Sunni and Shia divided in Iraq, the land of Cain and Abel

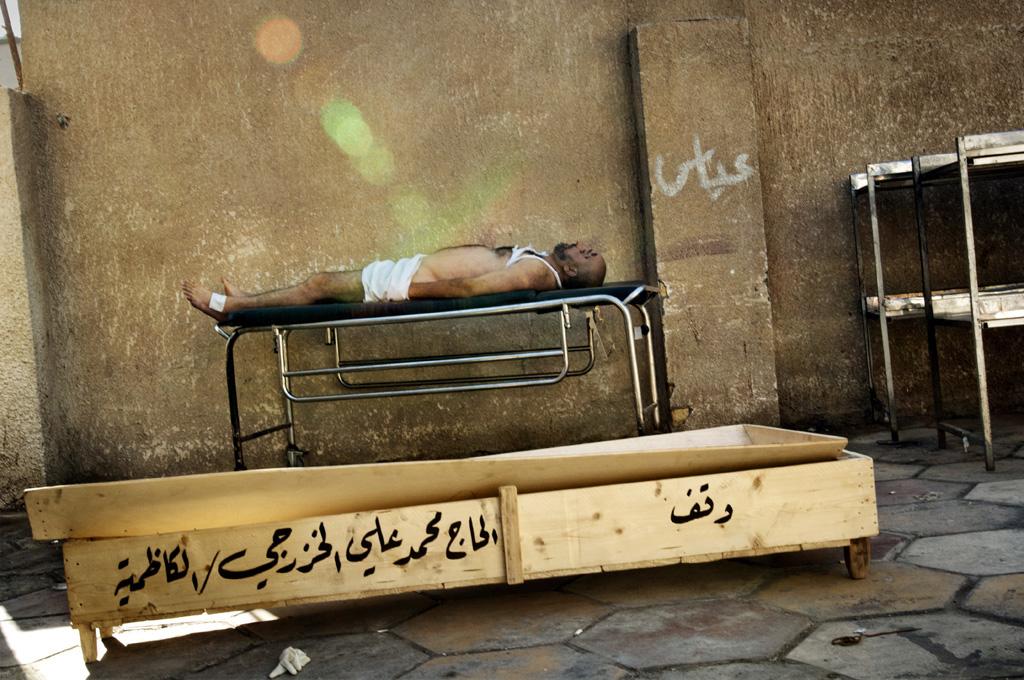

July 26, 2006 – A body rests on a gurney at the Yarmouk hospital morgue in Baghdad, Iraq. Parents make a pilgrimage here every day in search of lost relatives that have disappeared during the night. These photographs are a selection of Franco Pagetti’s work in Iraq over the last decade.

DAKUK, Iraq — In the rugged landscape of northern Iraq where biblical tradition holds that Cain killed Abel, the ancient fault lines of sectarian and ethnic conflict are laid bare.

There is no map that points to where the Old Testament story of Adam and Eve’s first-born son killing his brother might have taken place. The Bible says only that it lays ‘East of Eden.’ But 13th century historian Yacout al-Hamawi places it in the shadow of the Hamreen Mountains near this ancient town that would have been on the road from Babylon to Nineveh.

Today, in this same troubled land, the divisions that have wracked the region for centuries are coming to the surface. On the tenth anniversary of the US-led war in Iraq, the struggle for power is playing out not just in the halls of government and parliament but in the car-bomb factories and bank accounts that fuel sectarian attacks.

Some believe the seeds of the popular movements across the Arab world that have toppled dictatorial regimes were sown with the removal of Saddam Hussein from power. In Iraq, the demise of his iron-fisted dictatorship blew the lid off of suppressed sectarian conflict and opened the door to regional extremists.

In a country known for its relative religious tolerance, one of the biggest forces at play has become an ideology in which a tiny number of Sunni Muslims believe it is a religious duty to kill Shia Muslims. Those attacks by the Islamic State of Iraq are again increasing. Some believe the al-Qaeda front group is hijacking a growing protest movement by Sunni Iraqis who believe they have been displaced by the Shia’s historic rise to power.

In a culture in which neighbors refer to each other as brothers, the parables of Cain and Abel are still being played out in this ancient land of prophets.

![]()

Dozens of Jewish, Christian and Muslim prophets — major and minor — are believed to have been born and have died here. In Islam the split between Shia and Sunni over who should succeed the Prophet Muhammad was irrevocably deepened on the battlefield in Karbala with the killing of Imam Hussein.

In modern Iraq, sectarian divisions were cemented over by a socialist, pan-Arab Baath party. But it was the Shia, a minority in the region but a majority in Iraq, whose religion was suppressed. Saddam Hussein, who saw any competing allegiances as a threat to his power, banned public commemorations of Shia rituals and imprisoned and assassinated hundreds of clerics and deported thousands of Iraqi Shia.

With the fall of his regime, the tension came bubbling up to the surface, not just in Iraq but in a wary and hostile region. With the removal of Saddam Hussein, the Sunni Arab leaders who headed almost every country in the Middle East looked to Iraq and the specter of a swath of Shia-dominated territory with its roots in Iran.

“For the first time in the history of the region, the strongest dictator was removed from power,” said Iraqi historian Saad Eskander. “It changed the balance on many levels. One, the Shia-Sunni balance became an imbalance — for the first time Shia come to power by the virtue of a foreign invasion.”

Eskander believes the shock of Saddam Hussein being toppled is what allowed people in Tunisia, Egypt and other countries to imagine for the first time a life without dictatorship.

Dakuk was built on the ruins of a major city on the road from Babylon to Nineveh. It was leveled by an earthquake in antiquity and settled by Turkmen during the waves of Turkic migration starting more than 1,000 years ago.

The Turkmen, Iraq’s third-biggest ethnic group after Arabs and Kurds, are embroiled in a struggle for land and power in hundreds of miles of territory claimed by the Kurdish-controlled north and the central government. Just south of Kirkuk, the city was part of the region Saddam Hussein tried to Arabize, forcing Kurds and Turkmen to either list their identity as Arab or give up their homes.

“We don’t want to be part of the Kurdish territories. We either want to be independent or belong to the central government,” said Ali Jaffar, head of the local branch of the Iraqi Turkmen Front. He says they would be swallowed up by the more powerful Kurds.

The 70,000 residents of Dakuk, one of Iraq’s oldest Turkmen settlements, feel particularly vulnerable. Unlike most Iraqi Turkmen, they are Shia rather than Sunni Muslms.

Jaffar says they have no problem with their Arab and Kurdish neighbors. He says bombings in the town have come from further afield.

Six months ago, the local police station was blown up. In 2007, an attack on a Shia mosque killed more than a dozen people. Nearby Tuz Kharmato, another Shia Turkmen city, has suffered more than seven attacks in the last six months.

“The terrorists come from Mosul and Diyala,” says Jaffar, referring to the mostly Sunni Arab city and province in north-central Iraq. “If there are problems they are coming from outside.”

Pictures of martyrs, all of them Shia, who were killed in the civil war between 2006 and 2008. |

At the main Husseiniya, the Shia place of worship, the photos of 19 victims of a car bombing in 2007 hang on the wall, seven of them from one family. Six months ago, six policemen were killed when the police station was bombed. The attacks were blamed on the Islamic State of Iraq, al-Qaeda in Iraq’s front group. Shia places of worship and Iraqi security forces are its main targets.

Shia Muslims are believed to make up about 60 percent of the Iraqi population with Sunnis — both Arabs and Kurds — another 35 percent. There is a small Christian minority in Iraq as well. A disproportionate percentage of Iraqis who fled the country after 2003 and during the sectarian violence are Sunni or Christian, according to refugee officials. The exodus leaves Shia Iraqis making up even more of a percentage of the population in Iraq.

As al-Qaeda and its allies re-emerge in Iraq, attacks against Shia are increasing. Officials say Sunni extremists are emboldened by the Syrian conflict just across the border, which threatens to spill across the region.

“This is what we have been warning,” said a senior Iraqi official. “That the Syrian crisis will end up in a sharp sectarian division in the region….The crisis is reaching us and the effects are getting here much sooner than we expected.”

The official, who asked to remain anonymous to be able to speak more candidly, said the fall of some Syrian towns along with border to opposition fighters was fueling a three-month-old protest movement in Iraq’s Sunni provinces.

He said Iraq’s Shia leaders fear that if Bashar al-Assad falls to Sunni-led forces, they could be next.

“The government is worried about the possibility of a Sunni -Shia confrontation because after Syria is done there are those within the Shia political elite in this country who think they will try to unseat the Shia government here.,” the official said. “That is why there is hyper-tension here. Everything is interpreted in these sectarian terms.”

The protests started in December in Fallujah and Ramadi with the arrest of Sunni Finance Minister Rafi al-Assawi’s bodyguards on terrorism charges. While not exclusively Sunni grievances, their demands reflect a belief by Sunni Arabs that they have suffered a decade of discrimination.

The protests now draw hundreds of thousands of men after Friday prayers in Sunni cities and neighborhoods. Their demands began with calling for reform of anti-terrorism laws that have jailed tens of thousands of Iraqis without charge and for laws aimed at punishing former Baath party loyalists. Even Iraqi officials acknowledge that both laws disproportionately affect Sunnis.

In recent weeks, the demands have changed to toppling Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki’s government. And as the rhetoric becomes more sectarian, many of the Shia figures who originally backed their demands have pulled their support.

“There was a lot of sympathy from the Marjaiya (Shia religious scholars) and Muqtada Sadr and the southern provinces in the beginning but obviously once it turned sectarian, it would not get the sympathy that it got at the beginning,” said Maysoon Demaluji, a member of parliament from the mainly Sunni Iraqiya bloc.

“Still,” she said, “people have genuine grievances regardless of what people say at podiums.”

What happens in Iraq’s sectarian conflict depends largely on who takes power in Syria, according to analysts and officials in the region. Many say al-Maliki has resisted wider reforms that could ease sectarian tensions with Iraq’s increasingly fearful Sunni population.

Sunni politicians belatedly entered Iraq’s post-war politics — boycotting the first elections. In the 2010 elections, Iraqiya candidate Ayad Allawi won more seats than Nouri al-Maliki but not enough to govern by himself. Allawi eventually threw his support behind a coalition headed by al-Maliki with the assumption that they would share power. The power-sharing never happened.

At Sunni protests, new, more radical leaders appear to be emerging. They have condemned their own politicians as too moderate and threatened to challenge the Iraqi government by marching to Baghdad.

“It’s impossible to tell who represents these people,” said the senior Iraqi official. “You’ve seen what happened to their political leaders. There are new leaders — tribal and religious. No one knows who they represent.”

Some members of Maliki’s political bloc believe the government faces a greater threat than it did during Iraq’s sectarian war when al-Qaeda in Iraq and Shia militias fought for control with Iraqi security forces.

“In 2006 and 2007 al-Qaeda was acting as individuals doing explosions and killing people but now they want to give it a popular peaceful cover,” said Kamal al-Sa’edi, a member of parliament in Maliki’s State of Law. “That is why they planned the idea of marching to Baghdad.”

“The Sunnis consider it a historic right to rule,” said al-Sa’edi. “They believe that power in the hands of the Shia and the Kurds violates such a historic right.”

The main commercial street in Baghdad. Where there were once posters and statues of Saddam Hussein, there are now symbols of the dominant Shia community. |

Baghdad, once a walled city, is again becoming a fortress. More concrete blast barriers have gone up around parliament as protection from car bomb blasts. Iraqi officials have announced that a recent series of car bombs detonated in Baghdad were assembled in Fallujah. After threats to take the protests to Baghdad from al-Anbar and other provinces over the last few weeks, the Iraqi government not only made clear it would ban such protests, it set up army roadblocks to physically prevent them.

The Iraqi army pulled out of Fallujah after shooting dead seven protesters in February), leaving the federal police to secure the city. The provincial capital Ramadi has become its own city-state.

“Everything is in a state of flux. This is the dangerous thing,” said Eskander. “Those who want the victimizers to come to power and forget the past don’t realize you cannot forget the past. And on the Shia side, not everything should be about revenge — part of it is reconstruction and reconciliation.”

Before the Syria crisis, Iraq was just beginning to emerge from a decade of regional isolation that linked the Shia-led government with the US invasion of Iraq. Baghdad hosted a historic Arab League summit last year after repairing relations even with Kuwait, invaded by Saddam Hussein in 1990.

The Iraqi government’s opposition, though, to a military overthrow of Bashar al-Assad has put it sharply at odds with Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Turkey, an emerging regional power. While sectarian sentiment is still on the surface of everyday life, it seems to have embedded itself into Iraq’s political culture.

“Some of the statements I hear are shocking — they cannot contemplate that they will be able to live together again,” says an Arab political analyst with long experience in Iraq.

“The Sunni Arab community dealt with the invasion of Iraq as a big loss. It was a shock for them, an identity crisis,” said the analyst. “This was a community that shaped Iraq in its own image and now they stand to lose everything. Who do you have coming from outside? Either Kurds or Shia who throughout the years, because of the grievances that were accumulated, developed a sharper sense of communal identity at the same time.”

Under Saddam Hussein’s Baath party, tens of thousands of Shia were exiled, many of them deported to Iran. In 1991 when the US drove Iraq out of Kuwait and encouraged Shia and Sunnis to rise up against Saddam Hussein, Iraqi forces slaughtered thousands of people in Shia areas, most of them civilians.

“There is an underlying trend of revenge,” says the analyst, who asked to remain anonymous to be able to speak freely about Iraqi government policies after 2003. “Nobody was talking about it but many of the things that were taking place somehow to me reeked of revenge and fear — they wanted to make sure that what happened to them never happened again.”

Many Iraqis fear that their country is becoming more polarized.

At the Um al-Tabul mosque in Baghdad’s Qadissiyah neighborhood, Shiekh Mahdi al-Sumadaie opened a historic copy of the Koran he says was damaged by US forces in 2003. Sumadaie, a Salafi cleric, spent five years in US detention for advocating attacks on US forces. He has now distanced himself from al-Qaeda figures he defended as launching legitimate resistance against occupation.

These days, he fears attack not from government forces but from former followers who see him as too moderate.

Shaik Medhi al-Sumadaie, a cleric who was jailed for five years by US forces for encouraging an attack on American forces. During his detention his wife was killed at a US forces checkpoint. |

“They call me the living martyr,” said the cleric. “It’s because I have adopted moderation…My experience tells me that force and bloodshed do not work…This is why for the protestors, I should be killed because I have not joined the protests.”

There were only a few dozen people in the mosque for al-Sumadaie’s Friday sermon. Many of his normal followers had joined a protest at mass prayers with a more fiery cleric.

Many Sunnis and Shia believe that the violence raging in neighboring Syria and the prospect of a wider conflict are signs of impending judgment day.

“I always say that if society does not follow God, rivers of blood would be opened,” said the cleric after a sermon in which he warned of a prophesied beast rising from the ground. “This is part of the signs of judgment day, widespread chaos and killing. We believe that the signs of judgment day are very close.”

Al-Sumadaie said he believes Iraq’s sectarian tension was politically driven.

“It is a sectarian conflict being led by politicians,” he said. “Many Shia and Sunnis reject it, but it is a political sectarian conflict.”

“Syria is prompting sectarian tension not only in Iraq but against other countries,” said Dhia al-Assadi, secretary general of cleric Muqtada Sadr’s al-Ahrar bloc in parliament. “We’ve stated clearly we’re not against the change in regime in Syria, we’re against the taking over of extremist powers…That’s why we said it is better keeping Bashar’s regime, because it was not really promulgating sectarianism or extremist discourse, than bringing a government run by Salafis or a new version of the Taliban or al-Qaeda. No one can guarantee that the replacement will be better.”

Al-Assadi is part of the new face of a Sadr party, which he says has changed after the departure of US forces, renouncing violence and redrawing the definition of Iraq’s Shia-dominated politics by joining forces with Kurdish and Sunni parties.

“We believe that Iraq should not be governed by any ethnic or religious group,” said al-Assadi. “This is what couldn’t be understood by our partners — they thought we are trying to destroy this Shia coalition.”

Al-Assadi said Sadr’s recent overtures to the Kurds were proof that in a country where almost every party is tied to a foreign country, the Sadrists have carved out positions independent of Iran.

“I think he doesn’t listen very much to the Iranians. He took most of his decisions against the Iranian will, particularly when he visited Erbil and he joined Iraqiya and the Kurds in withdrawing confidence in Prime Minister Maliki — that was totally against Iranian interests in Iraq because they supported al-Maliki.”

Government officials reject suggestions that the country could be plunged back into civil war.

“If you look at the ultimate goal of such acts you will find it is to trigger a sectarian war and that all acts are done professionally,” said Ali al-Mussawi, an advisor to the Iraqi prime minister. “This side is neither Shia nor Sunni, it’s al-Qaeda and its agendas…Everyone understands it is not the Sunni brothers or the Shia brothers who are doing it.”

The Sunni-Shia split is just one of several conflicts playing out in Iraq and the region, where Iran, Turkey and Russia are among the non-Arab players vying for influence.

“It’s more than Sunni-Shia,” said Eskander. “This is a conflict between the center and the provinces. It’s a conflict within each community, within each coalition. It’s a conflict between different generations and it’s a conflict as an extension of conflicts in the region. Sometimes they are fighting on behalf of certain forces.”

Despite the clear evidence of rising ethnic and sectarian conflict, there are many here, particularly in towns like Dakuk, who also remember the long tradition of coexistence.

The land that marks the biblical tale of Cain and Abel may stand as a stark reminder in a barren landscape of brother killing brother.

But at Dakuk’s more concrete site of remembrance, Shia and Sunni Iraqis have co-existed literally for centuries in keeping alive belief in their shared faith.

On a hilltop overlooking rocky fields, dozens of families came on a recent afternoon to pray at a shrine dedicated to Ali Zein al-Abideen al-Sajid, the only son of Imam Hussein to have survived the battle of Karbala. He and the women in Imam Hussein’s family were believed to have rested at the site while being taken as prisoners to Damascus.

On a recent day, Sekena Abdul Qader and her family cooked a sheep as they have in gratitude every year for the last thirty years, since their uncle was given a job they had prayed for at the shrine. They distributed the mutton and broth poured over dried bread to visitors.

Abdul Qader said Imam Zain al-Abideen makes no distinction in granting prayers except that of traditional Arab hospitality.

“Sunnis will get their prayers granted even faster because they are guests,” she says. “We are part of his family.”

This story is presented by The GroundTruth Project.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!