Police in Rio state killed 78 people in April. Activists worry it’s the sign of a trend.

Brazilian elite police officers take aim near a resident of the Complexo do Alemao slum as they carry out raids to control the escalating violence between drug gangs, in Rio de Janeiro in 2007.

Residents of Rio de Janeiro’s sprawling favelas face a real threat of increased violence by police officers in the run-up to August’s Summer Games, concludes a new report by the Rio branch of Amnesty International.

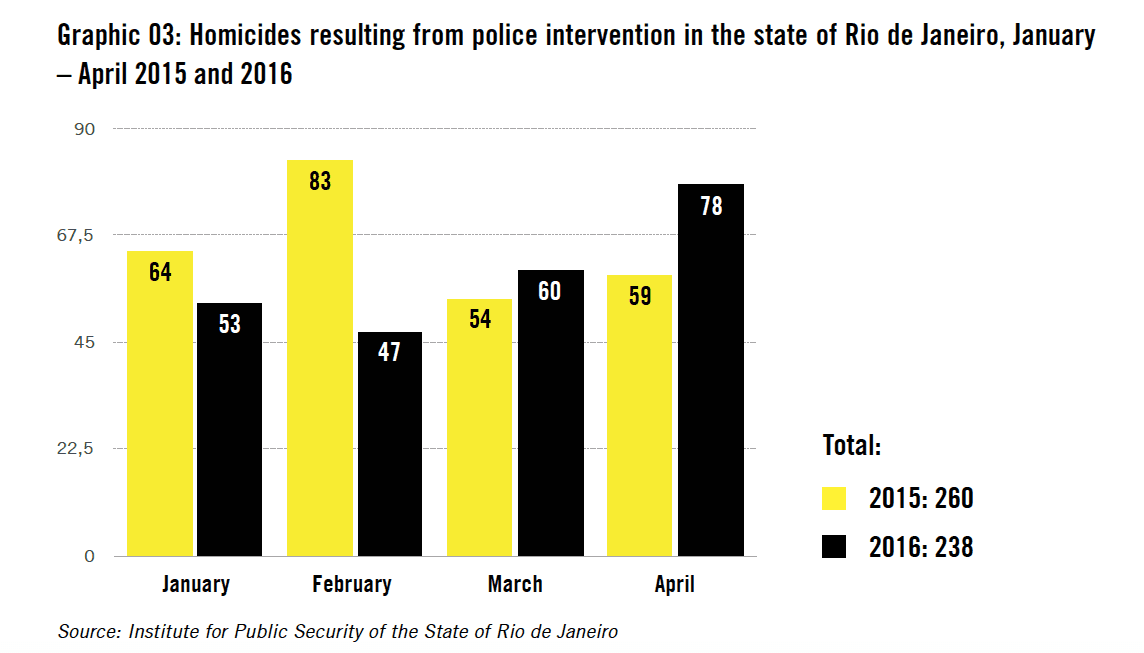

Killings by police officers, long a problem in this crime-plagued city, saw a significant uptick in April. Police killed 78 people that month in the state of Rio de Janeiro, up from 59 killings in April last year, according to the state's public security department. Of those statewide totals, 35 police homicides took place in the city of Rio, up from 20 in the city for the same month in 2015.

“We acknowledge the need to offer a safe environment for those who arrive here to enjoy the Olympics,” said Atila Roque, Amnesty’s executive director in Rio. “But the risk is that increasing security ends up translating to an increase in human rights violations within particular areas of the city, affecting a particular kind of people.”

Previous research has shown that the victims of police killings in Rio are overwhelmingly young, non-white males. Last year, protesters railed against the cops' killings of young black men in favelas.

There was some indication that Rio’s notorious military police planned to crack down on excessive violence when four police officers were arrested and charged with shooting five young boys in November.

Law enforcement officials classify the victims in officer-involved killings as resisting arrest, something that activists have denounced. Often, the killings result from violent clashes between the military police and drug gangs, but favela residents are sometimes caught in the crossfire.

Amnesty says Brazilian officers frequently use "excessive force":

“The Olympic values of friendship, respect and solidarity are not in tandem with the prevailing use of unnecessary and excessive force often employed by security forces, which disproportionately affects young black men in favelas and other marginalized areas.

Brazilian authorities are not only failing to deliver the promised Olympic legacy of a safe place for all, but are also failing to ensure that law enforcement agents, especially the police, meet international law and standards regarding the use of force and firearms.”

Contacted about the violence last month, a spokesperson for Rio’s military police sent a statement defending the agency’s record and pointing out the downward trend in fatal police shootings in early 2016. The spokesperson attributed that to better training for military police officers in the second half of 2015.

“In the first quarter of 2016 there was already a reduction of 24.12 percent compared to the same period in 2015,” they wrote in an email. “The current military police command is aware of these statistics and will continue working to save lives and fight crime.”

The Amnesty report also highlights what it said was the Brazilian government's tendency to suppress free expression ahead of major sporting events. Before the World Cup, for example, the police fought hard against demonstrators who formed massive protests almost daily.

And the report draws attention to the wide-ranging “general Olympics law,” signed by President Dilma Rousseff last month, before she stepped down. It claims the law “imposes new restrictions to the rights to freedom of expression and peaceful assembly in many areas of the host city which might be contrary to international law and standards.”

Roque said the latest Amnesty campaign is essentially a pre-emptive strike to put Rio’s security forces on notice.

“Our campaign is a warning, a call to attention, an invitation to the authorities to pay attention and be aware that more security should not be achieved at the cost of the lives of young people or the cost of human rights being violated,” Roque said.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!