The gay sex worker who defied sharia law in Banda Aceh to organize

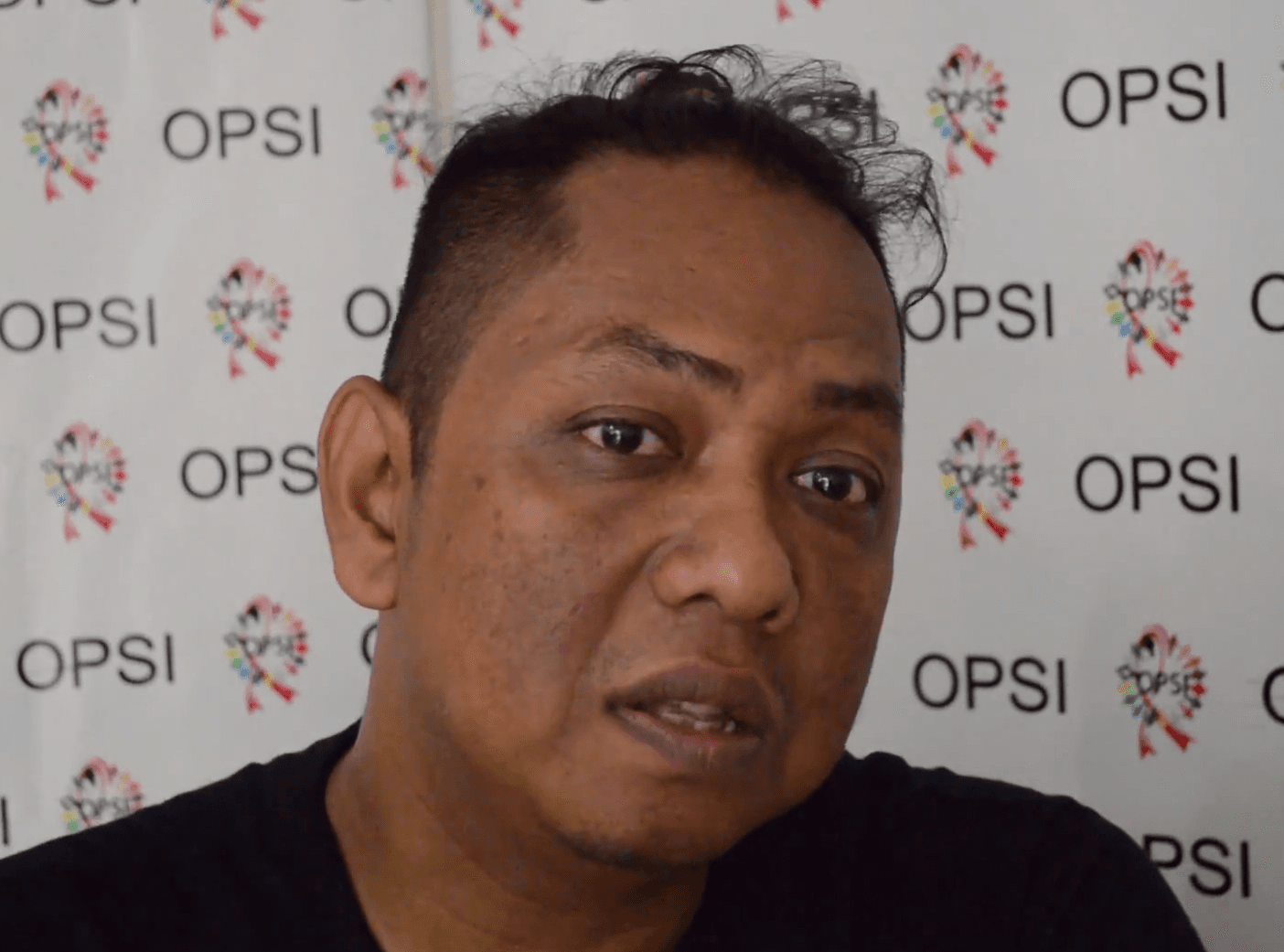

Faisal Riza is a national organizer for the Organisasi Perubahan Sosial Indonesia (the Organization for Social Change, or OPSI) — an Indonesian human rights initiative focusing on the welfare of sex workers.

JAKARTA, Indonesia — Faisal Riza started as a sex worker in one of the riskiest possible places for any kind of transgressive behavior: Aceh, a semiautonomous region of Indonesia that has been governed by sharia law since 2001.

“In my opinion being a sex worker is fun,” Riza said. “When I get a client, I get money. But it’s also difficult to be a sex worker, especially when you get violence from the police.”

Prostitution and homosexual activity are illegal in Aceh, the only one of the country’s 34 provinces in which Muslims and non-Muslims alike are subject to a conservative interpretation of Islamic law.

But Riza and several friends formed a group called Violet Gray to promote sexual and reproductive health as well as HIV prevention in Banda Aceh, the provincial capital. The remote area — on the northern tip of Sumatra, roughly 800 miles from Jakarta — had gotten Internet access just a couple of years earlier.

Riza studied agribusiness in college, but through his work for Violet Gray he began to realize his talent for networking and community organizing.

He quickly expanded his advocacy network and became a local representative for Organisasi Perubahan Sosial Indonesia (the Organization for Social Change, or OPSI) — an Indonesian human rights initiative focusing on the welfare of sex workers.

In 2012 he moved to Jakarta to work for OPSI at the national level.

“My main goal was to increase my capacity as an organizer,” Riza said, adding that the threat of caning for having gay sex also factored into his decision to leave Banda Aceh.

Last year the government of Aceh province passed a law that punishes anyone caught engaging in homosexual behavior with 100 lashes with a cane.

“Now that I’m in Jakarta, I’m not affected by sharia law,” Riza said. “I can freely express myself.”

Transplanting himself from Banda Aceh to Jakarta was clearly a good move for Riza. His demeanor is pixieish, but he looks a bit older than his 37 years. He speaks about the lively community of friends and fellow activists he has made in the capital with the heartfelt appreciation of someone who has had to live a big part of life in the shadows.

Apart from Aceh and a handful of other conservative local jurisdictions, consenting relations between partners of the same sex are legal in Indonesia. But unlike sexual freedoms in most of the Western world, LGBT rights in Indonesia aren’t based on the notion of individual liberty.

Instead, they’re a byproduct of the country’s distinctive constitutional ideals of equality and religious harmony.

Indonesian political culture is religiously pluralistic rather than theocratic or secular. Although belief in God is enshrined in the country’s constitution, there are six officially recognized religions, and the country has nurtured numerous institutions that serve to balance competing religious interests. The most prominent of these groups are Muhammadiyah and Nahdatul Ulama (commonly known as NU), two of the largest Muslim NGOs in the world.

Together they claim roughly 60 million members and provide social services like secondary schools and health clinics throughout the country. They also play important and surprising roles as unofficial advocates for the rights of Indonesian minority groups, including LGBT people.

“In a private capacity, NU and Muhamadiyya are supportive,” said Dede Oetomo, founder of Gaya Nusantara, Indonesia’s oldest gay rights group. “Academics on the left of NU have even written that Islam is not against homosexuality. But they haven’t issued official positive statements about LGBT rights, and the right wing is worried about same-sex marriage.”

According to Oetomo, the influence of the two groups reaches into the highest echelons of Indonesian government.

“A secretary of the cabinet [of Indonesian president Joko Widodo] hails from the NGO world,” Oetomo said. “He’s a secular person, a Muslim, and understands that human rights are universal. But he can’t make a statement on behalf of the president. There’s a lot of don’t ask, don’t tell.”

Oetomo also said that thwarting legislative initiatives to criminalize gay sex at the national level — the last such measure, proposed in 2003, failed decisively — is an aspect of the NGOs’ broader, ongoing opposition to conservatives who want to “Arabize Indonesian Islam.”

“Like with gay people,” he said, “they may not issue a statement that they support Shiites in Indonesia (a religious minority in the Sunni-majority country), but they do.”

That support is often most apparent at the local level, where Indonesia’s relatively weak central government and corrupt judicial system provide opportunities for reactionaries, often enriched by Saudi money, to harass groups that are offensive to orthodox Sunni sensibilities. This harassment includes forcing the closure of mosques that belong to the Shia and Ahmadiyya sects, denying building permits to Christian groups, allowing agitators to disrupt LGBT gatherings and forcing nonbelievers into hiding.

Creating a counterweight against those socially conservative and theocratic forces unites Muhammadiya, NU and surprising array of interest groups, including LGBT rights advocates.

“We still have to be careful because of hardliners,” said Riza of OPSI. “Sometime if we have a meeting or movie screening they try to stop our activities. But our organization has lots of allies. For example, we have a partnership with legal aid organizations that work other LGBT groups and also with atheists and religious minorities.”

One of those organizations is LBH Jakarta (the Jakarta Legal Aid Institute). Rizka Rachmah, an officer in LBH Jakarta’s international program, said that the alliances among unbelievers, religious minorities and LGBT people were not so surprising in the Indonesian context.

“The common cause is they [officials in local and national government] don’t acknowledge these groups,” Rachmah said. “We believe government should not intervene in religious rights, belief or sexual orientation. The government should give protection, but they’re involved in persecution.”

Unlike the United States and Europe, where Muslim minorities, atheists and LGBT rights advocates are often at odds with one another, the shared experience of injustice has forged a uniquely Indonesian set of alliances among those groups.

“Some of the networks of allies made a forum that invited all minority groups to talk about all the discrimination they face,” said Rachmah. “They found many similarities and wanted to work together. There’s a real emotional solidarity with these communities.”

Indonesia’s half-century of dictatorship ended in 1998. While organizations like OPSI and LBH Jakarta have formed since then to speak on behalf of marginalized people, the downside of losing the authoritarian version of Indonesian religious and political harmony is that every faction is now trying harder to make its voice heard above the rest.

“Because of democratization, the bigots have also become louder,” said Dede Oetomo. “In a way that’s the price you have to pay for an emerging democracy.”

Still, as Faisal Riza knows, having allies to protect the freedoms in a democratic society makes it easier to put up with the noisy bigots.

“I am a Muslim, I am gay, I am a sex worker,” said Riza. “Here I can practice Islam and go to every mosque. If I get a partner, I will stop being a sex worker. That’s my goal.”

This story is presented by The GroundTruth Project.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!