Why are we seeing so many Westerns on the big screen again?

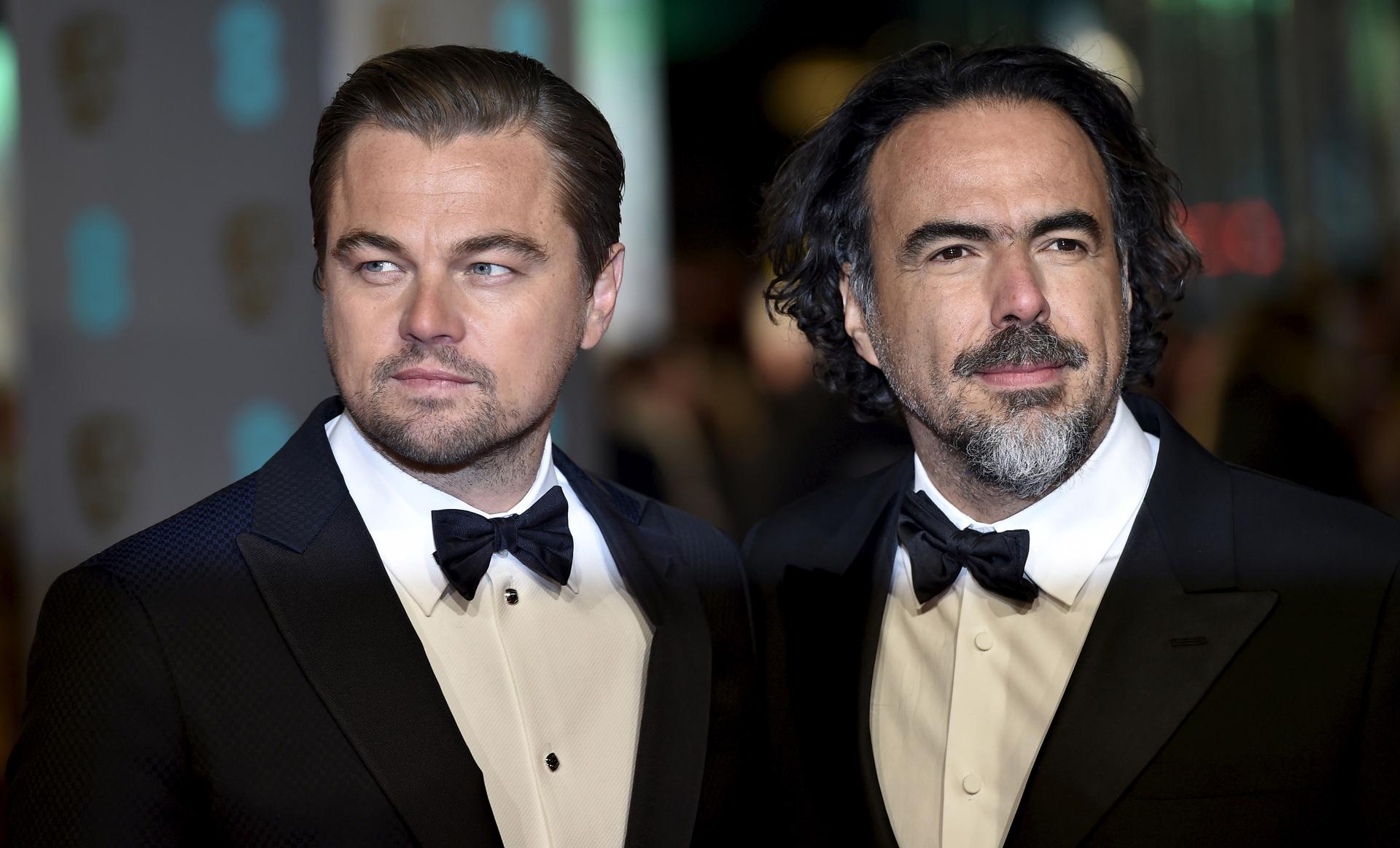

Leonardo DiCaprio and Alejandro González Iñárritu won Oscars for "The Reverant," one of a bumper crop of new American Western movies, breathing life into an old genre.

Western movies are back in a big way. Alexander González Iñárritu's "The Revenant" just won three of the 12 Oscars for which it was nominated. Then there’s Quentin Tarantino’s “Hateful Eight,” and “Jane’s Got a Gun,” starring Natalie Portman.

But Westerns are no longer the John Ford Cinemascope spectaculars of the 1950s or the Italian-made spaghetti Westerns of the ‘60s. Instead, they take elements of those classic Westerns, like core American myths and big cinematic panoramas, and place them everywhere from the 1820s wilderness of “The Revenant,” to the dystopian future of “Mad Max: Fury Road,” to outer space in Ridley Scott’s “The Martian.”

Jeanine Basinger, who teaches film at Wesleyan University, says the thing that really makes a Western a Western is the outdoor scenes, the vast panoramas.

“The thing about the Western,” Basinger says, “Is, if you see this with something like 'The Revenant,' it’s the visuals. It's a way of saying, ‘Don’t stay home and watch this on your wrist watch. Don't look at your iPad. You gotta go out there and let this thing hit you in the eyeball. And you know that's what it did for you as a kid right?”

For Mexican director Iñárritu, “The Revenant” has plenty of outdoor scenes, but still doesn’t fit neatly into the genre. “Sometimes Westerns can be understood by guys with hats, and shooting guns in saloons, getting drunk, you know what I mean?” he says. “And that’s not the kind of Western this is.”

Australian director George Miller also didn’t originally see his “Mad Max” series as a Western. “Until some French critics picked up on the first Mad Max, seeing it as a Western on wheels, it never occurred to me,” Miller says. With outlaws, anarchy and desolate landscapes, Miller says he’s now hyper-aware of his series’ place within the genre.

And while Ridley Scott’s “The Martian” does not feature cowboys and Indians, it does feature a pioneer by himself on the plain. It just so happens, that plain is on Mars.

“[In The Martian it’s] man against the universe, really,” Scott says, “There's no enemies except the planet, the planet was the enemy. So fear will visit once in a while and you have to fight it off…”

Basinger says a wide definition of what makes a Western a Western might not be a bad thing.

“A Western is a lot of different things,” Basinger says, “That's the great magic of genre.”

So why is it that there are so many Westerns and crypto-Westerns at the moment? It may be, Basinger thinks, because core American myths are just as alive as ever: individuality, longing for independence, love of guns and heroic stories, nostalgia for simpler times. Plus, a Western with its remarkable, sweeping landscape demands a big screen, which immerses watchers in images and stories.

“The Western genre as a film genre comes obviously first of all out of the historical fact that we're making movies in America and in America we had the West,” Basinger says, “We had the stories set in the West that were fact and legend and celebrated by dime novels. And we like them because it seemed to be our version of the Knights of the Roundtable or our version of the Samurai.”

This story is based on an interview that aired on PRI's Studio 360 with Kurt Andersen.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!