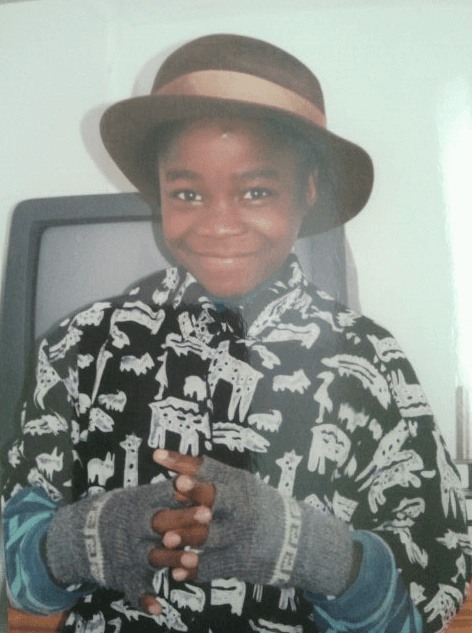

Kids made fun of my ‘stinky’ lunch, which taught me a hard lesson about life in America

When Marcelle Hutchins moved to the US from Cameroon at 8 years old, she loved to eat her mother's peanut sauce. But the kids in her school teased her for her "stinky lunch."

When my family emigrated from Cameroon to the US in 1997, I was 8 years old and many things were new to me. But lunchtime was a whole new universe of discomfort.

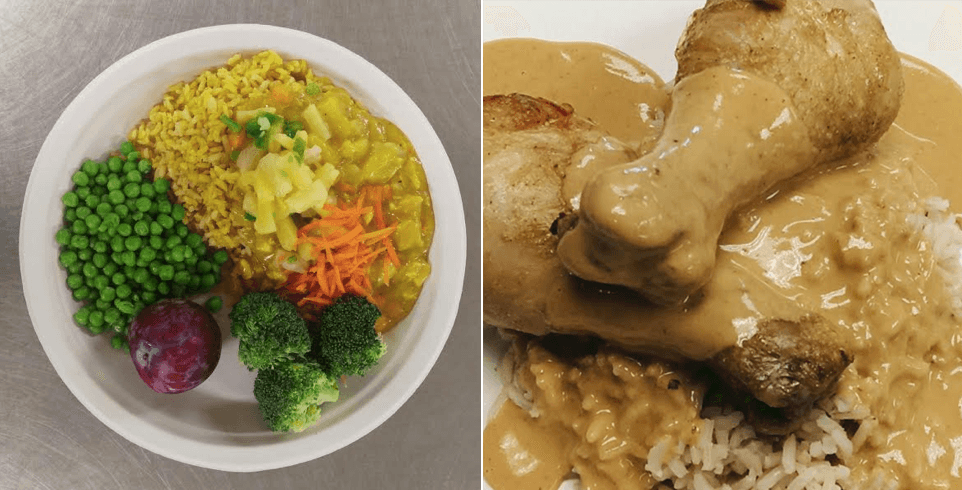

I brought traditional Cameroon food to school — think, peanut sauce with rice — and my classmates would make fun of me and call my meal "stinky." I quickly learned that children weren’t very forgiving about my “strange” food.

Growing up, my family ate a combination of foods, including African and American dishes, and I thought the way we ate was normal. But at my school in Machias, Maine — with a mostly white population of just over 2,000 — my classmates taunted me.

It was a lonely way to grow up. But it turns out, I wasn’t actually alone in my lunchtime struggle.

Ruth Tam, who grew up in Chicago, embraced her family’s Cantonese recipes until a classmate declared her house “Chinese grossness” because of the flavors and strong smell.

“At first I was really angry. I was in high school and old enough to know that what he said was wrong,” Tam recalls. “It was at that moment that I realized that I didn’t want to associate myself with Chinese food.”

Tam, 25, says she was afraid to eat her family’s food in school and began phasing it out of her life. She later wrote about the ordeal for the Washington Post and describes how she came to love her home’s cuisine again.

“It was heartbreaking to think that I was made to feel ashamed of my family’s food. I had this great dad who makes incredible meals, but at the time I didn’t appreciate it because I wasn’t proud of my background,” says Tam. After avoiding Chinese food for a long time, she recently learned to make her father’s ngau lam, Cantonese braised beef brisket.

Things have changed a bit since Tam and I were in school. There are programs to help celebrate different kinds of food now — the kinds of efforts that may have spared me many hungry afternoons.

Minneapolis Public Schools started a program in 2015 to bring culturally appropriate food to 65 sites in the city.

Also: Why a drumstick means progress for some students at this San Diego school

They relied on a guide that provides steps for introducing new foods to students. “Serving Up Tradition: A Guide for School Food in Culturally Diverse Communities” (PDF) was created by Alex Freedman of Foodcorps.

Freedman says that he spoke to immigrants in Lynn elementary schools, just outside Boston; Some students there were concerned that their lunch menus were nothing like what they ate at home.

“I saw that it was exceptionally rare to find schools including food on the menu that reflected the demographics of their student body,” Freedman says.

It’s difficult to determine how many schools serve culturally appropriate food but sample menus for a charter school food service company in the Boston area, for example, don’t have much tailoring to the neighborhoods’ demographics — Freedman says that most schools share their menus online. The guide, Freedman says, has been used mostly around Boston, where I live now. Cambridge Public Schools, Burlington School District and Lewiston Public Schools have all tried some of the recipes in the book.

“I created this guide for food service staff and school food advocates to begin thinking about how to build more foods into their menus that reflected the lived experience of the students eating it,” says Freedman, adding that it’s also about making schools healthier and introducing foods in a way that all students can embrace.

Tam says it’s not just about the food, though. Seeing a range of types of cuisines also helps develop respect for diversity.

“I think it’s a good idea that immigrant foods are being brought into schools,” says Tam. “If there were dumplings and scallion pancakes in my elementary school lunch menu, I would have been more open to sharing my Chinese identity.”

For me, the third grade was very difficult. It took a couple of months after I started school in the US to eat lunch again. I told an English-language teacher that I was being picked on — she offered to eat my mother’s lunch with me in the cafeteria. I decided that I had better just eat the American food if I wanted to have any hope of making friends.

And indeed, the chicken fingers, sloppy joes and pizza opened doors for me with my classmates. The experience taught me a hard lesson: There are times that it’s ok to eat African food, and for your mom to speak French without being embarrassed. And there are times where it’s better not to stand out.

I’m more upset with my school than the children who picked on me. They could have tried harder to make it more comfortable for me — I was isolated in the cafeteria as an African girl at the edge of the lunch room. Still, the experience forced me to get out of my shell and try to adapt to America.

I didn’t fully understand who I was in this new world. As I got older, I started to feel that I should not be ashamed of my family’s traditions. It’s only me who should decide what’s going in my stomach. At 8 years old, I don’t think I could have known better.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!