The Irish govt and Catholic Church apologized for abusive mother-and-baby homes. Survivors say it’s not enough.

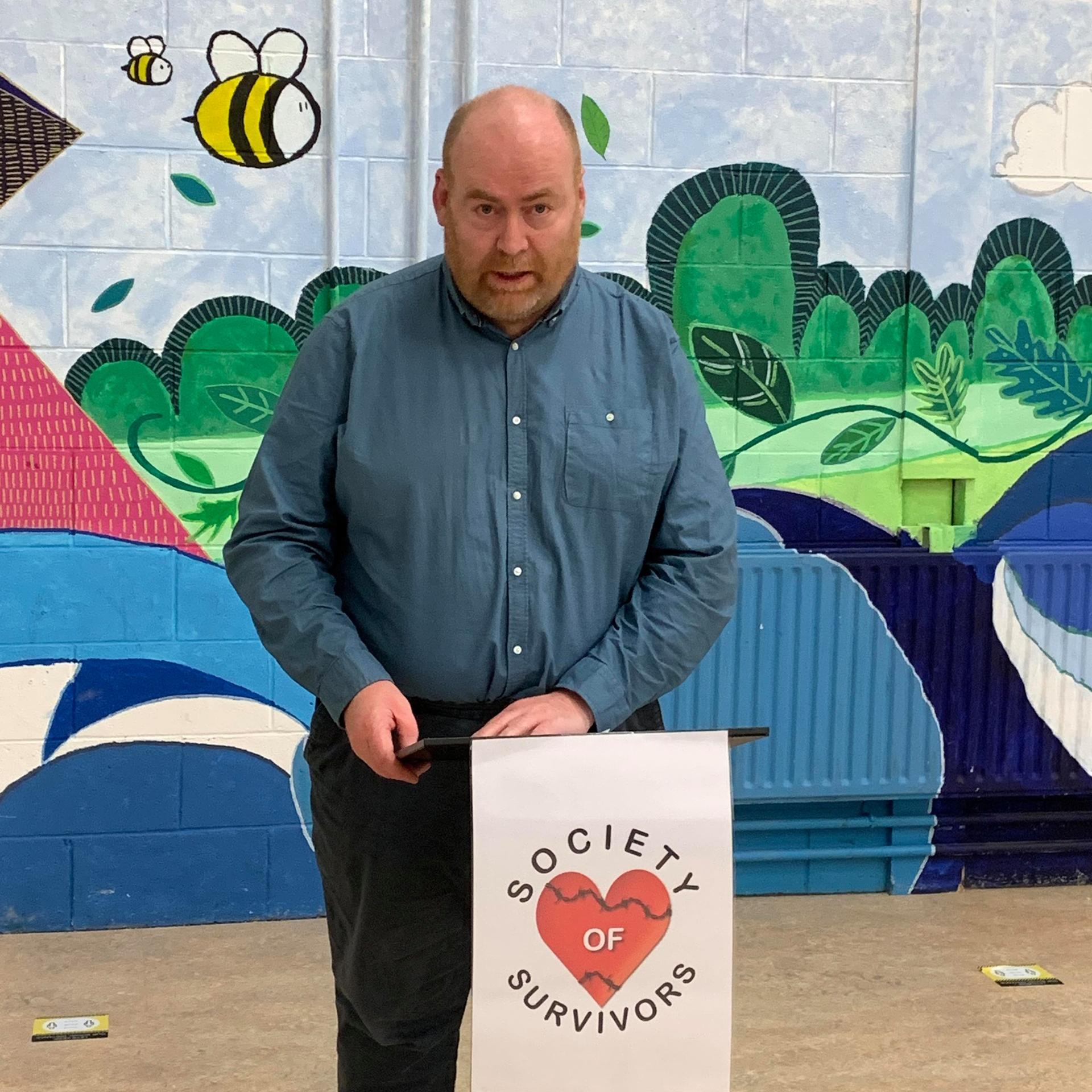

Francis Timmons was born in 1971, at Madonna House, a state-run home for unwed mothers and their children, in Dublin. Timmons was only 4 when he left the home, but still has painful memories of his time there.

“I remember a very harsh place; I have memories of an awful lot of upset, tears and crying and just generally, not being happy.”

“I remember a very harsh place; I have memories of an awful lot of upset, tears and crying and just generally, not being happy,” he said.

Timmons’ late mother, then a 21-year-old unmarried woman, was kept at a separate institution, St Patrick’s in Dublin. She was rarely allowed to see her son. Being a single mother in the 1970s, Timmons says, was probably one of the biggest crimes in Ireland at the time. And the religious order that ran the homes, he adds, made the women feel humiliated about their pregnancies.

Related: Activists took Irish govt to court over national climate plan and won

Like many children in the institutions, Timmons was included in two vaccine trials as a toddler, without his mother’s consent. At the age of 4, he was sent to live with a foster family but the abuse continued.

Many of the children born in Ireland’s mother-and-baby homes were sent to foster families or put up for adoption often against their mother’s wishes. Some were sent to families abroad, the majority to the US. The story of forced adoptions to the US from Ireland’s mother-and-baby homes featured in the 2013 Oscar-nominated film, “Philomena,” starring Dame Judi Dench.

This week, the Irish prime minister and the Catholic Church apologized for the treatment of women and their children in Ireland’s so-called mother-and-baby homes during much of the 20th century. The apologies follow a five-year investigation that found an “appalling level of infant mortality” in the institutions.

Taoiseach Micheál Martin said the inquiry’s report revealed a “dark, difficult and shameful chapter” in Irish history. But many survivors of the homes that were funded by the Irish state and run mainly by Catholic nuns say apologies are not enough.

The prime minister’s apology comes on the back of a 3,000-page report documenting the cruel conditions in 18 of Ireland’s mother-and-baby homes. Around 56,000 women and 57,000 children were placed or born at the homes from 1922 to 1998.

This week’s report documents harrowing abuse in many of the homes, recording that 9,000 babies died in the institutions, double the national average. The last remaining mother-and-baby home was only closed in 1998.

‘Society was complicit’

In 2011, local historian Catherine Corless began research into the mother-and-baby home in Tuam, County Galway. She discovered that almost 800 babies had died in that mother-and-baby home between the 1920s and the 1960s, but could find no records of where the children had been buried. Corless suspected the children had been buried in unmarked graves on the grounds of the home.

In 2017, an inquiry confirmed Corless’ suspicions, including that some babies had been interred in a disused septic tank. Her findings sparked outrage in Ireland and created international news headlines.

Related: Northern Ireland’s police reform efforts hold lessons for the US

Prime Minister Micheál Martin said the findings depict a shameful image of Ireland.

“It opens a window onto a deeply misogynistic culture in Ireland over several decades with serious and systematic discrimination against women,” he said.

Many countries had mother-and-baby homes but more single mothers were sent to the homes in Ireland than anywhere else. The prime minister said the country had treated women and children “exceptionally badly” and had a “warped attitude to sexuality and intimacy.”

Ireland had to take collective responsibility for what happened, he said: “One hard truth is that all of society was complicit in it.”

Micheál Martin’s comments sparked anger among survivors. Saying society was complicit in what happened, they argue, leaves the Irish state and the church off the hook. The report also points the finger at the unmarried fathers and the women’s families who abandoned them.

But many survivors say it was the overarching influence of the Catholic Church, aided by the state, that left families and the women themselves feeling they had little choice but to turn to the mother-and-baby homes.

The head of the Catholic Church in Ireland, Archbishop Eamon Martin, this week also issued a statement of apology. The archbishop said the church was part of a culture in which people were “frequently stigmatized, judged and rejected.” This report is just the latest in a series of inquiries documenting abuse in institutions managed by religious orders in Ireland.

Michael Kelly, editor of The Irish Catholic newspaper, says the findings have been deeply damaging for the church in Ireland.

“The damage has been immense, the moral credibility of the church in many ways is in tatters in this country.”

“The damage has been immense, the moral credibility of the church in many ways is in tatters in this country,” he said.

Related: Ireland votes to repeal abortion restrictions, but there’s still a lot to talk about

Kelly says the depressing thing for the Catholic Church to realize is that the damage is of its own making. But he says Irish people continue to go to mass every week in greater numbers than most European countries. Many have managed to maintain their faith and separate it from the wrongdoings of the religious institution, he says.

The influence of the Catholic Church in Irish society has dropped dramatically in recent years as evidenced by the country’s legalization of abortion and introduction of gay marriage. The church does continue to run the majority of Irish primary schools, but its influence on political life has been greatly reduced. And Kelly says that’s not a bad thing.

“Because the church, when it’s at its best, should be on the side of the marginalized, not siding with the powerful against the marginalized.”

‘We need to know exactly what happened’

Timmons says his grandparents, whom he got to know later in life, were good people, but the message from the Catholic Church, which held such a powerful influence on Irish society back then, was that his mother had brought shame on the family.

Related: Northern Ireland still divided by peace walls 20 years after conflict

Timmons says the legacy of what happened to him in the early years of his childhood has stayed with him throughout his life. He drank heavily in his 20s and had recurring relationship problems. Today, Timmons is a local councilor in Dublin, and runs a helpline for survivors of the institutions. He says addiction issues and psychological problems are common among those he talks to.

For Timmons, the Commission of Inquiry’s report has been a long time coming. But he’s not convinced it goes far enough.

Timmons’ 3-year-old sister died in a mother-and-baby home, and the family has never received a death certificate or details of where she was buried. Timmons says a criminal investigation is needed to uncover how and why so many children died in these homes.

“Any information in regards to those children dying should go to the courts and should be investigated by the police force in Ireland. We need to know exactly what happened.”

“Any information in regards to those children dying should go to the courts and should be investigated by the police force in Ireland. We need to know exactly what happened.”

The commission’s report makes 53 recommendations including providing compensation to the survivors. Many are now elderly, and Timmons says he wants assurances from the Irish government that they will be looked after in their old age. Above all, he says, he doesn’t want this inquiry to become yet another report that is left to gather dust on the prime minister’s desk.

The World is an independent newsroom. We’re not funded by billionaires; instead, we rely on readers and listeners like you. As a listener, you’re a crucial part of our team and our global community. Your support is vital to running our nonprofit newsroom, and we can’t do this work without you. Will you support The World with a gift today? Donations made between now and Dec. 31 will be matched 1:1. Thanks for investing in our work!