This analysis was featured in Critical State, a weekly newsletter from The World and Inkstick Media. Subscribe here.

Last week, Critical State looked at recent scholarship on how cherry-picked understandings of foreign cultures can shape the politics of international relations. Today, they take a deep dive into the cultural stories countries tell about themselves — and some of the ways it can blind them to their own policy failures.

Related: Misusing culture in international politics: Part I

University of Wisconsin-Madison PhD candidate Anna Meier has a new article out in International Studies Quarterly that examines why the German government is so bad at responding to white supremacist violence. As in many countries, white supremacist attacks in Germany are often presented in the media as turning points, after which nothing — and particularly not government security policy — can be the same. Yet, as is also a common experience, those attacks are almost never turning points. Small policy changes offer the illusion of reform, but underlying conditions remain the same and when a new attack comes, the cycle of shock followed by a lack of reform begins again.

Related: Is there a ‘Nazi emergency’ in the German city of Dresden?

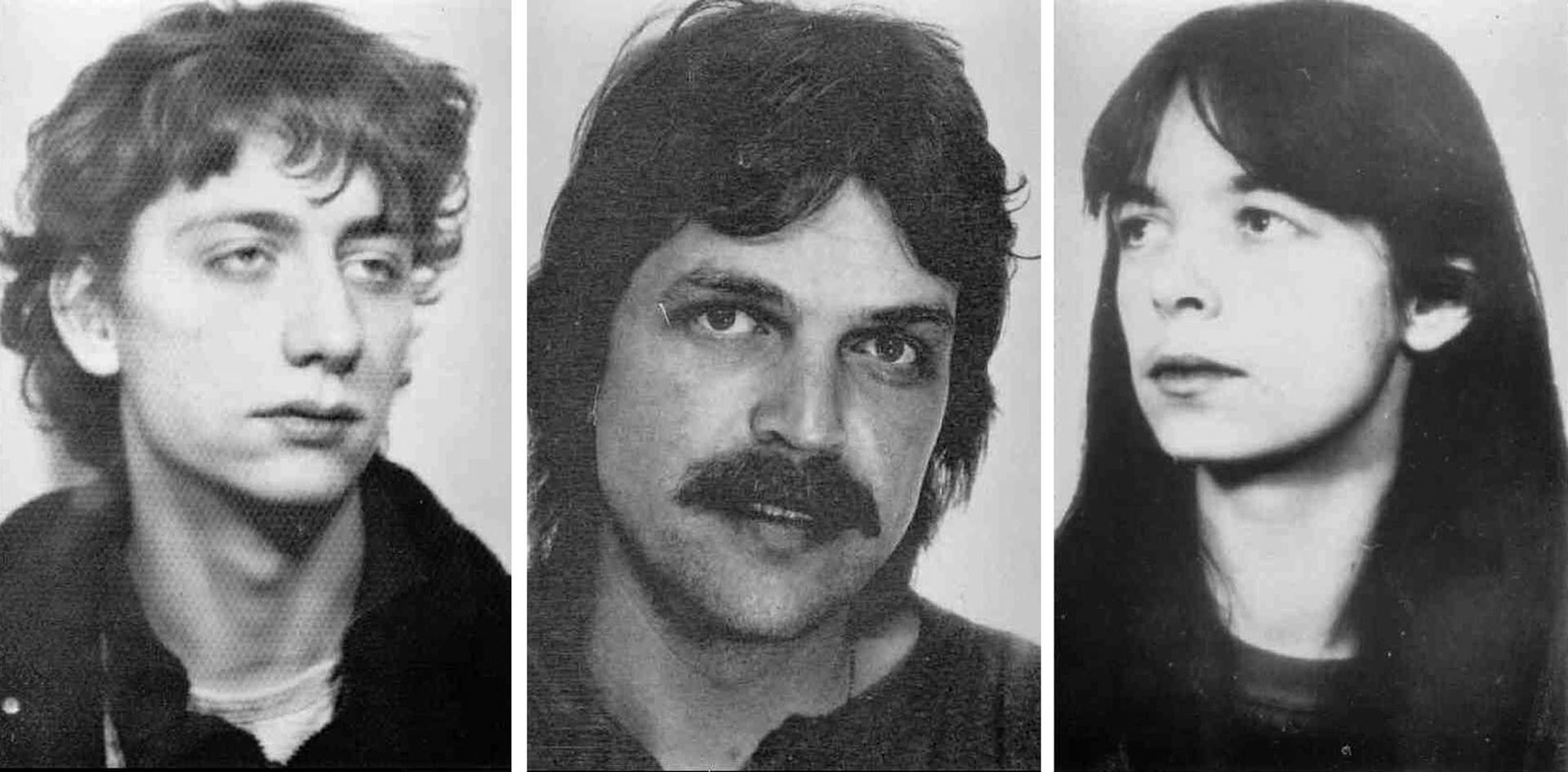

As Meier points out, this lack of response is in sharp contrast to how Germany and other “Western” governments react to other violence that gets classified as “terrorism.” When left-wing militants of the Red Army Faction (RAF) carried out attacks in West Germany in the 1970s, the West German government created a whole new legal structure for counterterrorism for the express purpose of containing the RAF. The new laws targeted the RAF’s modus operandi as an organized group that planned attacks long in advance, threatening stiff sentences for people involved in militant groups of at least three people or who engaged in what the law called “preparatory acts” for attacks.

At the same time that the RAF was promptings such a big response, however, West Germany was also seeing a rise in neo-Nazi violence. Neo-Nazi organizations boasted around 3,000 active members between 1970 and 1972, and in 1971, they killed more people than in any year since the government started keeping track. In that one year, neo-Nazis killed more people than the RAF did in its whole history. Yet the legal response to the neo-Nazi killings was anemic compared to the response to the RAF. As one German security professional Meier spoke to described it, in Germany, “before 9/11, ‘terrorism’ always meant ‘left-wing ’ because of the RAF.”

“The position of white supremacy as a hegemonic component of national identity in Germany means that to seriously reckon with the phenomenon of white supremacist violence would require questioning a system whose existence depends on not being questioned.”

Meier argues that the difference in how the two are treated is rooted in Germany’s cultural understanding of itself. If the thing that differentiates terrorism from other forms of criminal violence is the sense that it threatens a social fabric beyond that of its immediate victims, then it makes sense that violence seeking to upend a social order that sees whiteness as a crucial part of Germanness would be seen as more serious than violence seeking to uphold that order. As Meier writes, “the position of white supremacy as a hegemonic component of national identity in Germany means that to seriously reckon with the phenomenon of white supremacist violence would require questioning a system whose existence depends on not being questioned.”

Related: Artists in Germany fear backlash after far-right party wins big

What’s curious is that, as Meier found in her interviews of German security bureaucrats, many of them find their national double standard about white supremacist violence as ridiculous as she does. One memorably summed up the problem by saying that the German state believes that left-wing and Islamist terrorism “threatens… the foundations of society: property rights, democracy, Christian values, Western values [switches to English and rolls eyes], whatever that means. [switches back to German] This is just my theory, but the victims [of far-right attacks] were ‘only’ migrants.”

Yet those same bureaucrats despair of fixing the double standard because of a lack of public pressure to do so. The national discourse on white supremacist violence paints it as an aberration, despite the fact that it serves to reify the norm of white hegemony in German life. Public pressure to crack down on white supremacist violence as a movement, rather than a series of aberrations, would require the public to grapple with the role of white supremacy in German life — a painful conversation. To people who are not directly impacted by white supremacist violence, confronting its origins in society may be more difficult than simply choosing to be shocked anew each time it happens.

Critical State is your weekly fix of foreign policy without all the stuff you don’t need. It’s top news and accessible analysis for those who want an inside take without all the insider bs. Subscribe here.