Women are shown marching around the Eddie Warrior Correctional Center in Taft, Oklahoma, as part of their Regimented Treatment Program.

Editor’s note: On Wednesday, the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board heard Robyn Allen’s case. She’s the inmate we profiled in this story. Allen’s crime, trafficking in illegal drugs, carried a 20 year-sentence. Before being eligible for parole, she had to complete 85 percent of her sentence. She wasn’t even close to that. However, the board granted her commutation with time served. Now, it awaits Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt’s signature. During the proceedings, one board member, Honorable C. Allen McCall (a former judge), called out her excessive sentence, saying, “This sure seems like a true commutation to me.” Allen’s daughter, Cherise Greer, her granddaughter, Angelique, and her mother, Marianne, were all there and testified on her behalf. Allen will now go to a transitional home before joining the rest of her family in Duncan, Oklahoma.

Robyn Allen remembers the last time she saw her daughter. It was in an Oklahoma prison yard.

Allen, 52, hadn’t seen her daughter, Cherise Greer, for two years when their paths crossed last summer at Mabel Bassett prison, the state’s largest. Both were serving time for a 2013 methamphetamine conviction.

Greer was dressed in an orange jumpsuit and was being loaded into a van, headed to a minimum security prison in Oklahoma City. Greer and her mom weren’t allowed to speak because their conviction stemmed from the same crime.

As the guard turned away, Allen called out, “I love you,” to her daughter.

“She told me, ‘I love you mom, please don’t cry,'” Allen recalled as she wiped away tears.

At the time, Allen and her daughter were among more than 3,000 women serving time in the state. For over 25 years, Oklahoma has led the nation in the rate at which it sends women to prison. Roughly 151 of every 100,000 Oklahoma women are behind bars — twice the national average.

At a recent national event, Oklahoma Gov. Mary Fallin said her’s state’s number one ranking was a “dubious honor” and not something she’s proud of.

“I’ve jokingly told crowds we don’t have meaner women in Oklahoma. We just have some that have some issues,” she said.

Drugs and drug-related crimes, even simple possession, are some of the top reasons women enter the state’s criminal justice system. And, they’re staying longer. Stephens County, a mostly rural area where Allen is from, had the third-highest rate of women in prison. Allen is serving 20 years for possession of methamphetamines — two times longer than the state average.

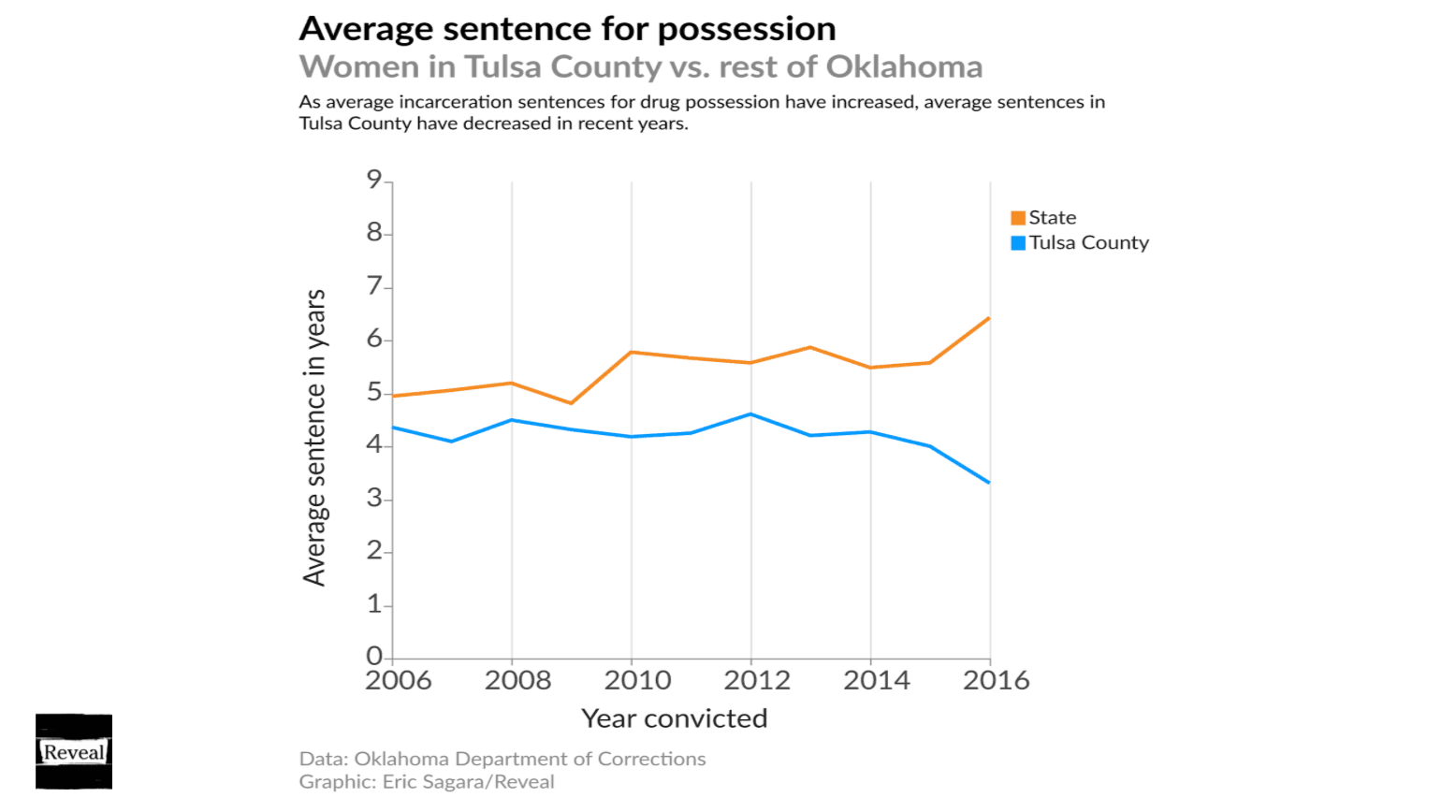

While other conservative states have reduced sentences for drug crimes, Oklahoma has headed in the opposite direction. Judges and prosecutors haven’t reformed the number of sentences for women. Some have increased women’s sentences for drug crimes over the last decade. Voters, tired of waiting for legislative change, used a referendum last fall to make drug possession a misdemeanor. Those changes took effect in July.

In Tulsa County, the rate for sending women to prison has decreased over the last seven years. That’s due, in part, to a program funded by oil billionaire George Kaiser that aims to send women to treatment instead.

Susan Sharp, a national expert on female incarceration and a professor emeritus at the University of Oklahoma, says women are collateral damage in the war on drugs. She wrote a book called, “Mean Lives, Mean Laws: Oklahoma’s Women Prisoners.” She took the name after having a conversation with a former colleague at the University of Oklahoma about the state’s prison system.

“He very proudly showed me the women’s prison and then even more proudly told me that Oklahoma had the highest female incarceration rate,” Sharp said.

“I asked him why he thought that was. He looked at me and he said, ‘Oklahoma has mean women.’ And after I picked my jaw off the floorboard of his car, I thought about not coming here. … Then I decided that maybe they needed me here.”

Her research shows that poor women in rural areas receive longer sentences, while those who can afford private attorneys get less time for the same crimes.

“There are some counties that are extremely harsh, that almost anyone convicted will go to prison,” Sharp said. “The district attorney is the most powerful player in the courtroom. … And if they are trying to build a reputation of being tough on crime, they’re basically going for the low-hanging fruit.”

Don’t shoot her!

Allen and her 32-year-old daughter were low-hanging fruit.

Duncan, where Allen lived, is in the southwest part of the state. A sign on the way into town reads, “Outlaw Country.” It’s known for its rich farmland and blooming crepe myrtle bushes. Wind farms dot the fields leading into the town. A statue celebrates Erle P. Halliburton, who founded what is now known as Halliburton in 1919.

On a February afternoon, the Stephens County sheriff kicked in Allen’s door. She had been expecting them.

Allen was sitting on her bed, smoking a cigarette when 28-year-old Greer, who was living at home, dropped to the floor. Allen saw a rifle aimed at her daughter’s forehead and was afraid she was going to get shot.

“Don’t shoot her; it’s me,” said Allen. “I’m the bad one.”

Officers found methamphetamine stashed in Allen’s bedroom along with other drug paraphernalia. At the time, she was one of five adults living in the house along with her 4-year-old granddaughter. No one was working and Allen was selling drugs to support them all. She’d hurt her back while working at a local hotel and was waiting for disability benefits that never came. Allen said she’d been trading the Lortab and Xanax medication she got from the doctor for meth. She admitted to using and selling it.

This was her first felony offense. She had two misdemeanor convictions more than 20 years ago. One for writing a bad check and another for failing to return a video game system to a local movie rental store.

The prosecutor in Allen’s case asked for a sentence of 30 years, while her lawyer asked for leniency and entry into a drug treatment program.

Allen told Judge Joe Enos she’d been addicted to drugs half her life and that she had sought treatment, but no beds were available. Enos has a reputation for being stern.

“You are a specific provider and supplier of these drugs to many of the individuals who have succumbed to the terrible effects of methamphetamine,” Enos said.

The drug was linked to the deaths of 167 people that year in Oklahoma.

In the end, Allen took what’s known as a blind plea, leaving her sentence up to the judge, who gave her 20 years for trafficking in illegal drugs. That’s twice the amount recommended by a state task force for that crime. When Allen got to prison, she found out just how long her sentence was.

The officer in Assessing and Receiving, Allen recalled, said, “Robyn, who did you make mad?” referring to her long sentence. But two other women in her pod had received similar sentences for similar crimes in the same county.

Allen wrote Enos a letter asking him to reduce her sentence because she felt remorse and was trying to get herself straight. She didn’t hear back.

“I poured my heart into that letter,” Allen sobbed.

Neither the district attorney nor Enos responded to multiple requests for an interview.

Treatment, not prison

If the current trend continues, the state’s prison system is expected to grow by nearly 60 percent over the next 10 years. Prisons are already bursting at the seams. Mabel Bassett is over capacity. Bunk beds line the dayroom, where prisoners take classes, socialize and make phone calls.

Joe Albaugh, the director of the state’s prison system, wants reform. Albaugh directed FEMA under George W. Bush, so he’s used to handling a crisis. Oklahoma’s ballooning prison population, however, is something else.

From his office on the campus of a minimum security prison in Oklahoma City, Albaugh tried to answer the question of why some of Oklahoma’s prison sentences are so long.

“Judges say, ‘You know, you’ve been before me five times, Suzy Jones, and there won’t be a sixth time. I’m going to send you to prison so you can get some help.’ Practically, there is no help in prison. We are very limited in our programs, and there just is the belief that we ought to “lock them up, throw away the key.” And it doesn’t work.”

Albaugh says the state needs to spend less money sending women to prison and more money on treatment. The state spends $500 million a year on prison — about twice as much as it costs to provide treatment on the outside. This, in a state where school budgets have been slashed and some districts can only afford to send kids to school four days a week.

“Ninety-four percent of our population returns to society. And what do we want? We want better neighbors. And the way we’re doing things and approaching things in our criminal justice system when it comes to prisons, we’re just a warehouse organization; that’s all we are. If we don’t do something different, our population with women will increase 57 percent over the next 10 years.”

That growth is huge when compared to other red states like Utah, Mississippi, Georgia and Texas. They’ve chosen to reduce their prison population and reform their criminal justice system.

Tulsa DA Steve Kunzweiler has one theory why women like Allen in smaller towns get longer prison sentences. He’s been a DA in mostly rural counties and says, in small communities, everybody knows everybody’s business.

“Everybody knows who that lawbreaker is. And so there is an expectation to, at some point, ‘get this person off my street because I’m tired of them breaking into my barn or breaking into my outbuildings.’ It’s hard to convince the community that you need to wrap your arms around the very person that you’re cognizant that is probably going to be going out stealing stuff.”

Impact down generations

Incarceration doesn’t just affect one woman. When you send a woman to prison, it can affect generations of Oklahomans. Often, women are the sole breadwinners and caretakers of children. When they go to prison, kids may end up with their dad, who may be the reason mom is in prison in the first place. Some kids end up with other relatives who don’t want them or have a full house already. Some end up in foster care.

A recent study by the Oklahoma Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services shows that if mom goes to prison, there’s a good chance one of her kids will, as well. Susan Sharp knows about that domino effect.

“You can sometimes find … three generations of a family incarcerated at the same time. For example, a mother, a grandmother, the daughter,” she said.

The majority of women incarcerated in Oklahoma are doing time for nonviolent crimes and drug-related offenses. As Sharp explains, women, particularly mothers, are treated more harshly and sometimes receive longer sentences than men because their crimes are drug-related.

“I think the general population of the state feels that a woman — particularly a woman who has children — who uses drugs, violates all the norms in a way that they find unacceptable and they would rather see those children grow up in foster care than to be with a mother who had a drug problem.”

Sharp also explains that Oklahoma has outdated attitudes about what constitutes proper womanhood.

“This is an extremely conservative state and an extremely religious state and very evangelical and a lot of biblical literalism. So, the belief that women have a certain role in society — that role is to give up themselves and put themselves and their own wants, goals, desires secondary to taking care of their husband and children.”

Women in recovery

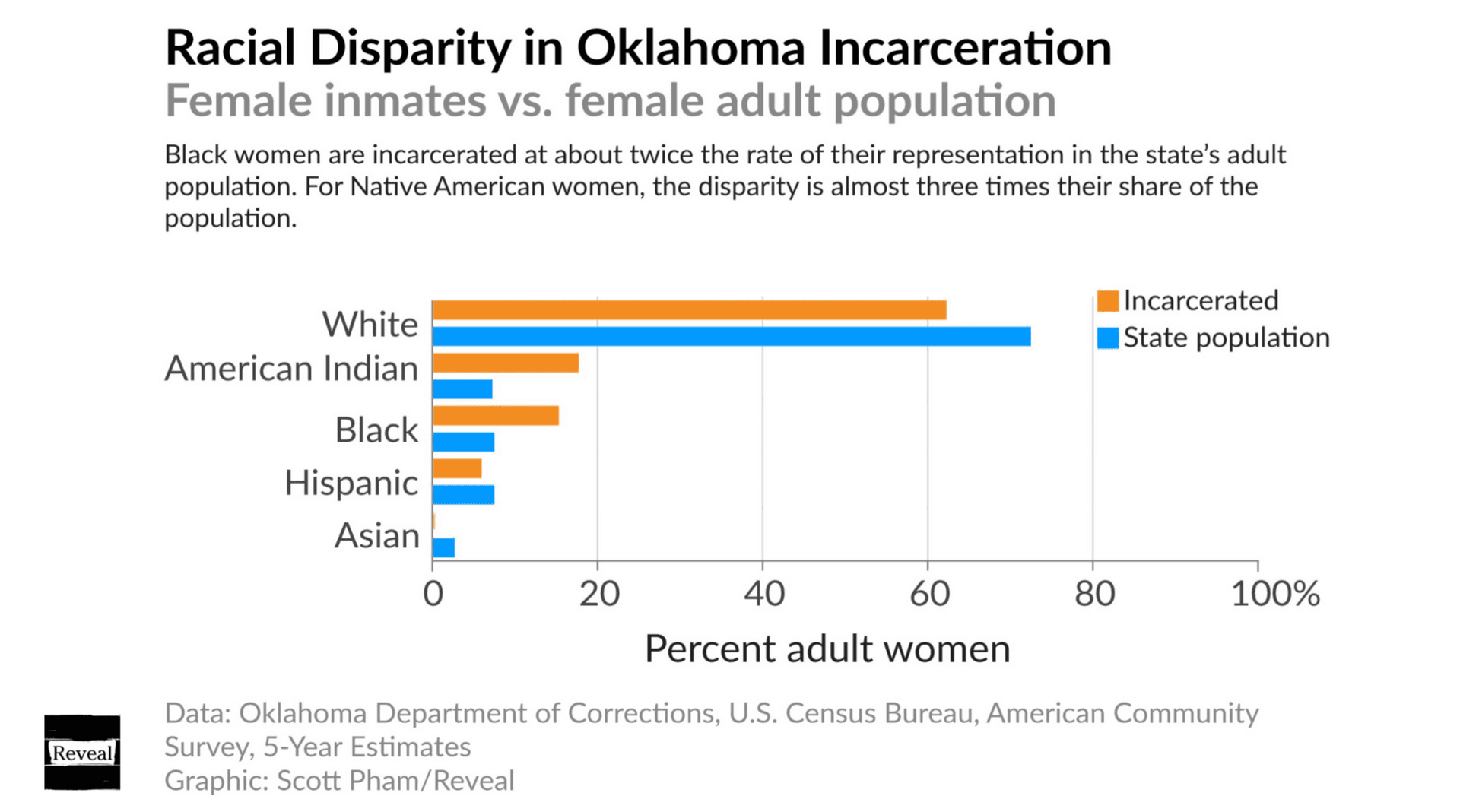

According to the data, Native American women comprise 12 percent of Oklahoma’s prison population, while representing only 9 percent of the state’s population. Muscogee Creek Nation’s Reintegration Program is one way to ease the transition from prison to home. It’s funded by the tribe and helps ex-offenders get jobs, housing and rebuild their lives while supporting Native American culture. Tony Fish, the program manager, laid out the key reasons he thinks the program works.

“I feel like, on our state side, we don’t hold the value in people like we do our tribal side, because that is part of our culture and who we are,” he said. “We hold value in people, and we look at things through different lenses.”

The program isn’t just for Native people. Fish explained they have resources for non-Indians, too. They visit prisons frequently, targeting inmates when they are about to go home.

So far, the program has helped hundreds of inmates transition from prison yard to a home since 2012. It’s funded by a mix of money from the tribe’s gaming efforts and other business ventures.

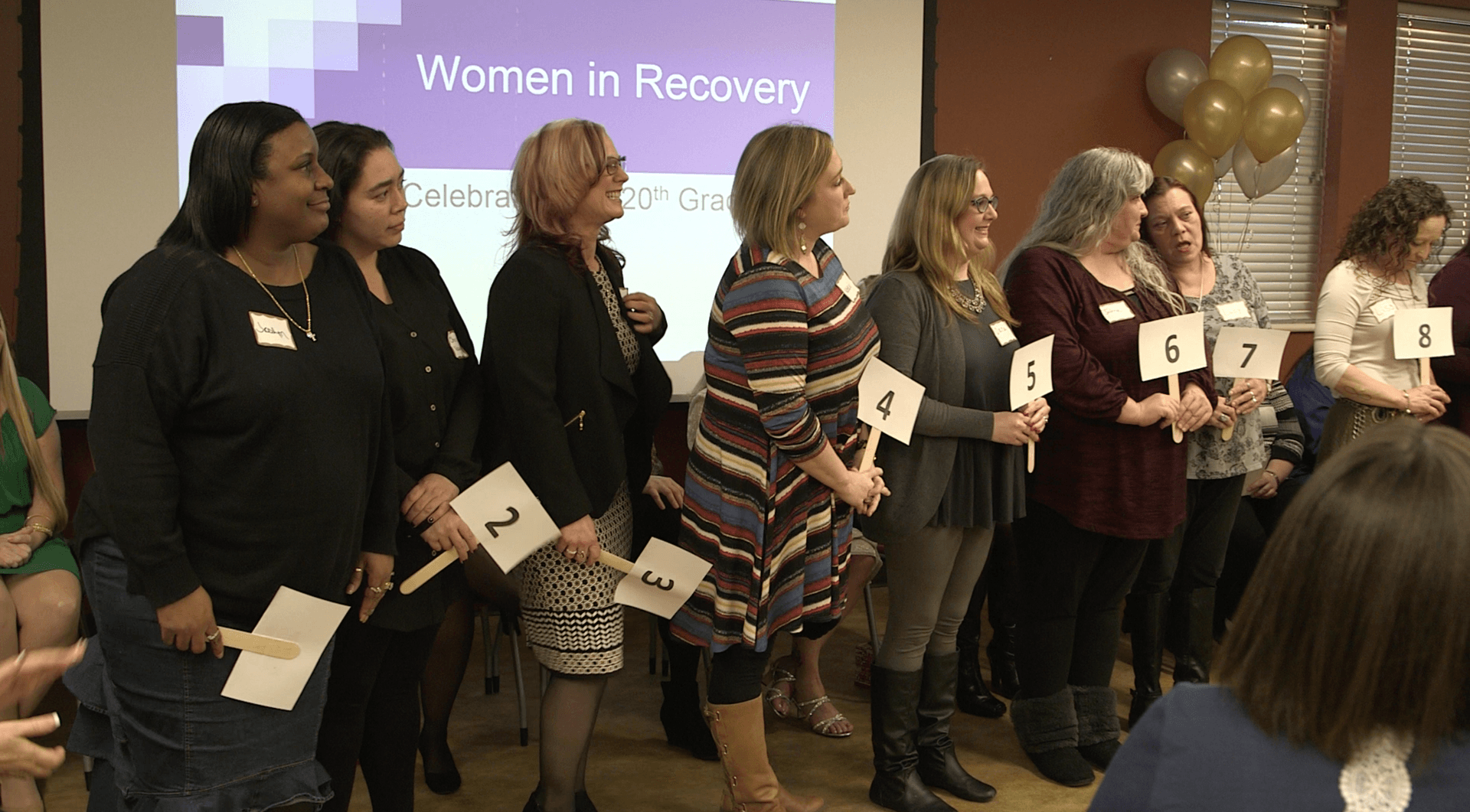

Another bright spot is a program in Tulsa called Women in Recovery. When a woman pleads guilty, a judge can sentence her to Women in Recovery. The program lasts 12 to 18 months and has helped hundreds of women with job training, finding a place to live, reconnecting with their children and dealing with the trauma that landed them in prison in the first place.

At a recent graduation, Rona Stone spoke to a crowd of supporters and families. She spent nearly her entire life suffering from addiction, selling drugs and losing her teenage son to gang violence before she came to Women in Recovery.

“I have been trying for 27 years to fight this disease on my own, but I realized I just couldn’t do it. Women in Recovery saved my life,” Stone said.

If programs like Women in Recovery work so well, then why aren’t there more programs like it in the state? One of the biggest reasons is lack of funding. The program in Tulsa is funded by oil billionaire George Kaiser. The other reason is pushback from powerful prosecutors who don’t favor reducing sentences.

Oklahoma will now allow inmates who are within 18 months of completion of their sentence and are serving time for nonviolent offenses to be released into a community supervision program. This change is meant to reduce crowding in prisons like Mabel Bassett, where Allen is serving time.

But Allen won’t benefit — at least, not for a long time. She’s only four years into her 20-year sentence and won’t be eligible for parole until 2019. Her daughter is likely to be released within the next year, though.

“Meth has destroyed my life,” said Allen. “I’m never doing that drug again.”

This story is based on a yearlong reporting project produced along with Reveal’s Ziva Branstetter, Harriet Rowan and Eric Sagara. To hear the radio version of this story, go to Reveal’s website: Does the time fit the crime.