Audiences love the anger: Alex Jones, or someone like him, will be back

Alex Jones speaks during a rally for candidate Donald Trump near the Republican National Convention in July 2016.

Confrontational characters spouting conspiracy theories and promoting fringe ideas have been with us since the invention of American broadcasting. First on radio, then on television, the American audience has consistently proven eager to consume the rants of angry and bitter men.

Before Alex Jones and InfoWars, there was Glenn Beck.

A decade ago, Beck was hawking his conspiracy theories on HLN and Fox News. Beck eventually left HLN and lost the Fox News job, just as the inflammatory Morton Downey Jr. lost his lucrative syndicated broadcast decades earlier.

And before Morton Downey Jr., there was Joe Pyne, the war hero who eventually ended up railing against “hippies, homosexuals and feminists” on the airwaves in the 1960s.

Before Pyne, there was Father Coughlin, “the radio priest.” Coughlin was eased off CBS in the 1930s when he refused to allow the network to vet his inflammatory commentary.

You get the idea. Alex Jones is not unique. Nor do I believe, as a historian of American media, that he will be the last of his kind.

Public airwaves in private hands

Earlier this week, Jones’ InfoWars content was banned by Apple, Facebook, YouTube, Spotify and other web content distributors. It apparently violated policies against hate speech and inciting violence.

Whether you agree or disagree with the decision to constrict the reach of Jones’ toxic InfoWars videos, the upholding of these speech policies by commercial corporations represents a thorny historical issue in existence since the inception of broadcasting in the US.

Traditionally, it’s not been state censorship that’s cleansed American public debate. Rather, since the advent of electronic communication, commercial corporations have often acted out of fear of reprisal — from both the government and the public.

The US regulatory system for broadcasting began in 1912 when the Commerce Department assumed an administrative role that up until then had been haphazardly applied by different governmental agencies.

That system lasted until it was struck down by a US federal court ruling in 1926, which resulted in Congress establishing the Federal Radio Commission the next year and its successor, the Federal Communications Commission in 1934. Each regulatory entity generally ceded supervision of broadcast content to independent, commercial entities acting as licensees of the airwaves.

This means the US government has entrusted, and continues to entrust, private corporations with structuring public debate and discussion. Regulators are empowered to act but rarely do because the expectation that independent outlets remain responsible and civic-minded is deeply ingrained in the American system.

The web is governed by different protocols than broadcast media. The web was invented to share information widely and open up new spaces for community interaction, exchange and engagement that the old mass media made difficult (if not impossible).

The web’s inventors saw their role in contrast to broadcast media: as facilitating rather than censoring. The regulatory system that specifically indemnifies and protects them from content posted under their banners is a recognition of this status.

So, despite this new, open, democratic and accessible ideal of the web — the opposite of corporate-owned traditional broadcast media — the fact that mass web access to the American public remains largely controlled by corporate gatekeepers such as Facebook and Google may seem surprising.

Yet history, in the guise of Alex Jones and InfoWars, seems to have cast these social media and search engine giants into a more traditional role.

Google and Facebook might not want to police the marketplace of ideas, but it appears that they have little choice at this point. The creation they spawned is now littered with crackpots and conspiracy theorists, and it’s been exploited by a foreign government to damage the American political system.

But strong believers in the unfettered exchange of ideas as embodied by the First Amendment can take comfort in knowing the moves to limit peddlers of hate and lies like InfoWars won’t actually change much. There will be another Alex Jones in existence eventually.

It’s the American way.

From self-invention to crazy

When Richard Hofstadter, the noted American historian, published “The Paranoid Style in American Politics,” he identified a timeless and universal problem inherent in American political discourse.

Freakish conspiracy beliefs have continually given rise to such movements as the Know Nothings in the 1850s and the John Birch Society in the 1950s. Long before Hofstadter, Alexis de Tocqueville noted that a particularly American insecurity sprung from the ideology of democratic equality.

In societies where everyone knows their place — say, in the caste system of India or the traditional aristocratic hierarchies of Europe — the lack of personal opportunity and social mobility often creates apathy and acquiescence.

But in the United States, where everyone is officially born equal, we are supposedly empowered to make of ourselves what we will.

Whether it’s unscientific anti-vaccination theories, anti-Semitic rantings, or baldfaced scientific racism, anybody can be an “expert” in America simply by proclaiming their expertise.

Though this expertise might be assisted by celebrity, it’s in no way beholden to education or class. That’s the American way.

Failure begets conspiracy thinking

The Alex Joneses, Glenn Becks and Father Coughlins in our media world represent fissures in our dominant ideology of success. When the American Dream isn’t working out well, scapegoats must be found.

And a large audience of disappointed people looking for excuses will always exist. Their civics textbooks and teachers taught them that hard work, diligence, obedience to authority and responsible living inevitably results in economic prosperity.

But it often doesn’t work out that way. They feel lied to, and InfoWars exists to confirm their suspicions.

Because there will always exist a rabble to be aroused, this is the space that rabble-rousers historically exploit.

They speak to — and claim to speak for — not simply the downtrodden and downwardly-mobile; they also speak to those feeling wronged and forgotten. They simultaneously soothe and stoke the anxieties and insecurities of Americans living in a world that’s increasingly complex and beyond comprehension. Author Julia Belluz interviewed Jones’ fans and wrote, “I learned that Jones’s listeners felt let down by government, medicine and the media.”

People turn to Alex Jones and Glenn Beck for the same reason they tuned in the earlier incarnations — to obtain answers that explain their experience.

That’s a rational choice that sadly often results in an irrational outcome. The conspiracy theorists are always very good at giving details, but they tend to be far less effective at imparting information and knowledge.

Alex Jones promotes InfoWars as educational, but its pedagogical function resembles nothing so much as Trump University, which was sued by New York state for “… making false promises to convince people to spend tens of thousands of dollars … for lessons they never got.” Trump settled that suit.

Whether Jones believes his theories or not — and there exists some question about this — InfoWars looks like little more than a classic American con job. Even Alex Jones’ attorneys have argued that “no reasonable person” could believe what he says.

That’s ultimately why Jones is just a symptom.

Conspiracies are interwoven into the fabric of our national culture, and, as Jesse Walker pointed out in “United States of Paranoia,” they are so cyclical and persistent as to be thematically detectable across centuries. As long as insecurity and anxiety can be exploited, there will be new versions of InfoWars to pollute our nation.

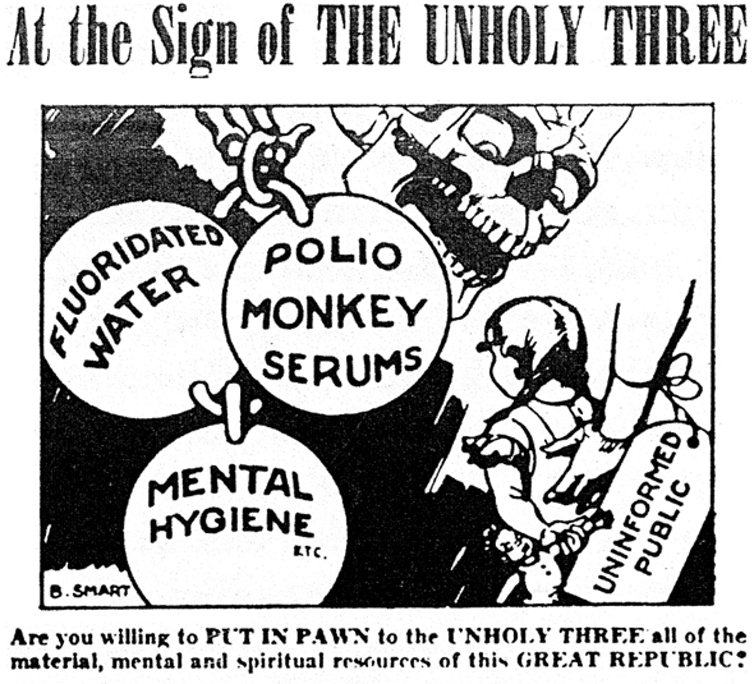

![]() How’s that for a conspiracy theory?

How’s that for a conspiracy theory?

Michael J. Socolow is anssociate professor of communication and journalism at the University of Maine.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

The article you just read is free because dedicated readers and listeners like you chose to support our nonprofit newsroom. Our team works tirelessly to ensure you hear the latest in international, human-centered reporting every weekday. But our work would not be possible without you. We need your help.

Make a gift today to help us reach our $25,000 goal and keep The World going strong. Every gift will get us one step closer.