Kurdish teenager’s ‘honor killing’ fades to memory as Iraq violence swells

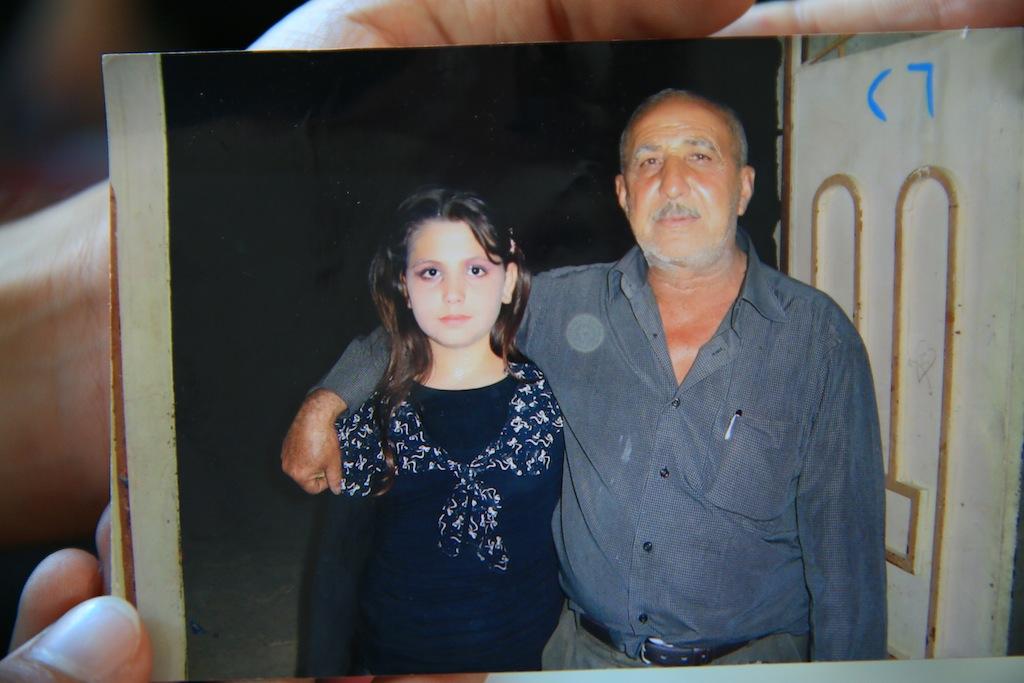

Dunya, aged 12 at the time, stands with her father.

Editor’s note: This story is part of a new GlobalPost Special Report titled "Laws of Men: Legal systems that fail women." This year-long series looks at the breakdown in legal systems created to protect women’s rights around the world.

DOHUK, Iraq — The child’s body was found lying beneath the trees on the outskirts of Shekhan village. Her young, once beautiful face was missing its right eye; her left breast was cut open.

Dunya, just 15 years old, had been shot nine times with an AK-47 assault rifle. Blades of grass were matted in her blonde ponytail. Dunya’s crime? Her 45-year-old husband suspected she was in love with a boy her own age.

“Dunya was very timid. She wasn’t very social and she didn’t care about fashion,” said her mother Sahom Hassan when asked to describe her daughter, found dead on May 24. “On the day she was killed she called me and said, ‘This is the last time you will hear my voice.’”

In many parts of the world, such a brutal and premeditated slaying is not called murder, but “honor killing.” The perpetrators can be husbands, fathers, brothers, uncles or sons. The ‘crime’ can range from sexual relations outside of marriage, to inappropriate dress or having any kind of contact with a man outside the family.

The term “honor killing” stems from the belief that a family’s honor is dependent on the sexual purity of its female members, exempting such crimes from being classified as murder. And in many countries across the Middle East, North Africa and West Asia, the law agrees. While murder is punishable by life imprisonment or execution, there is no minimum charge for honor crimes in some penal codes and the maximum can be as low as six months.

The United Nations estimates around 5,000 such killings are committed each year worldwide, but data is scarce and women’s rights workers believe the real number to be around four times higher.

“In our societies they look at women as just sex and children. We are not equal in law or in society. We are number two,” said Bahar Muzir, coordinator of Zhyan (meaning ‘Life’ in Kurdish) a group that was formed to lobby the government and the public to end honor killing in Iraqi Kurdistan and press for justice for victims like Dunya.

Dunya’s mother sits with her other children in her family home. |

Dunya's case became a household topic in Northern Iraq in the weeks following her murder. But as Iraq stands on the brink of a civil war, cases like Dunya’s have faded into the background. In June, a Sunni extremist group now known as the Islamic State seized control of a large chunk of Iraq stretching from the Kurdish borders in the north to the outskirts of Baghdad. Dunya’s case, once prominent, has become buried in the onslaught of violence, as the semi-autonomous Kurdish region of Iraq vies for independence.

“Everyone is silent now,” Hassan said in regard to her daughter’s death.

On June 8, two weeks after Dunya’s death, her husband released a video message unashamedly confessing to her murder, saying it was necessary to protect his honor and adding that anyone in his position would have done the same.

Lawyers for Dunya’s case told GlobalPost they believe three of Yunis’ brothers and his father were also involved in her brutal murder.

Failures of justice

Dunya’s husband, Sleman Zyab Yunis, 45, already had a wife and nine children. His marriage to Dunya, which took place just after Dunya’s 14th birthday, was the result of a family deal.

Relatives and friends of Dunya said that throughout her nine-month marriage she had endured physical and verbal abuse from Yunis, his wife and his children, most of whom were much older than she was.

Her mother said Dunya had once run away from her husband, but after he implored the family to send her back promising things would be different she returned to her deplorable marriage.

“The underlying issue is a lack of equality,” said Muzir as the Zhyan group convened to discuss Dunya’s case last month. “In our society, a woman is seen as the property of her family and then her husband. They are under the control of the males of the household – to give or sell in marriage, to control their conduct and movements. While progressive families may allow more freedom within the home, society does not tolerate women who make their own choices.”

Laws in the Middle East frequently lay down a separate system of justice for men and women. In cases of murder, exemptions are often issued based on the gender of the perpetrator.

For example, Article 418 of the Moroccan Penal Code states that in cases of adultery, "murder, injury and beating are excusable if they are committed by a husband on his wife as well as the accomplice." Under the same legal system, a wife who kills her husband after catching him with a mistress can face charges of first-degree murder.

In Syria, Article 548 states that “he who catches his wife or one of his ascendants, descendants or sister committing adultery or illegitimate sexual acts with another and he killed or injured one or both of them benefits from an exemption of penalty.”

More from GlobalPost: Seeking justice for victims of rape in Minova, DRC

Contrary to popular belief, the majority of these laws do not stem from Islamic Sharia law but rather date back to the Napoleonic Code, which included an exemption for what is frequently termed in the west as a “crime of passion.”

Influence of Napoleonic laws spread throughout the world via colonization.

“These laws come from the perception — that was only recently overcome in our society — that a woman belongs to her family or to her husband,” said academic and national security scholar of the Middle East and Islamic world Sherifa Zuhur.

Some similar exemptions also derive from the Ottoman Code, which has its base in Sharia law. Although sexual crimes such as adultery are punishable by death, according to Islamic law the perpetrator must be tried, accused by four witnesses and the execution carried out by the state.

While legal exemptions to murder were intended for crimes committed in the heat of the moment — much like a crime of passion — cultural beliefs have led to their usage to absolve families in cases of premeditated honor killing.

In 1990, Saddam Hussein brought this notion directly into the Iraqi penal code by introducing Article 128 that states that murder charges are commutative if committed to “clear the family name or as a response to serious and unjustifiable provocation by the victim."

In 2008, the Kurdish region of Iraq rejected Article 128 along with several other articles used to exonerate men who kill women with Law 14, which states that these articles can no longer be referred to “as a pretext for the clearance of one’s family honor through act of murder.”

For Dunya, this means that her killers should legally face murder charges. But in reality, the new laws have proved difficult to implement.

“Sometimes customs and tribal laws are stronger than national laws,” said Falah Muradkan-Shaker, a lawyer and project coordinator for women’s rights group WADI. ”In this society it is very very difficult. There is not enough awareness, enough knowledge, enough capacity. These traditions have been practiced for hundreds of years and now overnight it becomes a crime.”

Shaker, who also works as a lawyer representing victims of honor crime, said obstacles include a lack of investigation by police, judges who still have a tendency to acquit perpetrators and an unwillingness of witnesses and family members to testify against a perpetrator in honor crimes.

Even with a successful conviction, most are released by pardon decrees within months of their sentencing.

Shaker — who previously spent five years investigating the Iraqi prison system publishing three books on prison conditions and prison reform — said no man has ever served more than a year in Iraq for femicide.

“During my prison research, all the prisoners told me the easiest crime you can commit and get away with is killing a woman,” he said.

While the introduction of these laws is a step in the right direction, Shaker said, due to lack of implementation they are not being taken seriously.

Redefining honor

In Jordan, recent efforts to change laws pertaining to honor crimes have done little to change public attitudes toward the practice. A survey conducted among teenagers in Amman last year revealed almost half of the boys and one fifth of the girls believed honor killing is justified under certain circumstances.

Other nations including Turkey, Egypt, and Lebanon have also either amended laws pertaining to honor crime or established specific laws that criminalize honor killing. However, in all of these countries honor killings continue at an alarming rate. According to Turkey's Human Rights Directorate, there is one honor killing every week in Istanbul and an average of 200 honor killing cases reported throughout Turkey annually, accounting for half of the country’s homicides.

“Honor crimes are increasing not decreasing all over the world. Are they being reported more diligently? We don’t know because no one is cross checking with morgues, or investigating disappearances. But clearly the legislation that is in place is ineffective,” Zuhur said during a Skype interview from Cairo.

As women’s rights have increased worldwide, so have honor killings. Zuhur explained that widening educational opportunities for women globally have increased interaction between the sexes. Social media has provided a further avenue for contact outside the family.

“Families are not able to isolate their daughters in the way they used to,” she said. “This means that women are able to escape the total family control they were subject to years before, but it also means that the families trust them less.”

Greater suspicion has led to accusations and cases of women being killed simply for having a mobile phone or chatting on Facebook. Zuhur referred to an incident in Gaza where a woman was bludgeoned to death by her father because she secretly purchased a cellphone, which he suspected she was using to talk to a man. The official number of honor killings in Palestinian territories more than doubled last year to 27 despite numerous protests and public awareness campaigns on the rights of women.

In some countries, the criminalization of honor killing has simply changed the methods. Zuhur said honor killings are often staged as accidents or suicide. In some families the task is assigned to minors who will likely serve a minimum sentence if convicted.

In Egypt, families usually act in large groups, Zuhur said, citing one case where 10 male relatives killed a woman and her two daughters for alleged relations outside of marriage and threw their bodies into the Nile. These group murders make a case harder to prosecute, she said, while involving the extended family in the murder reduces the chance of anyone testifying against the perpetrators.

In Iraqi Kurdistan, suicide by self-immolation has replaced honor killing in many cases. Most often the decision is made by a woman herself either to escape a life of misery or shame, or due to pressure from her family members. The majority of these are reported as accidents. Dunya’s sister-in-law died three years ago in one such incident.

WADI estimates around 10,000 women have burned to death since the Kurdish region gained autonomy in 1991. Just how many of these were suicides is unknown as such cases are never investigated, Shaker said.

More from GlobalPost: Bureaucracy, corruption and fear thwart justice for trafficked women in Thailand

But changes in law are also slowly beginning to wield their influence in the courtroom.

Last month, WADI’s Shaker served as prosecutor in the trial of Osman Ali Mohammed who killed his wife in front of their children. Decades before, when Mohammed himself was still a child, his own mother had been killed in a slaying orchestrated by her brothers.

On May 20, he was convicted to 15 years imprisonment for the crime, a breakthrough for women’s rights in Kurdistan.

As Mohammed was removed from the court, he turned toward a small gathering of women, among them Bahar Muzir and other members of Zhyan. He spat threats and abhorrent insults at the women vowing he would not serve his time, and would exact revenge against each of them.

His words were a harsh reminder that despite this successful sentencing, women’s rights in the Middle East have a long road ahead, and for the brave women of Zhyan, it is a life-threatening struggle.

“Every time after these cases we receive calls. We don’t know who these people are but we get threatened many many times. They say they will kill us, rape us, everything,” Muzir said.

Within two hours of a recent television interview Muzir gave on women’s rights, she said around 1,000 posts were made on social media of her picture condemning and threatening her. But despite the danger, the women say the work they do is crucial.

“Sometimes it is scary, but we are a big group and I think if we stand together we can protect each other,” said Shanga Rahim Karim, a courageous young member of Zhyan, who continues to lobby for justice in Dunya's case.

“If I am killed, then I will die for an important cause, and I know this group will make a big noise and make awareness for all women on my behalf.”

This story is presented by The GroundTruth Project.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!