Syria’s refugee children need education, lest they become a lost generation

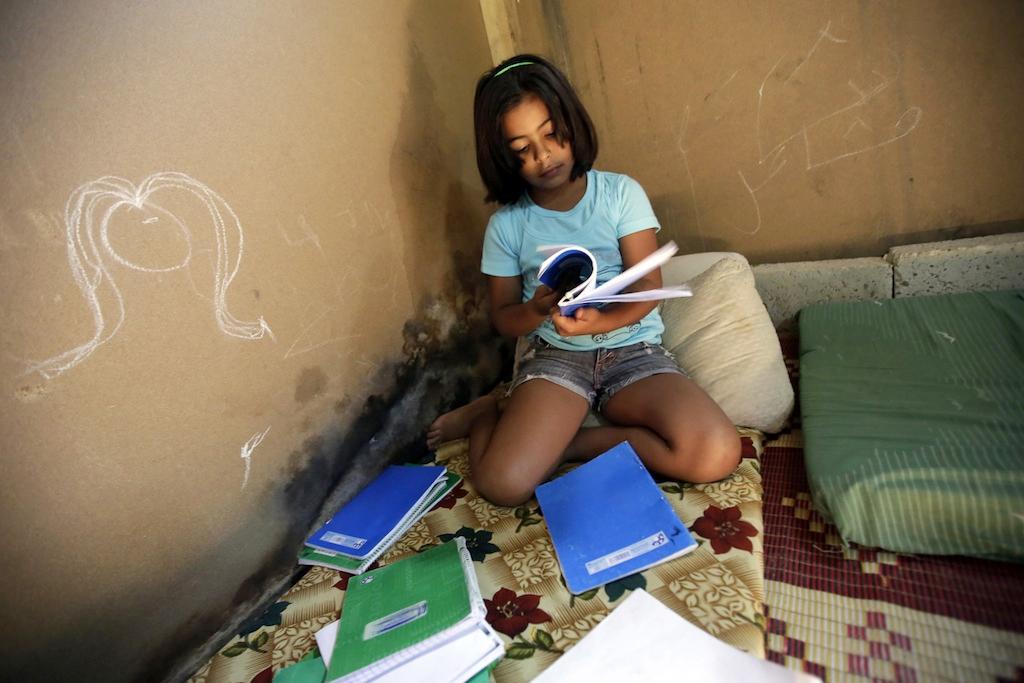

Syrian refugee girl Mashaael, 7, looks at an old exercise book as she waits inside her makeshift house before heading to school on September 26, 2013 in the northern Lebanese city of Tripoli. UN children agency UNICEF said 257,000 Syrian children were seeking education in Lebanon in 2013, a number that could rise up to 400,000 next year. Mashaael was not able to register at school as she didn’t meet the Lebanese public school system’s standards.

BERUIT — Nelson Mandela once said there can be no keener revelation of a society’s soul than the way in which it treats its children. When kids are living in school buses instead of riding them to school, it’s time to reevaluate.

Syrian refugee children are enduring an unimaginable crisis. Traumatized by war and separated from their families, they have little hope for the future.

Many of them watched as their families were killed and their homes destroyed in front of their eyes. They are forced to cope with the realities of war. They struggle to survive with economic and psychological hardships that even a grown adult would find overwhelming. To make matters worse, many are alone.

Unaccompanied Syrian children who have no parents face even longer odds of being registered, let alone attending a school.

I saw this harsh reality first hand during the five weeks I recently spent in Lebanon interviewing and surveying the living conditions of Syrian refugees as part of an assessment for Global Communities, a nonprofit organization that works to assist the vulnerable around the world.

The bulk of my time was spent in Beirut. I traveled often into the Mt Lebanon District—approximately 30 minutes outside of Beirut – which is the fastest growing district for the numbers of registered Syrian refugees in Lebanon.

After only two days of interviewing Syrian refugees, I was invited to an abandoned school bus that has become the home of Ahmad, a Syrian refugee from Homs. He escaped the fighting with his wife, disabled mother and two sons. After six months of waiting on the border between Lebanon and Syria, Ahmad and his family moved onwards to Beirut and found the bus next to a busy highway.

It has been their home ever since.

I asked Ahmad if his two children attended school. He shrugged his shoulders and said, ‘Keyf?’ How?

Like many other Syrian refugees, he was under the impression that he must pay an annual fee for school tuition of $60 per child. For a man living in a bus with no job and no savings, $120 is a hefty price.

He was surprised to learn that tuition payments along with access for uniforms, schoolbooks and transportation are services offered by humanitarian aid groups. But it is not only refugees who are unaware of this. School officials were also unaware of these services.

Despite the best efforts of numerous partners on the ground, Lebanon’s public education system is at a breaking point. The Lebanese Ministry of Education is working in conjunction with NGOs to accommodate the refugees, but it simply cannot take on the students.

300,000 Lebanese students and 30,000 Syrian refugee children are currently enrolled in public schools.

The Lebanese Ministry of Education and Higher Education recently agreed to increase the current schools' capacity by putting in place a “second shift” in 70 schools for the current school year, an initiative that provides seats for 210,000 Syrian children.

But that still leaves more than 200,000 Syrian children with no access to schools, and even if they are lucky enough to be enrolled in one, Arabic-speaking children are daunted by a language barrier since schools teach many classes in either French or English.

They face inadequate curriculum and severe overcrowding, and teachers are ill prepared.

What happens to these children?

Exploitation, child labor, early marriage, begging and crime are among the visible consequences resulting from leaving more than 200,000 children with no education. So many young people in a deteriorating economy creates widespread crime, as well as a breeding ground for recruitment into violent radical groups.

These avenues can seem like good choices for families desperate for money.

There are some simple fixes that could drastically improve conditions for refugee children. These include: establishing education outside the public school system and facilitating enrollment where children can learn, preferably from teachers within the refugee community; expanding and improving “second shift” schools that offer afternoon classes for youth who are not given access to schools in the morning, and coordinating a network of volunteers who go door to door to inform people that their children can go to school and help them navigate that process.

Even after the bullets stop flying and the explosions cease, Syria’s challenges will continue for years to come.

It will be a long and arduous process to restore any sense of normalcy to the country. It will involve healing the wounds of a generation of children scarred by war. Education is the bridge to moving forward and it must start now.

Lauren Pucci is a Humanitarian Assistance Officer specializing in emergency relief with Global Communities, a nonprofit organization that works to assist the vulnerable around the world.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!