Why the Islamic State is making Indonesia and its neighbors nervous

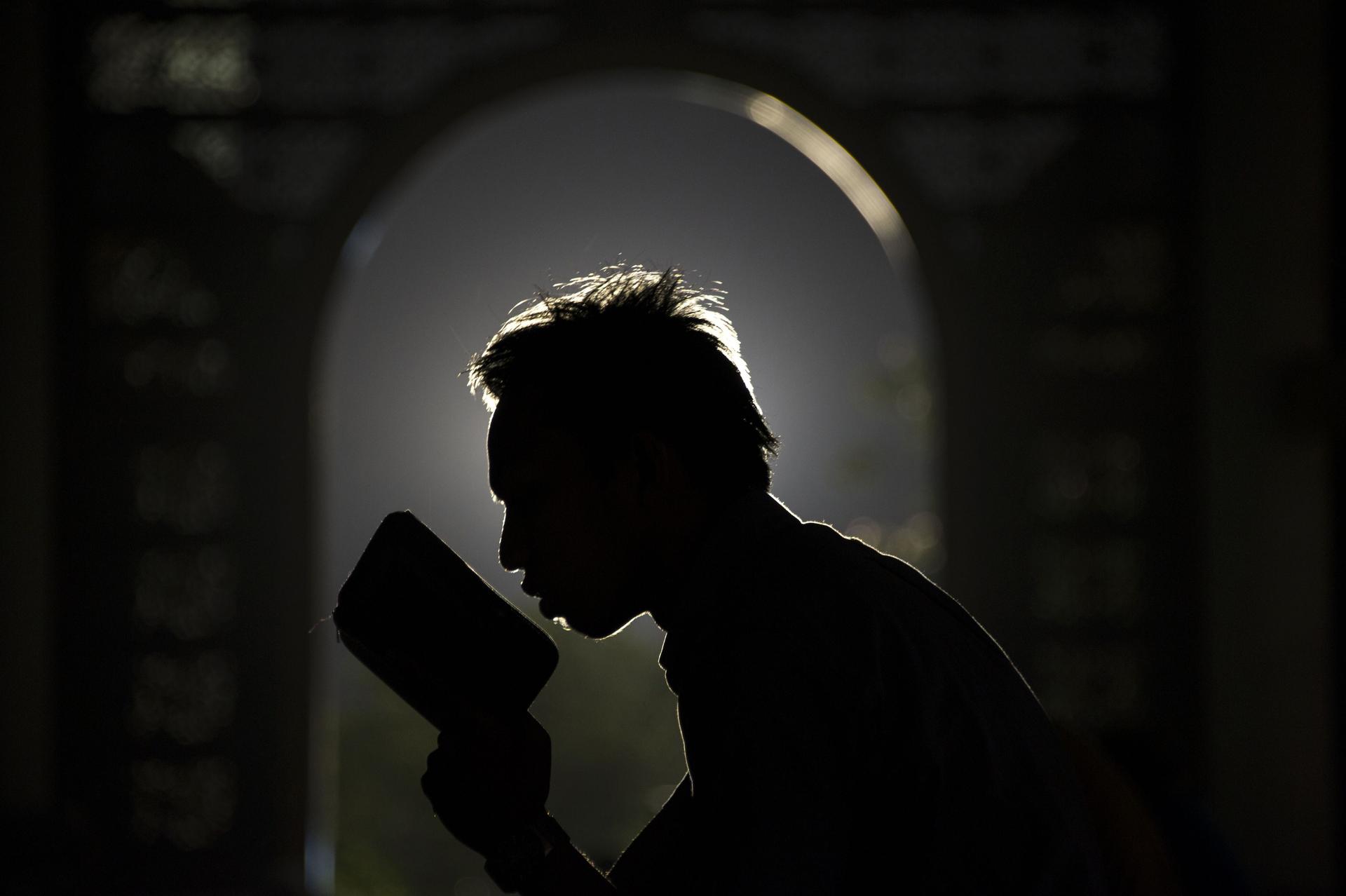

An Indonesian Muslim devotee prays over a Quran as the month of Ramadan continues at a mosque in Surabaya on the eastern Java island on July 8, 2015. Indonesia is the world's most populous Muslim-majority country.

MELBOURNE, Australia — When Tony Abbott was elected prime minister of Australia in September 2013, he promised a foreign policy approach that would be “more Jakarta, less Geneva.”

It was a pragmatic goal, given Australia and Indonesia's proximity and close economic ties. Since then, the partnership has been beset by diplomatic crises, such as the influx of refugees and migrants using Indonesia as a base to reach Australia and the execution of two Australians convicted of drug smuggling in Indonesia.

But increased urgency about the Islamic State (IS) has renewed a relationship of necessity. As the world’s most populous Muslim-majority country, Indonesia presents an attractive target for IS recruitment and radicalization efforts. The two countries recently laid out a plan for closer cooperation on regional counterterrorism solutions, targeting the online narratives and financial networks supporting IS.

“Cooperating on counterterrorism is in the interests of Australia just as much as it is in the interests of Indonesia,” Australia’s Justice Minister Michael Keenan told the Sydney Morning Herald after meeting with Indonesian terrorism experts last month.

The agreement came just a few weeks after Indonesian President Joko Widodo called IS his country’s top international concern in an interview with The Wall Street Journal. Widodo, who was elected in October 2014 on an anti-corruption and domestic policy platform, has been criticized for being slow to act against terror threats.

Indonesia’s per capita contribution of fighters to IS is relatively low, but the uptake of ultraconservative Islam in recent years suggests that support for the establishment of an Islamic caliphate, a central part of the Islamic State’s ideology, may be broader than for the radical jihadist movement itself. The Herald, for example, documented last month that a mosque in suburban Jakarta less than a mile from the US Embassy is a recruiting center for IS.

“The moment Indonesia becomes a stronghold for extremist ideology we’ll be in a bad situation,” said Nico Prucha, research fellow at the International Center for the Study of Radicalization at King's College London.

Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), the largest independent Islamic organization in Indonesia, has been working to make sure that doesn’t happen.

“We are nurturing our communities to defend them from being attracted to these radical ideas. In the urban areas, we have people that really engage with the issue. They are delivering speeches, propagating our interpretation of Islam,” said Yahya Cholil Staquf, general secretary to the NU’s Supreme Council.

With a membership of around 50 million Muslims throughout the country and a large network of Islamic scholars, NU’s arguments carry weight in Indonesia. So do those of Muhammadiyah, Indonesia’s second-largest Islamic organization with 20 million members. At its annual congress this month, Muhammadiyah reasserted its longstanding support of Indonesia remaining a secular state.

Even so, Yahya Cholil Staquf sees limitations to what Islamic organizations can accomplish: “We are lacking in resources compared to what [the radicals] have,” he said. “We have the feeling in recent years of losing more battles on the ground.”

Indonesia has not banned travel to Syria, though it has increased monitoring of citizens traveling to Turkey. Critics of Indonesia’s approach say it is difficult to know who exactly is fighting with IS and, crucially, who is returning to Indonesia from the battlefield.

Contrast this with Australia’s recent Foreign Fighters Bill, which made it illegal to travel to countries declared “no-go” zones, such as Syria. While human rights activists and advocates in Australia’s Muslim community condemned the legislation as an erosion of citizens’ civil liberties, the bill received widespread support in parliament.

“I personally don’t think the Australian approach is the best one to take, but it certainly is the most popular,” said Gregory Fealy, associate professor of Indonesian politics at Australian National University.

Whether Indonesia will follow Australia’s example is not yet clear.

Sidney Jones, director of the Jakarta-based Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict (IPAC), told The Sydney Morning Herald that while new terrorism laws are being drafted, few members of Indonesia’s parliament see the threat posed by IS as a top priority.

On the other hand, as C. Holland Taylor, an expert on the process of Islamization in Southeast Asia and co-founder of the nonprofit LibForAll, pointed out, “The debate in the Indonesian government may not be playing itself out for the media the same way it is in the West.”

“In Indonesia, if they decide to do something, they will do it. I think they’re looking at all this and they’re deliberating,” said Holland, who lives in Central Java.

Even if that is the case, stricter legislation may not provide the whole solution: “It can help a bit, but it’s not touching the root of the problem, the radical ideas,” said NU’s Yahya Cholil Staquf. “We need to make the voice of moderate Islam louder. We need to strive for a societal consensus that marginalizes these radical ideas.”

Most terrorism experts agree that the greatest threat to Indonesia’s national security will occur when IS recruits return home. But in the meantime, foreign fighters are reaching out to sympathetic citizens through personal networks and online channels. And the Islamic State’s formation of a dedicated unit of Indonesian, Malaysian and Filipino fighters in the Middle East, called Katibah Nusantara, is helping to spread battlefield propaganda on Indonesian-language websites and social media platforms.

In an attempt to disrupt the narratives coming out of Syria and Iraq, Indonesia’s Ministry of Information and Communications Technology monitors websites and social media for and removes radical content. But a 2014 report by IPAC found that “[c]losing Internet sites is a largely futile exercise.”

“Challenging the content may be a better way to go but it has to be done in a far more sophisticated way than has been done by government agencies thus far,” the IPAC report continued.

Part of the problem in Indonesia stems from a 2009 decision by the National Anti-Terrorism Agency (BNPT) to divide counterterrorism duties between the police and military, assigning the task of prevention to the military, which had no prior experience in this area. The misstep was a failure that plagues Indonesia’s deradicalization efforts to this day.

Currently, BNPT officials in charge of prevention believe that a lack of nationalist pride causes Indonesians to fall in with IS, said Fealy, who recently has been conducting fieldwork in Indonesia.

“This is a very rudimentary view,” he said. “The narratives being presented to Indonesians aren’t really going to the heart of the radical fringe.”

Rather, experts suggest that NGOs that are well-versed in jihadist ideology, Islamic scripture and social media will have the greatest success in countering IS narratives online.

So far, such attempts in Indonesia have been piecemeal. Australia’s Living Safe Together initiative, which doled out small grants to individuals and community groups, also was seen as largely ineffective and unsystematic in its approach. In one case, a car mechanic with no prior experience received funds to run an intervention program.

Recently, however, a more robust federal initiative was launched, called the Australian Intervention Support Hub. The Hub applies evidence-based research to improve online and offline intervention programs in Australia. It also aims to develop regional capability among civil society service providers in countries such as the Philippines and Indonesia.

“Our objective is to develop some elements of our programs in Indonesia, but we won’t just roll out a program across different countries. They need to be country-specific, if not even more locally specific,” said Clarke Jones, co-founder of the Hub.

With Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull now at the helm following a power shakeup that ousted Abbott, and a joint summit on extremist funding sources set to be held in Sydney in November, cooperation between Australia and Indonesia on counterterrorism will require a greater degree of trust than was typically present in the past.

In July, for example, The Intercept revealed the Australian Federal Police (AFP) spent several months tracking the apparent radicalization of two Indonesian pilots on social media.

The Guardian then reported that although Australia sent a report on the pilots to law enforcement partners in Turkey, Jordan, London, the US and to Europol, Indonesia only learned of the potential terrorists after the story was published online.

The Indonesian national police chief, General Badrodin Haiti, cautioned against assuming the pilots had actually joined the Islamic State.

“They have sympathy for the IS struggle, that’s what there is,” he said. “From there, the AFP considered them IS.”

This story was presented by The GroundTruth Project.