World Cup demonstrates why international games leave millions behind economically

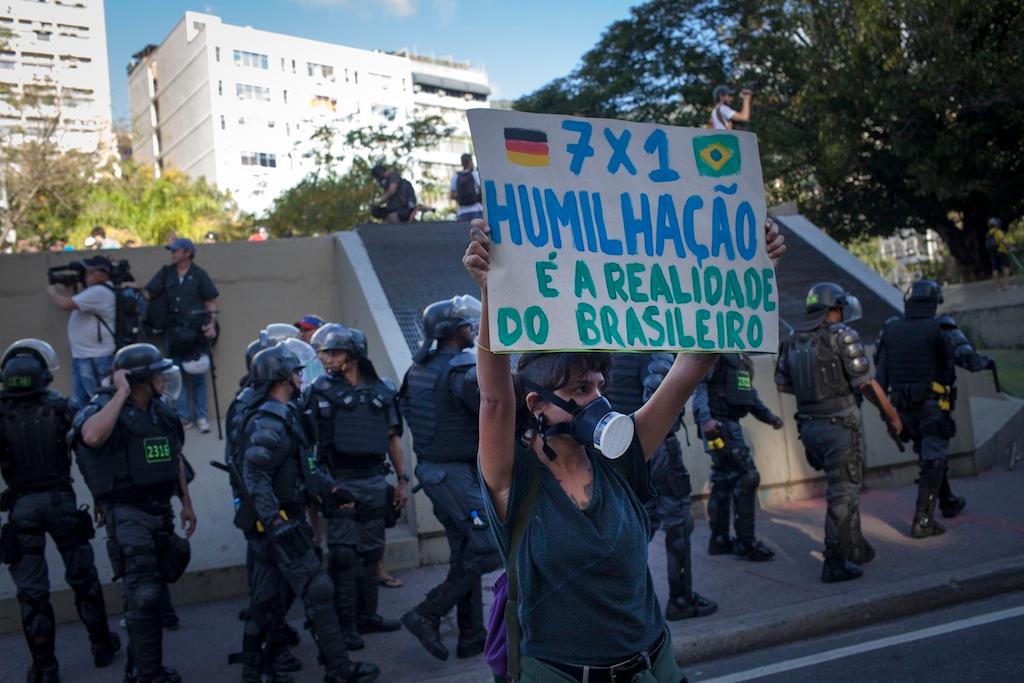

Police stand guard on the sidelines of an anti-World Cup protest near Maracana stadium on the last day of the World Cup soccer tournament, July 13, 2014 in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Anti-World Cup protesters criticize that the government should spend money on improvements for education, health and housing, instead of soccer.

NEW YORK — We often hear sport is a great equalizer that can level out distinctions like class and stomp out problems like racism. In fact, development agencies have long embraced sports as a means to transcend violent rivalries, especially in conflict-torn communities.

Kingsley Ighobor, information officer in the Africa Section for the United Nations, recalls the powerful ability of sports — soccer for men, kickball for women — to build trust between former combatants and civilians in post-civil war Liberia.

“People that had not had a reason to smile for many, many years, suddenly, they are all rallying around their team, they are happy,” he said. “Sports can enhance social cohesion within communities.”

Yet, against the fading backdrop of national colors and anti-racism banners in Brazil, the World Cup’s real price tag will soon emerge. For now, we are left wondering— what will be the tournament’s legacy for Brazilians?

Even with sports’ potential for social inclusion, the vast sports industry may simply be structured to exclude entire populations economically. The World Cup that just wrapped up in Brazil — the most expensive ever — clearly illustrates this point.

This was a World Cup for the affluent. If CNN Money’s estimate that a minimum of $3000 is needed to cover costs to fly to Brazil to watch a few games over several days, then the citizens of only 29 out of 189 countries have sufficiently high monthly incomes to afford the trip. People from Italy, Russia and Spain would not make the cut.

To no one’s surprise, FIFA, soccer’s governing body, stands to gain the most. In 2010, FIFA made $2.4 billion in revenues from the World Cup in South Africa, mostly from ad and TV deals. In Brazil, that figure will rise to $4 billion, a number greater than the national budgets of 108 countries.

It raises the question of why people play and watch the game. What is the incentive structure that underpins this multi-billion dollar industry?

For Brazil, it was a costly privilege to host the World Cup. The government spent an estimated $11 billion to prepare for the tournament and will spend many more millions maintaining the arenas.

Visitors and consumption by those attending the games did inject money into the economy. Looking at South Africa’s experience documents the imbalance between costs and benefits. South Africa spent $4.5 billion to prepare for the World Cup in 2010. The returns were nowhere near the break-even point: about $500 million, just over 10 percent of total costs.

It’s easy to see why Igbohor believes sport is most effective when based around more altruistic purposes.

“(Sports) can foster peace, reconciliation,” he said. “It can bring people together, as a unifying force. You can use sports to promote a lot of the issues that need to be promoted.” One of those issues has been racism in football, the target of a grand FIFA campaign.

But even in that regard, this World Cup hasn’t done very well. The Fare Network, which tracks cases of discrimination in football, found at least 14 clear instances of racial abuse from fans during the World Cup in Brazil.

In the end, money is the clear reason countries fight to host events like the World Cup and the Olympics. Athletes know that to successfully display their talents can lead to new contracts and sponsorship deals. Any issue that does not contribute to that singular focus, like racism and poverty, is viewed as an enemy. That is why athletes from humble backgrounds often talk about “escaping” poverty.

“As a vehicle out of poverty, sports are pretty limited,” said Benjamin Radley, a Welsh national who worked in Burundi in East Africa and played on Burundi’s national rugby team. “What we have now is a very exploitive elite structure and a very small number of footballers within that structure that are also making millions a year, but you have a mass of footballers who are struggling to make an existence,” he said.

Radley got a close up look at sports in a resource-poor context during several years in the region. Sometimes he saw team owners recruit players by offering them menial jobs. He recalls one football player who was paid $160 — less than half the average income — to play in neighboring Rwanda. That was a success story.

Ultimately, Radley believes sports may be reflective of our societal challenges. We use football as a proxy to talk about problems like wealth, inequality, and even anti-immigration sentiment — without addressing their real causes.

Yet, Ighobor sees a way the social and economic issues can find solutions together. Sports, he says, help lay a stable foundation, which can then encourage economic investment and development.

Brazilians will hope that was the thinking behind the decision to host the tournament. This World Cup has been about many expectations. A host nation that expected its team to win on home soil, a citizenry that expected joy and international prestige, and protesters who expected a better fate. We should expect now to hear from them again, as the true costs of this World Cup start to add up.

Jefferson Mok is a media development specialist. He lived in Burundi from 2008 to 2011.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!