Odds against him, here’s how this New York City student made it to college

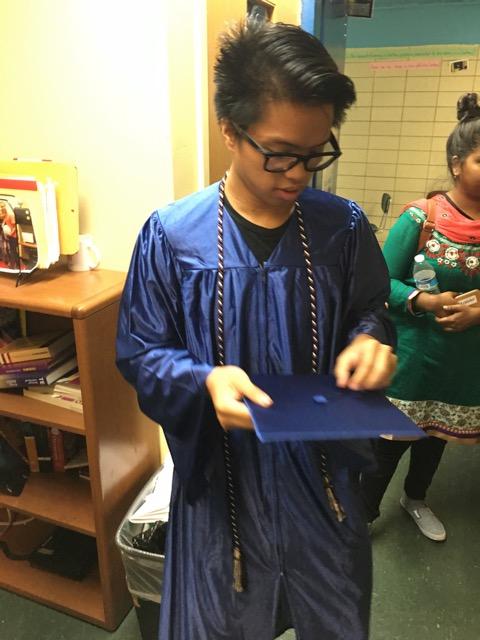

Darwin Cuya was accepted at St. John Fisher College to study nursing. He moved in over the weekend to start summer classes. Five years ago, it didn't seem possible that he would be able to finish high school

Darwin Cuya never thought that he would make it. It didn’t seem possible.

He was wheeling his landlord to a dialysis clinic in lieu of rent and depending on his brother for food, all without his parents around to support him. And he was going to school.

But at ELLIS, the mission is to help students like Cuya graduate. The school’s name is an acronym which stands for English Language Learners and International Support. It was chosen to inspire hope, to be a beacon the way Ellis Island once was for immigrants.

“When I think about it, it’s unbelievable,” says Cuya who, at 20 years old, graduated from high school with a prestigious Regents Diploma in June and was offered a full scholarship to study nursing at St. John Fisher College in Pittsford, New York.

Norma Vega founded ELLIS in 2008 as an alternative high school in the West Bronx to educate newly-arrived, older immigrants, from 16 to 21 years old, who have little or no education and a disadvantaged socio-economic background.

“The vast majority of these students,” says Vega, who is also the principal, “are systematically excluded from even enrolling in regular American high schools.” Their age, lack of language skills and patchy academics makes them unwanted or too hard to place.

Even if they can enroll, the students have often survived traumatic experiences of poverty, violence, displacement or other hardships, which most American public schools do not know how to deal with.

“Those who get in, often leave to go to work or out of frustration,” says Vega.

As a child in the Philippines, he stopped going to school after fourth grade.

“My dad was in the US, and said that it won’t take long for me to come as well,” Cuya explains. But year after year, the papers didn’t arrive. While living with an aunt and waiting to leave, he decided to stay at home.

“[She] could use some help taking care of her children and the store,” he remembers.

He was 13 when he entered fifth grade in New York. He spoke only Tagalog, his native language. He had just moved to the US from Malolos City, in Bulacan, Philippines, and it was the first time his whole family was living together. Back then, he felt like he was living out a cherished fantasy.

“Finally, after all these years, I [could] go with my whole family to a restaurant, watch movies with them, have a picnic in a park or something,” he says.

Unfortunately, the fantasy didn't last.

Cuya is part of a growing influx of immigrant students who are learning English and have had interrupted educations. According to the city’s Department of Education, there were 12,865 students who have had limited or interrupted formal education in New York City’s public schools in the 2013-14 school year (PDF). That’s 9.2 percent of all English-language learners (ELL) above first grade in New York City. The highest concentration of these students are in the Bronx and Brooklyn.

In Cuya's case, his father left him and his mother died. But this isn't only a challenge in New York.

“There’s great awareness now, because they’re arriving in smaller communities that haven’t really dealt with [them] before,” says Julie Sugarman, a policy analyst at the Migration Policy Institute who specializes in education. The arrival of unaccompanied minors from Central America over the last two years has increased the numbers of students who come with interrupted education.

Also: This Kansas high school student must pay back $3,000 after smugglers helped him leave Guatemala

Many of these students start out years behind their peers. At most high schools, they have four years to absorb the language, make up for lost time and earn a diploma. The inevitable outcome is immigrants who are learning English have much lower graduation rates than their American counterparts.

In New York City (PDF), just 34 percent of ELL students (immigrant or not) graduate, compared to 70.5 percent of the overall student population. Nationwide, 62.6 percent of English-language learners graduate, compared to 82.3 percent overall.

“That’s a very big issue,” says Sugarman. “Not everybody in school will understand the context that these kids come from and be sensitive to that.”

At ELLIS, the average high school freshman is 17.5 years old and speaks little to no English. Many are only accustomed to three to four hours per day of schooling, with anywhere from zero to 11 years of prior education upon enrollment, says Jeremy Heyman, ELLIS’s founding science teacher and former college advisor. The school’s 350 pupils come from 24 countries — Albania to Yemen — and English is often not the second, but the third or the fourth language. The majority are male and Latino.

Convinced that knowing the students is essential and that one “cannot remove the socio-emotional aspect of [their] life and expect that they will thrive academically,” Vega and her staff developed a strong counseling structure. “Each student is assigned to an advisor and a counselor to build them emotionally and academically.”

Unlike traditional American schools, there are no separate ELL classes. Instead, ELLIS focuses on both language acquisition and academic content together. It’s a teaching method shared by the Internationals Network for Public Schools, to which the school belongs. Students learn different subjects and demonstrate proficiency by developing projects, giving presentations, going on field trips and completing internships. An extended school year, September through July, helps them learn both in and out of the classroom.

The academy is also the only school in New York that accepts older teens who didn’t yet take New York state’s mandated standardized tests to earn a diploma, or have prior high school credits. Vega established it in the Bronx because the borough had a large share of ELL students in the 16 to 21 age group with high dropout rates. They were being “funneled” into GED programs to take high school equivalency tests, rather than complete their education in classrooms.

But earning students’ trust “so they will tell us when things are going on,” says Heyman, remains perhaps the most important factor.

Cuya was enrolled in ELLIS to stabilize a family situation that unraveled when his father returned to the Philippines without notice, leaving three young sons to care for their sick mother and no one to earn money.

He was the youngest. His middle brother Edward, who is now a senior at Canisius College in Buffalo, New York, was at ELLIS at the time. Their father’s departure almost derailed Edward’s graduation. Darwin Cuya was only 15 then.

“We had an eye out from the beginning,” says science teacher Heyman. At ELLIS, they felt he could use the support and personalized attention of the school’s community.

“It wasn’t easy, but, then, I didn’t have a choice, did I?” Cuya says.

He was visiting his mother — she had leukemia — at the hospital when he realized he had a talent for nursing. “I wanted to help other people like her,” he says. “I wouldn’t want a kid to lose someone so precious.”

But his mother passed away just as he began high school. Soon after, Darwin’s oldest brother Alex, who was supporting the family, lost his construction job. They were on the verge of homelessness and Cuya wanted to drop out.

“I told myself, ‘I’m done, that’s it,’” he says.

But at ELLIS, Cuya was given individualized support to keep up with his academics and the opportunity to talk openly about his difficulties. He studied during breaks from caring for his landlord, and in the evenings, and eventually applied to college.

This level of support would be impossible for regular high schools, which are not designed to respond to such needs. It’s not an easy task at ELLIS either. The school’s graduation rate has been lingering around 44 percent, including this year’s class. Chief among the challenges is the pressure older students have to drop out and go to work full time.

Vega says she is planning to increase support for pupils entering their junior year, when coursework is more challenging. If all goes well, she says, next year’s graduation rate should improve.

Cuya stayed the course when he accepted that his mother was “really gone“ and that he was given a chance she never had. Without ELLIS, he doesn’t think he would have committed to school.

“I really think I wouldn’t be here telling my story,” he says.

Still, it’s one thing to do the work and another to walk the stage on graduation day knowing that the family you always wanted won’t be there.

He got fitted for a cap and gown, but the day he was supposed to walk, Cuya skipped his own graduation ceremony.

Jacqueline Pena, ELLIS’s college counselor and social worker, worked closely with Cuya.

“Darwin expressed to others that he did not go to graduation because his mother was not going to be present,” she says. “Graduation in essence is [another] ending. A time to say goodbye to familiar faces and come to terms with the reality that there is a new journey ahead.”

This weekend, his brother helped Cuya move upstate to start working on his next degree at St. John Fisher College.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!