Mexican drug cartels are expanding their reach in Peru

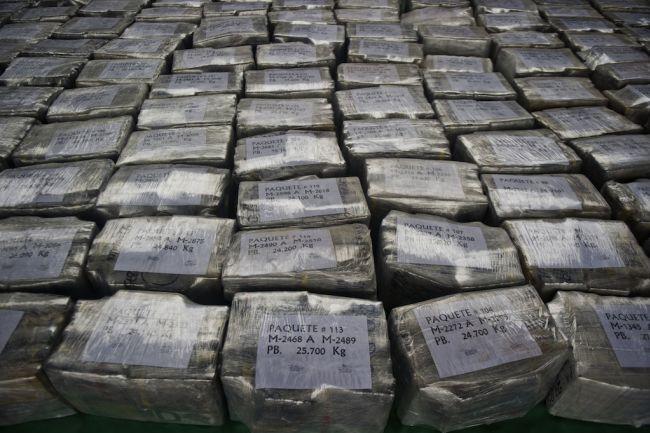

Peru seized more than 7 tons of cocaine late August.

LIMA, Peru — When police here unearthed nearly 8 tons of cocaine — a national record — hidden inside lumps of coal late last month, it was little surprise that two Mexican citizens were also arrested.

The brutal Mexican cartels that control the drug routes from remote Andean villages where raw coca plants grow to the world’s largest consumer market, the United States, are known to have been present in Peru since the 1990s.

Nevertheless, the haul found in a small seafront warehouse in Huanchaco, a fishing village known for its surfing on Peru’s northern coast, stood out for another reason: It was bound not for the US but, in two separate shipments, for Spain and Belgium.

“What is surprising is that this implies a change in the criminal map,” said Peru’s former anti-drug czar Ricardo Soberon. “For Mexicans to be running drugs from Peru to Europe, without it ever going anywhere near Mexico — wow!”

There may be little mystery about the Mexicans’ motivations, which appear rooted in basic economics.

“The European market is more profitable than the American market,” notes Flavio Mirella, the head of the Peru branch of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. “Demand pushes supply.”

That is largely a reflection of street prices. One gram of cocaine in Europe cost on average $191 in 2010, according to Mirella’s agency, compared to $169 in the US.

More from GlobalPost: Ecuador, cocaine’s stopover on the way to market

Little has been revealed about the two Mexicans arrested, beyond their names, Ruben Larios Cabadas and Jhoseth Gutierrez Leon. Police say they are suspected members of Mexico’s Sinaloa cartel, in Peru to oversee the European shipments by two companies, Carboniferas Alfa & Omega and Betas Andinas del Peru.

![]() Peruvian authorities hauled off eight detainees. Cris Bouroncle/AFP/Getty Images

Peruvian authorities hauled off eight detainees. Cris Bouroncle/AFP/Getty Images

The pair, along with six Peruvians who were also arrested, is now being questioned in Lima. Peruvian police have also asked their Mexican counterparts for information about the alleged boss of the operation, Lee Rodriguez, known as “El Duro,” or “the tough one.”

Both companies were founded in 2011 with a total initial capital of around 60,000 soles (roughly $21,000) and are thought to have realized 30 shipments of coal to Europe since then.

At least some of those would have been without cocaine, as the traffickers sought to evade detection and make their venture appear legitimate.

But Soberon speculates that around 20 would have contained cocaine. Assuming they each involved similar amounts of drugs as the intercepted shipments, then, doing some back-of-the-envelope math, he calculates that the operation would have already sent cocaine with a street value of $2.8 billion to Europe.

“The scale of the seizure shows that they felt very safe storing their drugs there [in the warehouse],” he adds. “This just shows that in Peru the narcos are using every possible means to get their drugs to market, drug mules on commercial flights, down the Amazon river to Brazil, over the Bolivian border, light aircraft from the VRAE, and now this as well.”

![]() Officials in protective gear destroy the country's record cocaine seizure, tossing bags of the more than 7 ton cocaine seizure into a pressurized oven on Sept. 3. Cris Bouroncle/AFP/Getty Images

Officials in protective gear destroy the country's record cocaine seizure, tossing bags of the more than 7 ton cocaine seizure into a pressurized oven on Sept. 3. Cris Bouroncle/AFP/Getty Images

Peru is now the world’s top cocaine producer. There are no official estimates of how much the country actually makes, but experts agree the figure would be in the low hundreds of tons each year.

Most of that, along with Bolivian cocaine, heads to Europe or Asia or is consumed in South America. The US market is supplied overwhelmingly by Colombia.

More from GlobalPost: Why less coca does not equal less cocaine

Mexico is making inroads in this region. Officials have detained dozens of Mexican cartel operatives over the last five years across South America, where they launder money, move drugs, or hide out from law enforcement back home.

This year alone, police have arrested alleged Mexican drug traffickers in Argentina, Ecuador and Brazil, among other countries.

Mexican gangsters first stepped into the cocaine trade in the 1980s, when Colombian cartels hired them to move the white powder over the border into the United States to fuel its booming multibillion-dollar market.

The Colombians turned to the Mexicans after US drug agents backed by the military managed to squeeze the Caribbean route where cocaine was flown or shipped into Miami. The 1,954-mile US southern border proved much harder to police.

However, while the Mexicans began as paid couriers, they gradually ate more and more into the cocaine-trade pie, taking over distribution, sales and transport from the south.

By the early 2000s, the Mexicans were buying up vast quantities of cocaine from producers in Colombia — for some $2,000 per 1-kilogram brick — and owning the rest of the chain.

Now, US drug agents say, their expansion into Peru has been so extensive that the Mexicans even run their own cocaine laboratories here.

Yet Mexican narcos are still far from completely controlling Peru’s cocaine chain. The UN’s Mirella says most labs here are still operated by “local clans” in a decentralized system that limits the damage when law enforcement detects one.

This past week Peruvian newspaper La Republica reported that Brazilian gangsters were also running operations in the VRAE, the Spanish acronym for the Valley of the Apurimac and Ene Rivers, a lawless outpost on the lush slopes of the eastern Andes that now grows more coca than anywhere else on Earth.

More from GlobalPost: How Peru could become America's next drug war debacle

Brazil is the world’s second largest cocaine market, after the US, with cheap crack and cocaine paste popular in the favelas (city slums), while more affluent Brazilians snort the refined powder in increasing quantities.

Citing a confidential police report, the paper named the leader of the gang as Osmar de Souza, a 27-year-old Brazilian with a long record of drug-running that includes escaping from jail in both Argentina and Paraguay. Officers were unavailable for comment to GlobalPost.

But despite Peruvian police setting a new national record for a cocaine seizure, some say law enforcement here still needs to up its game to confront the cartels.

Mirella praised the efforts to track and stop the large amounts of chemicals, such as kerosene and sulfuric acid, that are used to turn coca leaves into cocaine. “Without them [the chemicals], you don’t have a finished product,” he said.

But he believes more could be done to stop money laundering.

“At the end of the day, it is the money laundering that is keeping this business alive.”

That, and the demand for cocaine in cities from Los Angeles to Paris and Tokyo.

Simeon Tegel reported from Lima; Ioan Grillo reported from Mexico City.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!