Shia Muslims in Saudi Arabia keep the protest movement alive

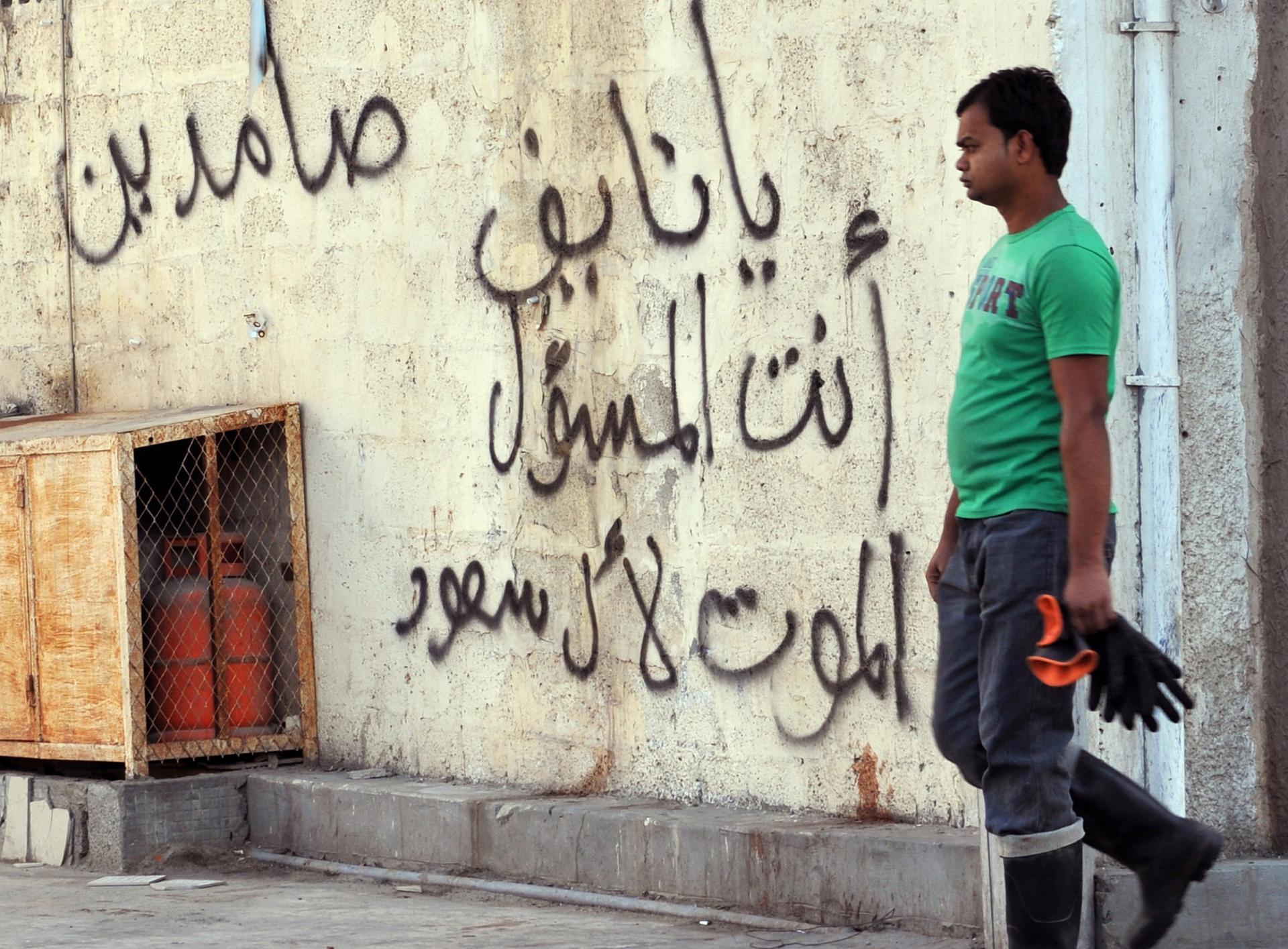

A foreign worker walks past graffiti against the ruling Saudi royal family in the mostly Shia Qatif region of Eastern Province on November 25, 2011. Four people have been killed and nine others wounded in an exchange of gunfire between security forces and what the Saudi interior ministry called criminals serving a foreign power in the country’s oil-producing Eastern Province.

Editor’s Note: When Arab Spring protests broke out in Saudi Arabia in 2011, the government reacted quickly. It pumped $130 billion into the economy, including hiring 300,000 new state workers and raising salaries. It also brutally cracked down on dissent, in some cases breaking up peaceful protests with live ammunition. While the carrot and stick approach worked in some cities, the Shia Muslims in the Eastern Province continued to protest. Shia make up some 10-15 percent of the Saudi population and have long rebelled against discrimination and political exclusion.

Demonstrations continued in the city of Qatif but got little publicity because foreign journalists are banned from reporting there. Correspondent Reese Erlich, on assignment for GlobalPost and NPR, managed to get into Qatif, meet with protest leaders and become the first foreign journalist to witness the current demonstrations. This is his account:

QATIF, Saudi Arabia — Night has fallen as the car rumbles down back roads to avoid the Saudi Army’s special anti-riot units. To be stopped at any of the numerous checkpoints leading into Qatif, would mean police detention for a Western journalist and far worse for the Saudi activists in the car. They would likely spend a lot of time in jail for spreading what Saudi authorities deem “propaganda” to the foreign media.

In Saudi Arabia all demonstrations are illegal, but here in Qatif residents have defied the ban for many months. At least once a week the mostly young demonstrators march down a street renamed “Revolution Road,” calling for the release of political prisoners and for democratic rights.

The anti-riot units deploy armored vehicles at strategic locations downtown. The word on this night is that if demonstrators stay off the main road, the troops may not attack.

Foreign journalists are generally denied permission to report from Qatif. Activists said this night was the first time a foreign journalist has been an eyewitness to one of their demonstrations. Asked if the troops will use tear gas, Abu Mohammad, the pseudonym used by an activist to prevent government retaliation, says, “Oh, no. The army either does nothing or uses live ammunition.”

I really hope it will be option #1.

Suddenly, young Shia Muslim men wearing balaclavas appear, directing traffic away from Revolution Road. All the motorists obey the gesticulations of these self-appointed traffic cops.

Minutes later several hundred men march down the street, most with their faces covered to avoid police identification. Shia women wearing black chadors, which also hide their faces, follow closely behind, chanting even louder than the men.

One of their banners reads, “For 100 years we have lived in fear, injustice, and intimidation.”

Despite two years of repression by the Saudi royal family, Shia protests against the government have continued here in the Eastern Province. Though Shia are a small fraction of Saudi Arabia’s 27 million people, they are the majority here. Most of the country’s 14 oil fields are located in the Eastern Province, making it of strategic importance to the government.

The Story Behind the Story: Reese Erlich on reporting in Saudi Arabia

![]()

Shia have protested against discrimination and for political rights for decades. But the Arab Spring uprisings of 2011 gave new impetus to the movement. Saudi Arabia is home to two of Islam’s most holy cities, and the government sees itself as a protector of the faith. But its political alliances with the US and conservative, Sunni monarchies have angered many other Muslims, including the arc of Shia stretching from Iran to Lebanon.

Saudi officials claim they are under attack from Shia Iran and have cracked down hard on domestic dissent.

Saudi authorities are responsible for the death of 15 people and 60 injured since February 2011, according to Waleed Sulais of the Adala Center for Human Rights, the leading human rights group in the Eastern Province. He says 179 detainees remain in jail, including 19 children under the age of 18.

The government finds new ways to stifle dissent, according to Sulais. Several months ago the government required all mobile phone users to register their SIM cards, which means text messaging about demonstrations is no longer anonymous.

Abu Zaki, another activist requesting anonymity, says demonstrators now rely on Facebook and Twitter, along with good old word of mouth. Practically everyone at the recent Qatif protest march carried iPhones. Some broadcast the demo in near real time by uploading to YouTube.

Organizers hope their sheer numbers, along with government incompetence, will keep them from being discovered. “The government cannot follow everybody’s Twitter user name,” says Abu Zaki. “The authorities have to be selective and, hopefully, they don’t select my name.”

When protests began, demonstrators called for reforms. But now, younger militants demand elimination of the monarchy and an end to the US policy of supporting the dictatorial king.

Abu Mohammad, Abu Zaki and several other militant activists, gather in an apartment in Awamiyah, a poor, Shia village neighboring Qatif. In this part of the world a village is really a small town, usually abutting a larger city. Awamiyah is one such town, chock full of auto repair shops, one-room storefronts, and potholed streets. It is noticeably poorer than Sunni towns of comparable size.

Strong, black tea is served along with weak, greenish Saudi coffee. The protest movement in Qatif, they observe, resembles the tea more than the coffee.

Abu Mohammad tells me protests have remained strong because residents are fighting for both political rights as Saudis, and against religious/social discrimination as Shia.

Shia face discrimination in jobs, housing and religious practices. Dammam, the largest city in the area, has no Shia cemetery, for example. Only six Shia sit on the country’s 150-member Shura Council, the appointed legislature that advises the king.

“As Shia, we can’t get jobs in the military,” says Abu Mohammad. “And we face the same political repression as all Saudis. We live under an absolute monarchy that gives us no rights and steals the wealth of the country.”

The government denies those claims of discrimination and repression. In Riyadh, Major General Mansour Al Turki, spokesperson for the Ministry of Interior, is the point man who often meets with foreign journalists. Al Turki is smooth and affable and practiced at the art of being interviewed by Westerners.

He dismisses Shia charges of discrimination as simply untrue.

“These people making demonstrations are very few,” he tells me. “They only represent themselves. The majority [of Shia] are living at a very high level.”

Such assertions, however, don’t account for the frequent and sizable Eastern Province demonstrations supporting Sheik Nemer al Nemer. The charismatic Shia cleric has long been a thorn in the government’s side. His willingness to speak out against discrimination and call for militant action endeared him to the younger generation of activists. For months he avoided arrest by shifting residences and only appearing in public during large rallies.

Then in July 2012 authorities made an arrest while he was briefly visiting his house in Qatif. He was shot and seriously wounded. Police claim it was an armed shootout in which they fired in self defense.

The Sheik was unarmed, according to his brother, Mohammad al Nemer. He says his brother hasn’t been publicly charged, but has been told that he faces a long jail term for instigating unrest against the king and organizing illegal demonstrations.

Four police bullets shattered his brother’s thigh bone, says al Nimer. “If he doesn't receive proper medical care, he will have a lame leg for the rest of his life.”

Al Nemer’s popularity has grown exponentially since his arrest, with graffiti demanding his release sprouting up throughout the area and marchers regularly chanting his name.

Shia leader Sheik Mohammed Hassan al Habib offers understanding of the continuing protests. The cleric lives in a modest home on a side street outside Qatif. Sheik al Habib adds something special to the usual proffering of tea and coffee: Swiss chocolate.

Al Habib tells me that the Eastern Province movement seeks democratic reforms while maintaining the power of the monarchy.

“We need to give real power to the parliament,” he says. “The government should allow establishment of political parties, freedom of speech and assembly.” But the king would still have final authority, he concedes.

“We don’t want toppling or removal of the regime,” he emphasizes.

He acknowledges, however, that many younger protestors have given up on reform. For example, activist Abu Mohammad says, “People now want the overthrow of the ruling family as a reaction to the escalation of repression in Qatif. I think the best form of government for Saudi Arabia is constitutional monarchy like they have in Britain.”

While calling for a UK-style constitutional monarchy is rather tame by western standards, it’s treasonous in Saudi Arabia.

“People must complain through the legal process,” argues the Ministry of Interior’s al Turki. The legal process does not include calling for an end to the monarchy.

Al Turki adds that the opposition is controlled by Iran and seeks to establish a Shia Muslim dictatorship. The Iranian government does “affect such people,” he says. “But its influence is very limited.”

Al Habib denies the movement is directed from Iran. In fact, he criticizes the Iranian government for its treatment of demonstrators demanding democracy after the 2009 presidential elections.

“I was in Iran in 2009,” he says. “That was their legitimate right to demonstrate. The Iranian government should not have repressed them.”

But the “Iranian threat” remains a cornerstone of Saudi policy, justifying, for example, sending Saudi troops to neighboring Bahrain in March 2011 to help put down that country’s indigenous, Arab Spring uprising. It also justifies massive US military sales to the Saudi armed forces.

Because of oil riches, Saudi Arabia’s ruling family has been a high priority for US presidents dating back to Franklin Roosevelt. The US sent its first military mission to the kingdom in 1943 and began training Saudi troops in 1953. The US built up Saudi Arabia’s military as part of Cold War competition with the USSR. Saudi Arabia provided a steady flow of oil to the west; the US didn’t interfere with the royal family’s internal repression.

In recent times, Saudi Arabia has allowed the US to establish a drone base on Saudi territory, and it continues to receive massive US military aid.

In 2010, the US Congress passed legislation calling for $60 billion in military aid to the Saudis over 10 years. In 2011, the Obama administration allocated $30 billion of that to purchase US-made, advanced fighter jets and other hi-tech equipment.

Saudi Arabia spends 10 percent of its Gross Domestic Product on the military, ranking it third highest in the world on a per capita basis. Both US and Saudi leaders argue that such aid allows the kingdom to defend itself from outside attack.

Speaking of the $30 billion package, Andrew J. Shapiro, assistant secretary of state for political-military affairs, says the sales would “enhance Saudi Arabia’s ability to deter and defend against external threats to its sovereignty.”

Unfortunately, Saudi armed forces have not proven to be adept at such defense. When Iraq invaded nearby Kuwait in 1990, the Saudi military was virtually helpless in defending itself against the perceived threat. The US and European allies fought the Gulf War while the Saudis footed the bill.

Saudi Arabia’s arms have proven effective, however, in quelling domestic dissent. In response to the repression, the State Department report on human rights offers a pro forma list of “reported” problems in Saudi Arabia. “The most important human rights problems reported included citizens’ lack of the right and legal means to change their government….”

Activists sharply disagree with US support for the royal family, pointing to the difference between US stands on Syria and Saudi Arabia.

“America supports the royal family because they protect its interests,” says Abu Zaki. “The pressure is growing. People are getting angrier and angrier” at US policy.

The Saudi royal family used a combination of repression and economic improvements to quell protests that broke out around the country in 2011. Authorities announced a $130 billion spending program that would hire 300,000 more state workers, raise salaries, and build subsidized housing.

But neither government spending nor harsh crackdown have so far deterred the protesters in Qatif.

The demonstrators see themselves waging a political battle in which popular support can overcome the government’s repressive apparatus. The Shia of the Eastern Province are the only Saudis regularly holding protest marches, but as Shia cleric Al Habib tells me, Sunnis in other parts of the country also call for reform.

“We work with reformers who don’t care about your sect,” he tells me. “They look only for reforms. We hope Sunni and Shia will get together one day to pursue this goal.”

After a sip of black tea and a final piece of chocolate, we say goodbye to the cleric and head out to that night’s demonstration. Somehow we manage to avoid the checkpoints. And for that night, at least, there was no violence.

Freelance journalist Reese Erlich’s reports from Saudi Arabia and Bahrain are part of a GlobalPost Special Report on the role of the Sunni/Shia rift in Middle Eastern geopolitics, in partnership with NPR.

This story is presented by The GroundTruth Project.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!