Soccer's female players may be the key to improving the management of the world's most popular sport, a former US player argues. (Pictured: America's Abby Wambach, walking off the field after her final appearance with the US team in December.)

The world's soccer body just held its presidential elections, but it’s a distant pipe dream that a new president will do much to fix what has bent the "beautiful game" so badly out of shape.

One particular group represents a strong and overlooked potential catalyst for game change: female players.

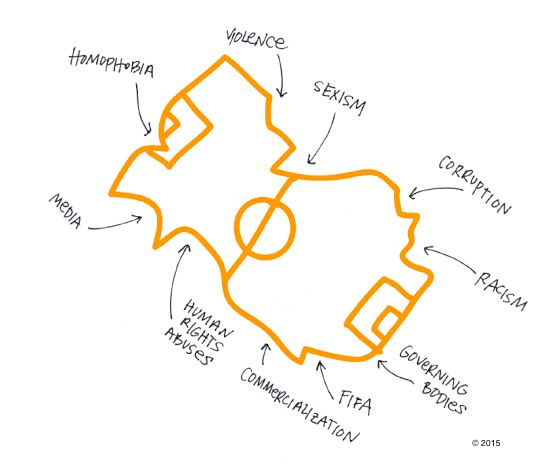

Over the past 18 months, the football industry has been the subject of endless controversy. FIFA’s leading officials have been charged and indicted for corruption. The world’s top female players, forced to play on body-punishing synthetic turf while male counterparts were allowed to stick to natural grass, rightly labeled the move a form of gender discrimination. The World Cup’s elaborate infrastructure has belied the ugly labor exploitation and human rights abuses it has also produced.

Finally, the football transfer system — the buying and selling of professional players — has turned into an unjust employment mechanism that treats people as commodities without protecting their rights. All reveal a system and a game driven by a culture of corruption, discrimination, exploitation, commercialism and greed.

An entire overhaul of the football industry's leadership, governance and structures is required as is a fundamental values shift that prioritizes people over profits. This critical but complicated process will be further challenged by a well-protected status quo.

We cannot wait for (or expect) newly appointed figureheads to lead the change themselves; other game-changers must step up and address those particularly most on the margins.

Certain initiatives are already doing just this from the grassroots all the way up to the global level, where actors like FIFPro, the world players union, that recently launched #GameChangers, are advocating rewriting the rules of the transfer system in promotion of a more sustainable and just model for the game.

Reaching male players at the pyramid’s base who face a constant onslaught of labor rights and human rights violations is essential. These are not the Messis and Ronaldos, but rather the majority of players with employment contracts that do not meet minimum labor law requirements and who confront restricted mobility and limits on access to the labor market. And in this, addressing the realities of female players, even more invisible and marginalized, whose struggle has largely been an undocumented one, is a true litmus test for change.

Female players and those from within the women’s game also provide an untapped source of leadership in the game-changing mission. Women’s football has not been as commercialized and commodified as the men’s. Passion, loyalty and dedication to the game, along with sportsmanship and fair play, flourish because commercial interests are not in large part yet a driving force; and in many parts of the world the women’s game remains nourished by its connection to the grassroots and local communities (who can still afford the match tickets).

And so one could argue therefore that the women’s game has the potential to be a vanguard of change for the entire sport. If it is following in the footsteps of the men, just at an "earlier" stage of development — perhaps representing characteristics of the men’s distant past — could it not, as it grows, leapfrog past the large-scale inadequacies and problems currently confronting men's football, maintaining its purity, and pave a new way for everyone?

Possibly.

But taking this view of the women's game as chronologically "behind" and outside the mainstream of football, is too simplistic and misses the bigger picture.

The women's game may be closer to its local communities and less exploited by commercial interests, but not because it is behind the men's game. Rather, it is a product, outcome and subject of the same football system. It is smaller in size, visibility and value because it has been historically excluded and trivialized by the cultural norms, institutions, and practices of the dominant football industry reserved exclusively to men in most parts of the world.

This exclusion may thus far have shielded the women’s game from hypercommodification, but it has been based on a history discrimination.

And this is precisely where true game-change potential lies. The struggles within the women’s game have cultivated an extraordinarily fertile ground for politicized consciousness and activism. Because their experiences have always been characterized by pervasive gender discrimination, female players can expose and unveil the roots to a dark sideof the game they have known all too well for all too long.

They can raise awareness about the interconnectedness of the underlying circuits of injustice — and bring everyone along by showing how the same processes that have cast women's football to the margins, have thrown the majority of male players into a state of vulnerability and exploitation, and have fed a culture of corruption.

And in this, they can also incite action, politicizing male peers in the process, not around sexism but around a shared goal to end an abusive system that hurts everyone. Ultimately, they can redirect the sport toward a more wholesome, transparent, accountable, respected and admired beautiful game that recognizes its players as people.

This does not prevent the women's game from growing, developing and gaining the broad public support it deserves and enabling women to have the opportunity earn a living as players, which is crucial. But for change to happen, the women's game must refuse equality with the standard of football as we know it. They must demand a new standard — one that stems from equity.

This, however, is too much to request of a marginalized group who, for good reasons, has been striving to gain acceptance in the mainstream. Their fight needs to be acknowledged and all stakeholders must recognize the plight of female players as their own. We must build alliances.

There are concrete first steps. We need to rewrite the rules to the football transfer system. We need more women on the boards of football federations. Transparency is critical. So too are progressive football governance reforms.

World Cups must not be contracted to host countries with records of human rights abuses. Young girls need greater access and opportunities to participate in the game. Local community groups must have greater agency in running their clubs. We need to do these things not because we pity women who do not get a proper field, nor because we feel sorry for exploited male players.

We must do these things because we see this as all one in the same injustice. We recognize that the fight against the corruption and exploitation is also the fight against sexism — captured within sport, but reflective of society.

RELATED: Fighting for equality on the fields of Brazil

Caitlin Davis Fisher grew up in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and captained the Harvard women’s soccer team. She later played soccer at the professional level in Brazil, Sweden and the United States before cofounding the Guerreiras Project in Brazil. She is now a researcher, ethnographer and futebol activist based in Berlin and on the Advisory Board of FIFPro Women.