Chinese Nobel Peace laureate Liu Xiaobo remembered

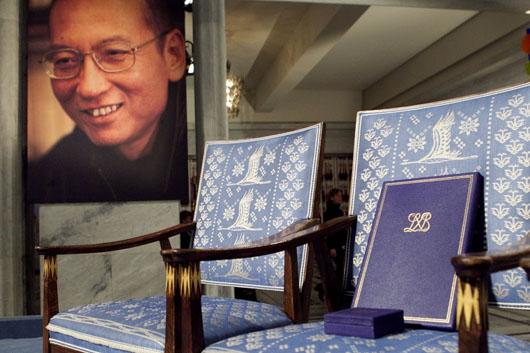

Liu Xiaobo's empty chair at 2010 Nobel Peace Prize Ceremony in Oslo, Norway; Liu was in a Chinese prison.

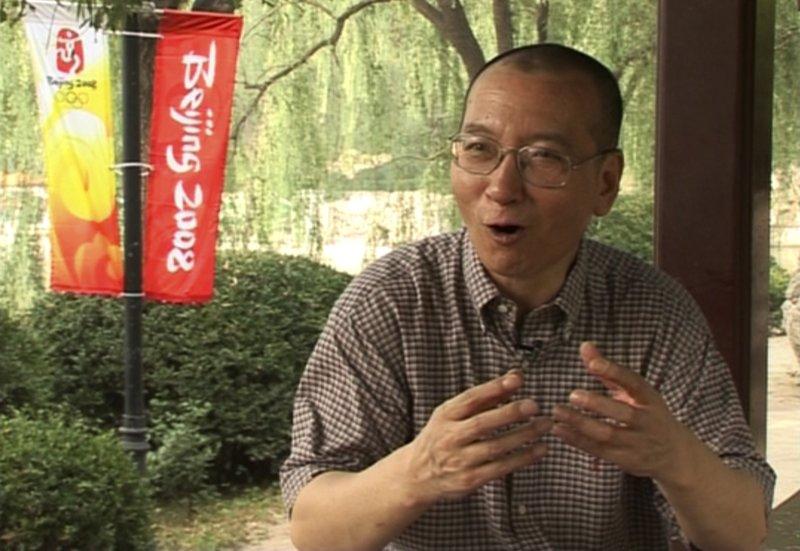

On a hot July 4 in Beijing, in 2005, I met a brave man in a near-empty restaurant.

He wore shorts and a T-shirt. He had a close-cut haircut, glasses, and a stammer. He was Liu Xiaobo, a former professor of literary criticism who had spent years in prison and in workcamps for challenging China’s leaders to do better, to allow more of the freedoms enshrined in China’s constitution, to allow an evolving Chinese society to evolve politically, too.

That included joining some of his own students in the Tiananmen pro-democracy protests in 1989 and, when troops were already firing on civilians elsewhere in Beijing, he helped negotiate with troops surrounding Tiananmen Square itself, so the students could leave peacefully.

When Liu and I met that hot July day, I asked him if he thought he’d see democracy in China in his lifetime.

It was time for China’s political system to change, too.

“But I don’t think the change will be the same as the overnight change in Eastern Europe (in 1989-90),” he said. “China is a big country and its demography is quite complex. China’s change will be a gradual process. I hope China will change in a gradual process.“

Liu Xiaobo did not see democracy in China in his lifetime. He died on July 13, 2017, of liver cancer, under guard at a hospital in the northeastern Chinese city of Shenyang, after serving seven years of an 11-year prison sentence for, the charge said, seeking to subvert state power.

The Chinese government has tried hard to erase Liu Xiaobo from the memories of Chinese citizens. Mentions of him have been forbidden in state-run media, and are wiped clean from social media. But when he died in his hospital bed, released from prison too late for any treatment that might have helped him, many Chinese evaded the Chinese censors and posted on social media, in code, since they couldn’t say his name.

Some posted an image of that empty chair. Some posted the dates of his birth and death, 1955 to 2017 — 61 years. And some posted a video of a Beijing thunderstorm that flashed lightning the night he died, saying these were the heavens, welcoming a hero.

So whose century is it, in the struggle between authoritarian power and individual rights? It's too early to say. But Liu Xiaobo will be remembered in the world, if not yet as widely in China due to aggressive government censorship and attempts to erase his name from public memory, as someone who recognized how important it was to try to move the needle in the right direction, and who spent his life trying.