Young migrants and refugees in Greece wanted to be heard. So they started their own newspaper.

Mahdia Hosseini, 28, and Fatima Sedaghat, 16, sit elbow-to-elbow at the corner of a long, wooden table, their heads nearly touching. They’re editing an article about the importance of setting goals for oneself, which Sedaghat penned for the next issue of Migratory Birds, a refugee-run newspaper in Athens, Greece.

The two young women are working at the Network for Children’s Rights youth center in downtown Athens, which serves young refugees, migrants and low-income Greeks. It’s open from morning until night, but is busiest just after school lets out around 3 p.m.

Migratory Birds, which boasts a bimonthly circulation of 13,000, is one of the only refugee-led initiatives in Greece left still standing. Like so many of the humanitarian aid programs across the country, however, recent funding cuts have meant an uncertain future for the newspaper that has given voice to dozens of aspiring journalists from the migrant and refugee communities in Greece since it began publishing in 2017.

Related: Mothers and babies lack basic needs in Greek refugee camps

Still, those behind it are optimistic that the newspaper, albeit with a smaller team, will continue to empower young people arriving in Athens.

“I’m thinking a lot about that [old] Mahdia and if she’ll ever return. But I think I don’t want that. I like the flavor of fighting and trying for my goals. I like this more, and I believe more in this Mahdia. This Mahdia is independent. I realize that the path that I have come on is the right one.”

For her part, Hosseini says, the newspaper experience has been transformative: “I’m thinking a lot about that [old] Mahdia and if she’ll ever return. But I think I don’t want that. I like the flavor of fighting and trying for my goals. I like this more, and I believe more in this Mahdia. This Mahdia is independent. I realize that the path that I have come on is the right one.”

Related: Olive oil company unites Cyprus with a ‘taste of peace’

On this afternoon, Sedaghat scrawls in Farsi in the margins of her notebook while Hosseini, editor-in-chief of Migratory Birds, offers suggestions. The next step will be to transcribe the rough draft onto an iPad where it will be translated into Greek and English.

Then, round two of editing. This is when one of the staff members of the Young Journalists program, funded by the UNHCR, Rosa Luxemburg Foundation and UNICEF, and offered through the Network for Children’s Rights, takes over. “Our goal is for the final article to be as good as possible,” explained Sotiris Sideris, a Greek journalist who is one of seven staff members for Network for Children’s Rights. Until last month, Sideris was the coordinator for the Young Journalists program and an editor for Migratory Birds.

“There are teenagers who write perfect articles with no help from us, but on the other hand, we have instances of people who need some help with the syntax, or some articles are missing conclusions or a strong introduction to keep the reader reading.”

Sideris added that they just polish the pieces — “the final outcome is all theirs.” He said, “We are not going to write their articles [for them]; we are just here to help them.”

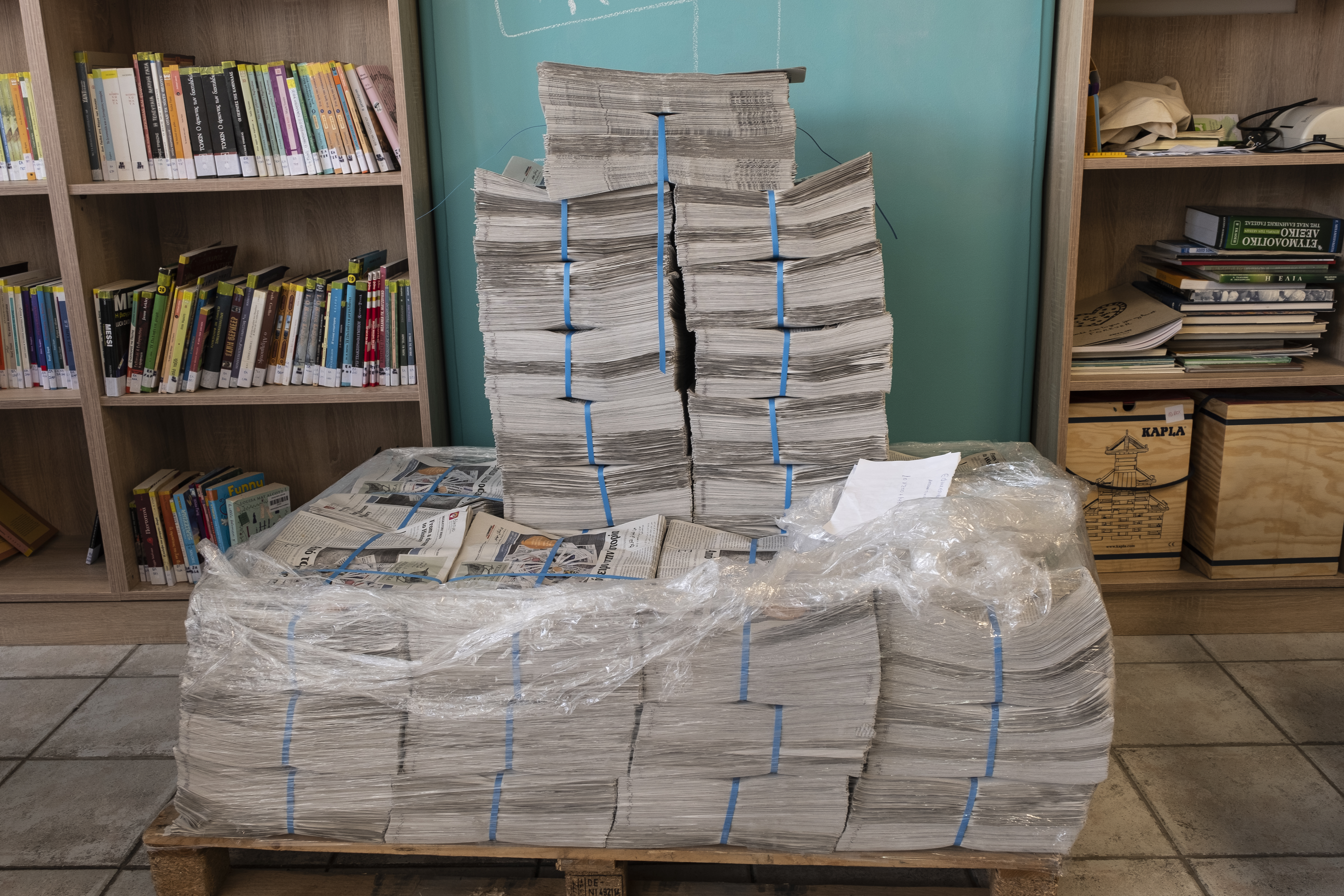

Later, the articles are sent to Efimerida ton Sintakton, a large Greek newspaper, for a final look. Then, a separate eight-page section for Migratory Birds is printed and slipped inside the daily newspaper.

Each issue of Migratory Birds contains reported articles, personal essays about life as a refugee, poems about love during the refugee crisis, recipes for traditional Afghan or Syrian food, and advice about where to find Athens’ best falafel. The newspaper is published in five languages that represent the tongues of its contributors: Greek, English, Arabic, Farsi and Urdu.

Related: These asylum-seekers won their refugee cases in Greece. Some wish they hadn’t.

Between its local distribution route, refugee camps and humanitarian organizations across Greece, 13,000 copies are distributed every two months. Not a small feat for a newspaper that was started by 15 Afghan girls in a refugee camp.

A rough beginning

Hosseini and Sedaghat, both from Afghanistan, met in the Schisto camp. In 2016, tired of the way refugees and migrants were represented in mainstream media, they and 13 other Afghan girls founded Migratory Birds, so named “because we thought we could fly through this newspaper,” Hosseini commented.

Their mission: to tell the realities of life for refugees in Schisto — their fears and frustrations and hopes and dreams. They were also desperate for an expressive outlet. According to the Albanian Greek journalist and supervisor to the magazine, Denisa Bajraktari, it sprang from a need “that these Afghan girls had, a need to be heard.”

“My father was always telling me, ‘If you want to improve, if you want to rise up and grow up, you have to start from the ground like a seed that you plant in the ground and starts growing.’”

“When we started to write our newspaper, we were sitting on the ground on just a piece of plastic,” Hosseini said. “My father was always telling me, ‘If you want to improve, if you want to rise up and grow up, you have to start from the ground like a seed that you plant in the ground and starts growing.’”

The girls worked tirelessly, confronting not only technical obstacles but also cultural barriers. “Many men in the camp didn’t agree — they thought they were still living in Afghanistan where women do nothing,” Hosseini said. “They said that women could not do this [newspaper], but what they didn’t know was that each comment made us better.”

Some of the camp’s residents mocked the young women. Worst of all, some of the families stopped their girls from joining the newspaper.

After eight months of hard work and perseverance, Migratory Birds published its first issue in April 2017. “We had a celebration in the camp, and the men of the camp came to our container and said, ‘We don’t have words to say to you,’ and they just clapped loudly,” Hosseini said, smiling and with tears in her eyes.

“After the men in our camp came to our container, our determination was so strong because we [saw] we were able to change the mind of Afghan men towards Afghan women. This was the biggest achievement,” Hosseini added.

An outlet for the voiceless

Migratory Birds is run from a cozy, three-floor youth center in the Kolonos neighborhood of Athens. The kitchen is well-stocked with fresh fruit, juices, hot drinks and Greek pastries. Shelves with books in five languages line the walls, and there’s plenty of seating as well as laptops and tablets and speedy Wi-Fi. The center is also used for language classes and journalism workshops.

For many of the young journalists who still live in camps on the outskirts of Athens, in containers, tents and other makeshift shelters during all weather conditions, the youth center brings a semblance of a normal life.

Hosseini was not the only one to brave the dangerous sea journey from Turkey to Greece, and many of the stories in the newspaper were about the danger of life back home and the trials of the journey to safety.

At the same time, many articles were about what it means to be a refugee or migrant in Europe. “I think we needed to be heard and for people to understand us, I mean refugees and migrants,” Hosseini said. “I want to show the real face of refugees and show them exactly who [we] are, because most people have a misunderstanding about refugees.”

It wasn’t long before boys joined the newspaper, too.

Like Mohammed al-Rifai, 18, from Damascus, Syria, who left Syria two years ago on foot with his mother. Rifai’s mother realized that he would soon run the risk of being conscripted into the army. That was the final straw.

Rifai did not want to become a soldier, either. “It’s not about whether you will stay alive, but how long you will stay alive,” he said. “In the end, there’s a line [death] and you can see the line. But you don’t know how long it will take to reach it.”

One night, he and his mother decided to leave, walking for days to reach Turkey. From Turkey, they boarded a rickety boat for Greece that arrived on Sept. 12, 2017. Like thousands of others before them, they spent several months in Moria camp before making their way to a squatlike living situation in Athens where he came across the youth center and Migratory Birds.

“It [the media] is not misrepresenting us. It is not representing us at all,” he said. “A lot of people in many places still hear about the war for the first time, so it’s not that they get it wrong so much as we are not heard. Nobody cares.”

“It [the media] is not misrepresenting us. It is not representing us at all,” he said. “A lot of people in many places still hear about the war for the first time, so it’s not that they get it wrong so much as we are not heard. Nobody cares.”

Migratory Birds also offers an opportunity for these youth to exercise their freedom of speech, something many of them never experienced in their own countries. “I’m enjoying that we all refugees are coming together in one place, meeting each other and asking each other things,” said Abdul Rashid, 16, from Afghanistan. “Also, I’m happy that refugees can write about what they passed through, and [that] they can do it without fear.”

Living without fear of persecution for expressing themselves, youth center staff say, is an important right for the young journalists. “Our aim is to work towards those rights and to let people who are participating in our program know their rights,” said Sideris. “Because we are talking about a journalism project here, it has to do with the right of expression — of writing and of expressing their ideas.”

Some of the girls who participate in the newspaper never went to school back in Afghanistan. Yet, not only are they now writing for the newspaper, they attend local public Greek schools, Sideris says.

An unstable future

Migratory Birds recently ran into another obstacle: funding. At the end of June, due to budget cuts and loss of funding, only three of the original seven full-time staff members, and one part-time cultural mediator remain. Production will continue as usual, but there will be far fewer people lending a hand.

“Funding is, of course, a big challenge — projects like the Migratory Birds are depending on funds,” said Maria Oshana, director of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation office in Greece. During 2015, she explains, there was an abundance of international organizations spearheading programs in Greece that supported various civil society initiatives and nongovernmental organizations in their work with asylum-seekers and migrants.

Today, however, a number of these organizations or their funders have withdrawn, which leaves many programs without the financial backing that makes their work possible. “At the same time, state institutions are far away from being able to step in, partly due to the ongoing economic [crisis], partly because of a lack of structures,” she said.

“The biggest obstacle is that [the participants] are leaving and moving [on]. They are people in transit. … People travel a lot within Europe, with official documents or not.”

Still, this isn’t the biggest challenge facing the newspaper. “The biggest obstacle is that [the participants] are leaving and moving [on],” Sideris said of the movement of refugees and migrants from Greece to other parts of Europe. “They are people in transit. … People travel a lot within Europe, with official documents or not.”

This is particularly destabilizing, he says, because they are working with teenagers who are usually in Greece with their families, and the decision to leave is not always their own. “Teenagers come here and find a new reality and a new norm that they can adapt to very easily compared to their parents because teenagers go to school, teenagers go to other activities like the newspaper, like music classes, English classes, theater, etc., but their parents come here with the will to move on as fast as they can.”

But it’s not only that so much time and effort are sunk into cultivating these young people who may end up not staying for more than a year or two. “It has to do with personal relationships, as well,” Sideris said. “Even if this is our job, and we should look at it as a job and not something else, you’re working with people every day so you are getting to know them well and you are creating a special relationship. We become friends after a while, it’s inevitable, and when they leave, sometimes it hurts.”

Still, the newspaper has achieved a lot in a short period of time. “The fact that all these children from such different cultures can work together in a room as equals, and can see each other as equals and never pay attention to where they are from, I think it shows that if there is will and power from within, [anything] can be done,” Bajraktari said.

Of the many obstacles the newspaper has faced, Hosseini said, “I think the ability and patience to face our problems, standing up after falling, the hope of better days, the presence of lightness after darkness, all of those beliefs give us the power to continue.”

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?