holocaust knowledge that often goes overlooked.

And that is, at a time when the Holocaust has “taken on a virtual dimension” and images from the horrific era are prevalent online, there is now a risk of what author Gavriel Rosenberg refers to as the “normalization” of the Nazi past in contemporary culture.

Desensitization

As the number of Holocaust survivors continues to dwindle, today’s students may be more apt to find a Hitler meme online before they discover testimonies of Holocaust survivors.

Rosenberg argues that this normalization of the Holocaust will downplay its horrific nature. In some cases, people have seemingly taken to celebrating the Holocaust. For instance, at the Jan. 6 attack on the US Capitol, one participant wore a “Camp Auschwitz” hoodie — a macabre acknowledgment of the most infamous of the Nazi concentration and death camps.

At a December 2020 protest in Washington, DC, against the election of then-President-elect Joe Biden, a member of the Proud Boys — a pro-Trump organization designated as a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center — wore a shirt emblazoned with “6MWE.” The slogan stands for “6 million wasn’t enough,” in reference to the 6 million Jews who were killed in the Holocaust.

Making history accessible

Since the COVID-19 pandemic swept across the globe in early 2020, teachers have adapted instruction to make use of existing and emerging technologies. In line with the purpose of International Holocaust Remembrance Day on Jan. 27, digital tools are offering educators new innovative ways to engage with Holocaust history

The internet has made survivor testimonies easily accessible. Social media platforms have made learning about the Holocaust easier for younger people.

A popular Instagram account appeared in 2019 that features excerpts from the journal of Eva Heyman, a 14-year-old girl from Poland who was murdered in a death camp.

In recent years, virtual reality been used as a tool for Holocaust education and memorialization. For instance, the University of Southern California’s USC Shoah Foundation has launched a project to develop interactive holograms of Holocaust survivors. The first time the exhibit was displayed publicly was at The Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center in 2015.

Criticisms from scholars

However, some scholars challenge the use of virtual reality when it comes to the Holocaust. One concern is the risk that people who go through a virtual reality simulation will incorrectly feel that they now know what the historical event itself was like, thereby trivializing it.

I myself am leading an interdisciplinary team at Rowan University in New Jersey to develop a virtual reality teaching tool about the Warsaw Ghetto, the largest ghetto established by the Nazis during the Holocaust — holding more than 400,000 Jews within an area of 1.3 square miles, with an average of 7.2 persons per room.

This project, still in its pilot stage, uses primary-source documents and photographs from the Oneg Shabbat Archive to recreate spaces within the ghetto. Users will be able to explore re-created spaces, examine primary sources, ask questions about photographs and explore a variety of themes.

To better develop The Warsaw Ghetto Teaching and Learning Project, and as author of a chapter in a forthcoming book, “Teaching and Learning Through the Holocaust,” I have examined many digital tools that can be used to teach about the Holocaust, especially in middle and high schools.

Here are five websites that I consider to be the most interesting.

1. The life of Bebe Epstein

This first foray into digital education from YIVO, The Institute for Jewish Research, tells the life story of one young girl, who was born in Vilna, Poland, from before the Holocaust through her immigration to the United States. A staggering amount of information can be found in this digital tool, which consists of 10 self-guided “chapters” containing the story of Bebe Epstein, artifacts and maps.

2. ‘History unfolded’: US newspapers and the Holocaust

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum has a number of excellent online exhibits that can be used for teaching and learning, but “History Unfolded” fills a gap: This website aims to show what Americans knew about the Holocaust, and when they knew it, by using articles from US newspapers published during the 1930s and 1940s. Users can explore by event.

For example, they can search for Kristallnacht, a series of violent massacres carried out against Jews in Germany, often referred to as the “Night of Broken Glass.” Or they can search for information about the USS St. Louis, a ship that brought 900 Jews to Cuba and then the United States, where they were turned away. Upon being returned to Europe, almost all aboard were murdered in death camps. Visitors can also search their local newspapers from the period.

3. In Mrs. Goldberg’s Kitchen

This augmented reality experience is a part of a larger project about Lodz, Poland, during the period between World War I and World War II, created by Halina Goldberg, a musicology professor at Indiana University Bloomington. This interactive exhibit allows users to explore space in the Jewish Quarter of prewar Lodz, understanding what daily life was like for so many Jews before they were displaced and murdered during the Holocaust.

4. Anne Frank House: The Secret Annex

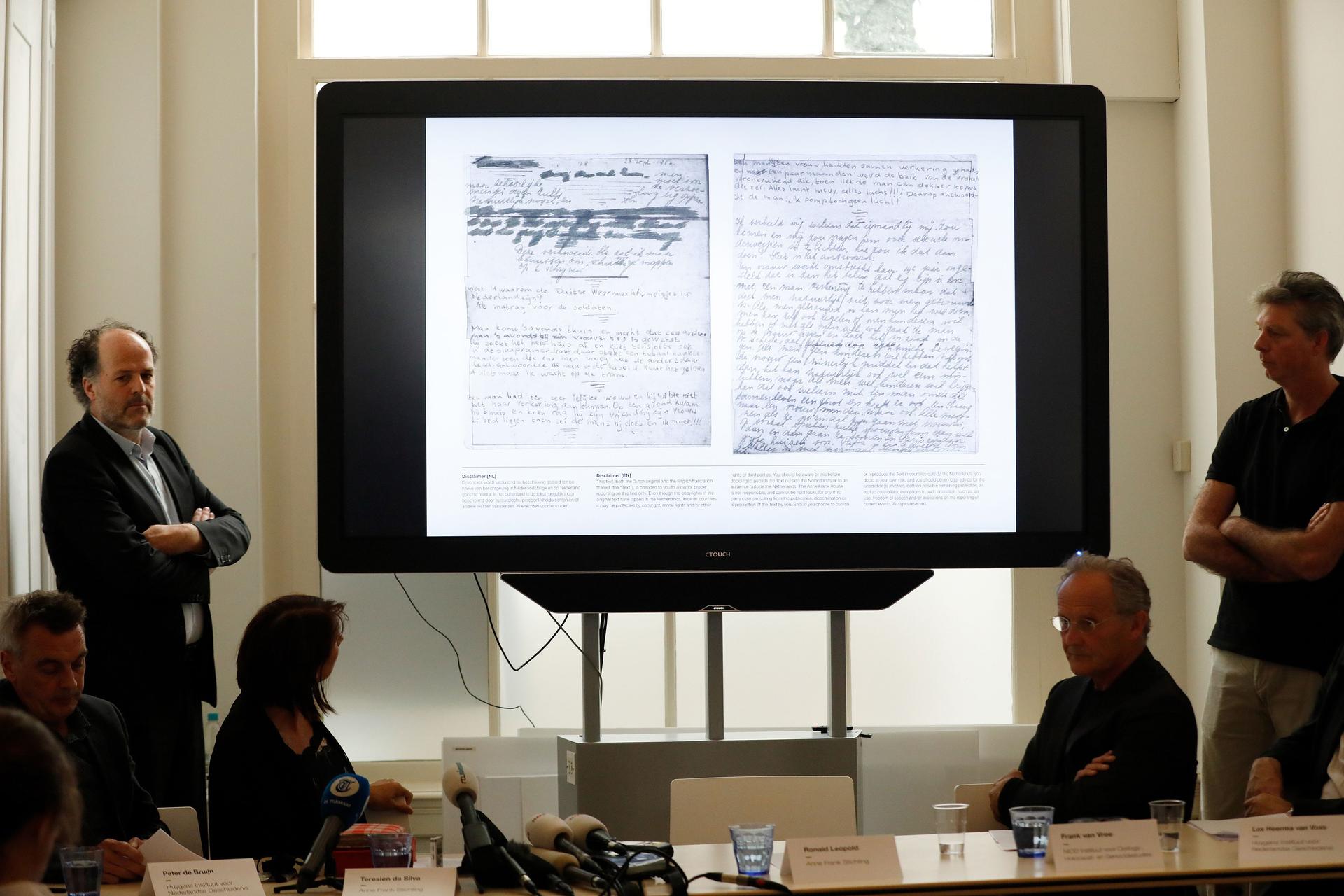

Anne Frank’s diary is one of the best-known primary sources to have survived the Holocaust. The annex where Anne and her family hid during the war still exists in the Netherlands and is a popular site for tourists. For those who are unable to visit the site — and for everyone during the COVID-19 pandemic — the augmented-reality site created by the Anne Frank Museum is an impressive alternative. Users are able to explore the space, examine documents and look at photos.

5. Virtual Tour of the Auschwitz Memorial

Auschwitz is the best-known concentration camp built with the express purpose of murdering Jews and other victims of the Holocaust. While the memorial and museum remain closed because of COVID-19, the virtual tour presents what the memorial website describes as “authentic sites and buildings of the former German Nazi concentration and extermination camp, complete with historical descriptions, dozens of witness accounts, archival documents and photographs, artworks created by the prisoners, and objects related to the history of the camp.” Each location allows users to access additional information, view primary sources, and listen to survivor testimony.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit news organization dedicated to unlocking ideas from academia, under a Creative Commons license.