As Israel turns 70, many young American Jews turn away

A protest by "If Not Now" outside the annual conference of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee in Washington, DC, March 2017.

Natalie Portman, the Oscar-winning actress, recently kicked off a massive storm of controversy when she pulled out of a prestigious award ceremony in Israel because, she said, she “did not want to appear as endorsing Benjamin Netanyahu.”

The response to Portman’s refusal to appear alongside Israel’s prime minister was intense. She was denounced by right-wing Israeli politicians. One labeled Portman’s decision as borderline anti-Semitic. Another suggested that her Israeli citizenship should be stripped. Born in Israel, Portman is a dual American-Israeli citizen.

The reaction within the American Jewish community was more divided. Some assailed her for being disloyal, deluded, or, at best, misguided. Others hailed her as a hero for publicly voicing her opposition to Netanyahu and his government’s hard-line policies.

Portman’s protest touched a raw nerve not just because of who she is — a world-famous Jewish celebrity and a well-known supporter of Israel — but also because of whom she is seen to represent. Her outspoken opposition to Netanyahu has been portrayed as typical of her generation of young American Jews whose attitudes toward Israel tend to be more critical than that of their parents and grandparents.

The end of ‘Israel, right or wrong’

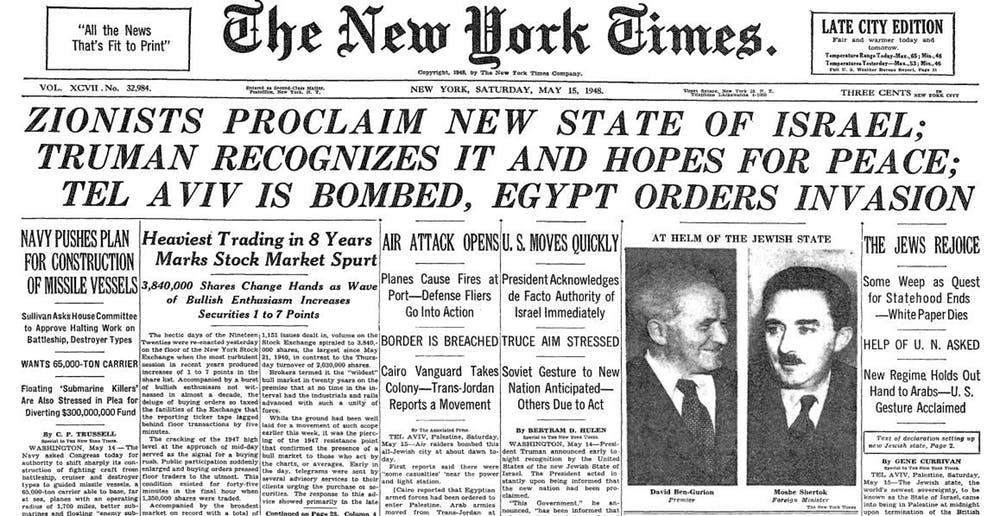

American Jews were initially indifferent or even hostile to Zionism when it first appeared. It took decades, and the mass murder of European Jewry in the Holocaust, to change their attitude. But after playing an important role in Israel’s establishment in 1948, most American Jews returned their attention to their own economic needs and social mobility, paying scant attention to the faraway, fledgling Jewish state.

It was only after Israel’s stunning victory in the 1967 Six-Day War that American Jews fell in love with Israel, which was then widely seen as the underdog in the Arab-Israeli conflict and an exemplar of a socially progressive, egalitarian society.

Supporting Israel came to dominate American Jewish public life and politics and became the one thing that almost all American Jews had in common. Their support tended to be unconditional and uncritical, especially during the two decades following the 1967 War when “pro-Israelism” became central to the American Jewish “civil religion.”

Even if they disagreed with what the Israeli government did, American Jews generally toed the line in public, as vocal criticism of Israel was taboo within the American Jewish community. Even in private, criticism was frowned upon. The prevailing belief was that only Israelis had the right to criticize their government since it was their lives at risk.

There has been a profound shift happening in American Jewry’s attitude toward Israel for some time (as I show in my book “Trouble in the Tribe: The American Jewish Conflict Over Israel”). Public criticism of Israel and acts of protest by American Jews have gradually become much more common, though they remain highly contentious — as is evident from the vitriolic reactions to Portman’s protest.

Portman, then, is hardly a trailblazer. She is simply continuing what has by now become something of a tradition of American Jewish protest against Israeli government policies. These protests have become much more frequent in recent years during Netanyahu’s second term in office.

Nor is Portman as typical of her generation of young American Jews as her many detractors and defenders seem to believe.

Discomfort with idea of Jewish state

Younger American Jews are overwhelmingly liberal in their politics — even more so than other young Americans. They are also “dovish” in their attitudes toward the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

In a major survey of American Jews by the Pew Research Center in 2013, for instance, only a quarter of Jews aged 18 to 29 believed that Netanyahu’s government was “making a sincere effort to bring about a peace settlement with the Palestinians.”

But the brand of liberal Zionism that Portman espouses — supportive of Israel, but often critical of its behavior, especially (but not only) toward Palestinians — is actually becoming unfashionable among her highly educated and politically engaged American Jewish peers.

For many, their problem with Israel is not just its current prime minister, its government’s policies and its nearly 51-year-long occupation of the West Bank. It is also Israel itself that they are uncomfortable with, specifically its identity as a Jewish state.

It is not only what Israel does that bothers them, but also what Israel is.

In a recent survey of Jews living in San Francisco’s Bay Area, just 40 percent of those between the ages of 18 to 34 said they were comfortable with the idea of a Jewish state. Just over a third thought that a Jewish state was very important. Most older Jews, by contrast, said they were comfortable with the idea of a Jewish state and thought it was very important to have one.

Colliding beliefs

Most young American Jews have been raised with two complementary belief systems: a political liberalism that emphasizes equality and opposes all forms of discrimination, and a non-Orthodox Americanized Judaism that emphasizes universalism and a commitment to social justice.

Many find it hard to reconcile the values they have internalized from these belief systems with the idea of a state that gives preferential treatment to Jews at the expense of its non-Jewish citizens, most notably its Arab minority — as Israel does.

Not only do many young American Jews take issue with what they regard, correctly or not, as the inherently discriminatory nature of a Jewish state, they also see less of a need for such a state.

Their chronological and emotional distance from the Holocaust – which more than anything else convinced earlier generations of American Jews of the need for Jewish statehood – is no doubt a large part of the reason why younger American Jews are less likely to believe that Jews need a state of their own to shelter and protect them. Indeed, a 2012 survey showed that the Holocaust had a much greater influence on the political beliefs of older American Jews than younger ones.

Younger American Jews are also far more accustomed to feeling secure in the United States. This sense, though, has been challenged over the past couple of years as the American far right has become emboldened and anti-Semitic incidents have sharply increased.

Nevertheless, they have grown up during an era in which American Jews are more assimilated, more affluent and more influential, culturally and politically, than ever before. These younger Jews are less inclined to believe that gentiles are hostile to Jews and that Jews are always at risk, as older generations of Jews have generally done.

Indeed, many younger American Jews, such as the writer Emma Goldberg, are more likely to identify with the notion of “white privilege” than with the notion of Jewish victimhood.

If, in their eyes, a Jewish state is discriminatory and no longer really necessary, then many younger American Jews struggle with supporting it. They feel ambivalent about Israel, if not altogether alienated from it. This is particularly true for the children of interfaith marriages — now almost half the population of young American Jews — whose Jewish identities tend to be less ethnic and more cultural.

![]() As Israel approaches the 70th anniversary of its establishment on May 14, many older American Jews will be happily celebrating the achievement of Jewish sovereignty after two millennia of statelessness. Many younger ones will be wondering whether the Jewish state is really something to celebrate at all.

As Israel approaches the 70th anniversary of its establishment on May 14, many older American Jews will be happily celebrating the achievement of Jewish sovereignty after two millennia of statelessness. Many younger ones will be wondering whether the Jewish state is really something to celebrate at all.

Dov Waxman is a rofessor of political science, international affairs and Israel studies at Northeastern University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.