‘Once and for all’: Women are essential to global stability

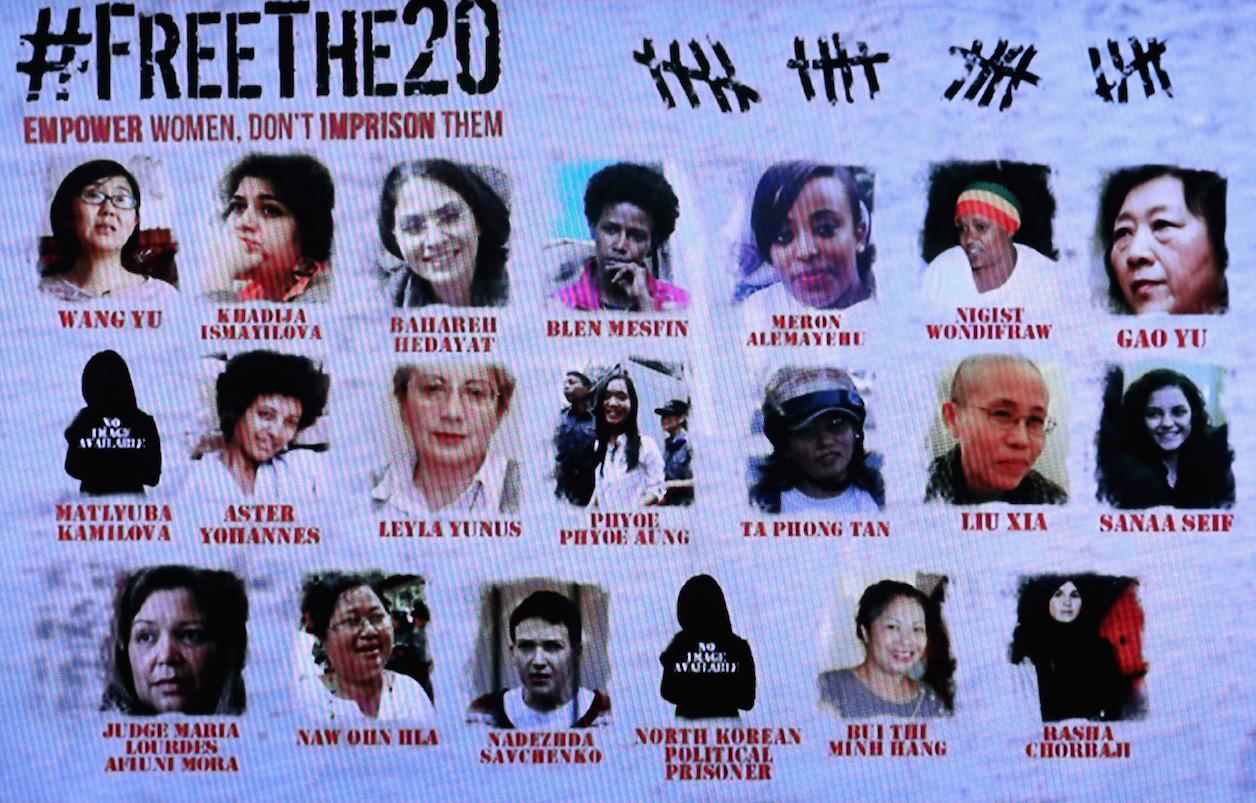

To mark the 20th anniversary of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, the US Mission to the UN profiled 20 women political prisoners and other prisoners of concern from around the world in September 2015.

By Swanee Hunt

Fall 1995. First Lady Hillary Clinton shrugged off objections from United Nations-bashers, congressional Republicans, and State Department officials nervous about relations with China. As honorary chair of the US delegation, she insisted on addressing the UN’s Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing.

As backdrop to the controversy, defense experts were probing flaws in Cold War policies designed to ensure the inviolability of a nation-state’s borders, instead of the well-being of its people. This was the First Lady’s chance to lean into that global debate.

“Human rights are women’s rights, and women’s rights are human rights, once and for all,” Clinton famously declared. Her catalytic speech lent fuel to a movement resulting in the landmark UN Security Council Resolution 1325, adopted 15 years ago this month. It makes clear: A greater role for women is essential to global stability.

Some assume that Americans’ more realistic conception of security emerged in 2001, from terrorist attacks on 9/11. That’s short-sighted by at least six years. The Beijing conference directly fostered the more effective paradigm that has emerged in the 20 years since. This doctrine — inclusive security — insists that it’s necessary to have a range of stakeholders, particularly women, at the table to quell violent conflict and build lasting peace. The idea has proved transformative, smashing open zero-sum thinking about how to prevent the suffering caused by war.

A road paved with good intentions

Leadership at the 1995 conference — and at a parallel nongovernmental forum that drew 30,000 people two hours away down a muddy, rutted road — came from the "global south" as well as Western delegations. Attendees included survivors of the 1994 Rwandan genocide, in which nearly a million of the country’s eight million people were killed in 100 days. Oppressed Dalit women in Nepal and India were speaking out that September. Bosnians arrived, even as the three-year war raged at home. The presence of these unvanquished heroes trained a powerful spotlight on women and war.

The culminating Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action was forcefully clear: “Equal participation in decision-making is not only a demand for simple justice or democracy but … a necessary condition for women’s interests to be taken into account. … Without the active participation of women and the incorporation of women’s perspective at all levels of decision-making, the goals of equality, development and peace cannot be achieved.”

Conflicting signals

Debates were both practical and academic as NATO undertook its first-ever military operation, to counter the horrific suffering in the Balkans. Concurrently, two American thinkers were constructing security concepts for a post-Cold War world. At Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, dialectic emerged. In his 1996 "Clash of Civilizations," Professor Samuel Huntington asserted that “the great divisions among humankind and the dominating source of conflict will be cultural.” He counseled figurative walls along what he saw as ideological fault lines, particularly between Muslim and non-Muslim nations.

Joseph Nye, a once-and-future senior US government official, took a contrasting view. Since the 1970s, Nye’s vision had encompassed a complex, interdependent world; now he took the next logical step, framing the need not solely for military force but, whenever possible, diplomacy and persuasion. Dean Nye’s 1997 decision to create a Women and Public Policy Program at Harvard grew out of that worldview.

The “clash” doctrine, while simple to grasp, failed to hold up in contemporaneous conflicts: Bosnian Muslims looked west for support against Orthodox Christian Serb aggressors, who looked east to their Russian cousins. Nye’s “soft power” paradigm, combining military action only as backup to attraction and alliances, would be measured by a true-to-life yardstick described to me by a Kenyan parent: “What does it matter if my child is killed by a bullet, starves, or is gang-raped coming home from school and contracts AIDS? She’s dead.”

A new map: Inclusion

Nye’s thinking was buttressed by business and social science research — well accepted now, two decades later — that demonstrates the value of “typically feminine” persuasive skills. Gender diversity in problem-solving leads to measurably quicker success.

Parallel qualitative data abound on women working across lines of conflict, often mediating to re-open schools or provide food and medical help. In Liberia, Christian and Muslim women banded together to force male warlords to compromise, ending the 2003 civil war — and earning the Nobel Peace Prize.

A decade later, Christian pastor Esther Ibanga formed the Women Without Walls Initiative in Nigeria, combating ethno-religious murders and kidnappings by Boko Haram. Ibanga reached out to a respected Muslim woman to form an interfaith movement, capitalizing on a strategic advantage: Women often have access denied men, who are seen as more threatening because they’re usually the perpetrators of violence. From Colombia to Cambodia, Kosovo to Congo, women have bridged conflicts with “the other camp” when men would have been barred or killed.

Including women also improves traditional, but fraying, security structures: Adding females to Pakistani police forces means women are more willing to report crimes, security sector reform is better executed, and the reintegration of ex-combatants is more effective. In short, including women in security organs and policy creation makes a society more livable, whether measured by the rate of employment, public safety, or by access to food and clean water.

This evidence has brought the doctrine of inclusive security new adherents, some surprising. Its champions include political leaders, among them Afghan President Ashraf Ghani, who has vowed — despite formidable opposition — to increase the number of women in parliament and working as government ministers and ambassadors. Eminent academics such as Harvard’s Steven Pinker are exploring how increasing “feminization” (including empathy, among other “better angels”) leads to decreasing violence. Defense officials in various commands are recruiting female troops and removing barriers to their promotion.

On Oct. 31, 2000, five years after the conference in China, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 1325, the defining agreement in the field of women, peace, and security. The proclamation was designed to address not only the disproportionate impact of war on women, but also the pivotal role they can play in sustaining peace. While 1325 was initially supported more in theory than practice, a pragmatic follow-up declaration urged each country to develop a comprehensive national strategy to implement the resolution’s goals.

Some 55 countries have launched national action plans, and others are in the pipeline. Several have already revised their initial designs, with sturdier methods to evaluate progress. UN Women’s special fund for developing these approaches can’t keep up with demand, nor can the Washington-based Institute for Inclusive Security, which provides in-depth expertise to countries forming or improving their blueprints (Editor's note: The author chairs this institute).

The enormity of the task cannot be overstated. An effective strategy knits together hundreds of government actors, to draft, implement, measure, and monitor; it took the Afghan government three years to coordinate 15 ministries before the recent launch of its national action plan. Civil society organizing is equally demanding, requiring zealous input from activists, businesspeople, educators, and media professionals. But weaving wisdom from experts inside and outside government is what makes the best strategies effective.

Moving forward

Given well-known champions, effective strategies, and solid evidence that inclusion is an advantage, what’s the roadblock?

One sadly ironic obstacle is the laudable desire to shield the vulnerable. Women and girls clearly suffer disproportionately from wartime sexual assault, but well-meaning officials conflate general helplessness with the need for protection from targeted violence. “Women and children first!” seems civilized. But the lens of victimhood obscures competence. Patronizing is perilous, even when stemming from an honest desire to defend. Less altruistically, given political and economic interests, it’s just hard to concede power.

The impetus toward a new paradigm is being driven by both ground-level actors and a new generation of policymakers. Norwegian Minister of Defense Ine Eriksen Søreide explained in 2014 why “strong security needs to be inclusive security… From a military and defense policy perspective, the 1325 agenda is not primarily about gender equality…[but] capability and operational effectiveness.”

Military leaders are grappling with lessons from improved performances of NATO special operations forces when “female engagement teams” were added to all-male units in Afghanistan. Jordan, a NATO partner, is taking the lead in analyzing how to better integrate women into armed forces. Similarly, the 2014 US Congress authorized funding to advance women in police forces throughout Central and South Asia.

On the nongovernmental side, female leaders are primed with lessons from the past two decades. In China, Irene Santiago of the Philippines headed the enormous NGO Forum; two decades later, she is internationally acclaimed for helping negotiate a ceasefire in Mindanao and is still organizing civil society to be sure the prevailing security model is inclusive. In Beijing, she stood with Rwandans, Bosnians, Americans, and others to force the issue of women’s inclusion. Today Yemen, South Sudan, Canada, and Brazil continue the drive toward a saner world.

At a Kennedy School meeting in 2006, then-professor Ashton Carter told colleagues that the doctrine of inclusive security emerging there was “ahead of its time.” The secretary of defense will be glad to know: The time has arrived.

Swanee Hunt is founder and chair of the Institute for Inclusive Security; former US ambassador to Austria; and founder of the Women and Public Policy Program and the Eleanor Roosevelt Lecturer in Public Policy at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!