Leila Al Bakhry at a Women’s Center in Eastern Ghouta.

Leila Albakry, 24, wakes up every morning to the sound of music and a cup of coffee. Her husband joins her, and for a few precious moments they can pretend that life is normal.

But nothing about their life is ordinary.

For starters, they live under siege in eastern Ghouta, a suburb of Damascus, where food and electricity are scarce and potable water is hard to find. The area is controlled by a coalition of rebel groups, including Jaish al-Islam. Residents are subject to constant shelling by the Syrian government and, more recently, Russian warplanes — all the more reason for Leila and her husband to stay focused.

“We try to start our day with a little bit of optimism and hope, and we both go to work. In this way, we try to overcome the sounds of war planes and bombs that remind us that today, new people will die. We might know them and we might not, and we might be among them,” she said.

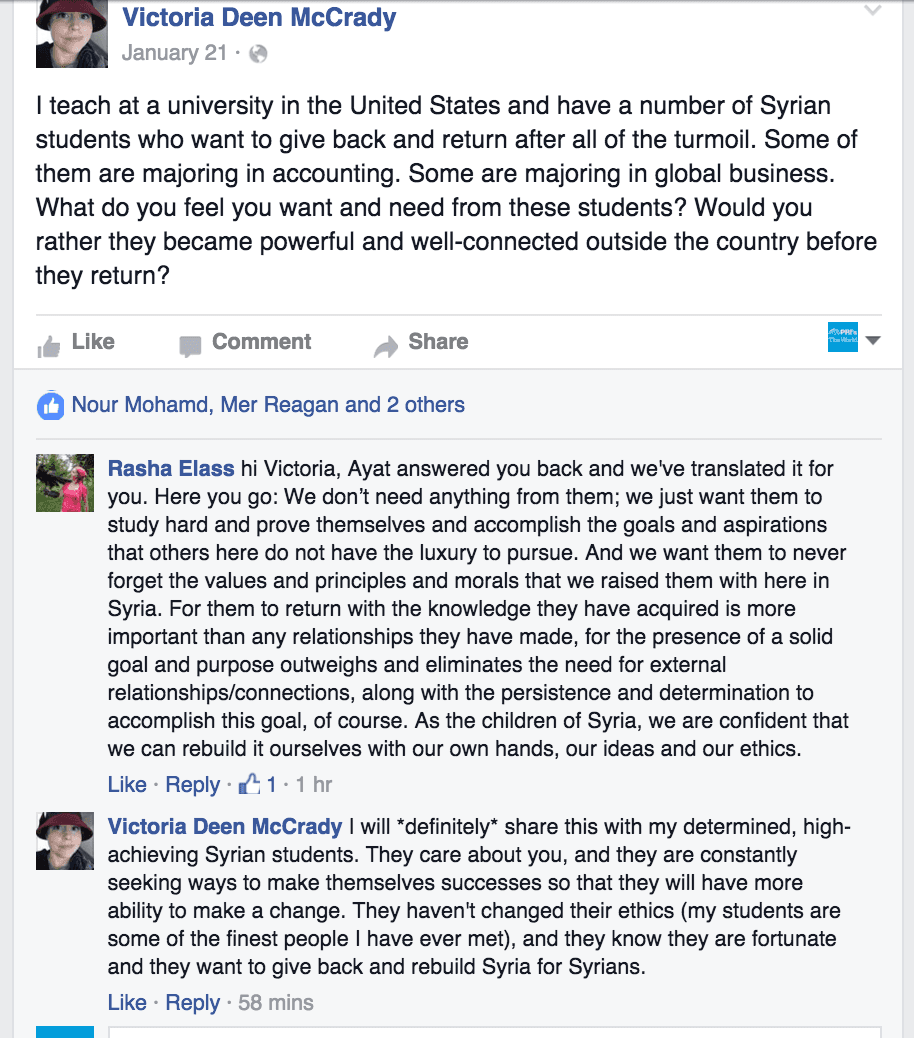

Leila is one of several women in Syria who responded to a series of questions asked in a Facebook chat we hosted to follow up on our story about the changing role of women there. The participants were volunteers with Women Now for Development, a Syrian NGO focused on women’s issues. They value their work as essential for protecting and building their besieged communities, and they leverage their diverse educational and professional backgrounds to train other women in various fields that are necessary for survival in an active war zone.

But for Leila, life has been unexpectedly sweet lately, something she knows she must relish.

“Recently, I gave birth to my daughter Elena, who has filled my life with so much joy,” she says. “I’ve started laughing again, wholeheartedly, at the slightest noise or movement she makes; just looking into her eyes makes me smile and renews my hope.”

It's a far cry from four years ago, when the siege first started and Leila had to stop her studies at Damascus University, where she was pursuing a degree in Agriculture Engineering. She had not yet met her partner, and had not begun working as an educator. She says she plunged into a melancholy state.

“I stayed in my house for five whole months, dying inside from the depression and sadness. But then I began to come out of this depressed state gradually with the help of my family, and particularly my sister, because she made me start working with her in an elementary school that we established together,” she says.

And she knows that hers is no ordinary teacher’s job. The school cannot remain open all day, or even every day, and many classes unfold in the basement of buildings, where it is safest for everyone. Hours of operation depend on the shelling and airstrikes. If the Russian air force is buzzing the skies, parents will not send their kids to school, and teachers can't make it either. If the Syrian government is shelling the downtown area, school shuts down for the day.

“I threw myself into the various types of work that were available and needed to be done. It was through this work that I was able to overcome my depression, because it helped me to see life through a different lens,” she says.

Leila is among the lucky women because her husband is with her to shoulder life’s burdens. But with so many men gone fighting, and so many killed or missing, many women find they must be mothers and fathers all at once.

Another woman who took questions is in charge of a women’s center in Ghouta. She's 24 and asked us not to publish her real name out of concern for her saftey — so we'll call her Ayat. She believes necessity explains how local women have become fierce survivalists, despite a sometimes unappreciative patriarchy that mocks women’s new role in public life.

“…(a) woman has to fulfill almost all of the man’s duties, and this results in huge emotional and psychological burdens dumped on her. So the women here are a force to be reckoned with, in every sense,” she says.

Many men have reacted positively to the gender changes, especially with so many women taking on public leadership roles. But there are men who express their discomfort, even some who have fought these changes with “all their means”, explains Leila.

“But we have reached a point where we couldn’t care less about the opinions of those who want us to just be housewives,” she says.

On a lighter note, asked what favorite Syrian dish she would recommend our listeners try, Leila offered us a recipe that she recalls in detail despite the scarcity of such ingredients in her besieged town.

“You must try tabbouleh, which is a salad made with very finely chopped parsley, tomatoes, cucumbers, and onions. Then you add fine bulgur wheat to it, which had been previously soaked in water for a short time. Season with salt and lemon juice and a sprinkle of dried mint,” she says. “It’s delicious, you should try it!”

To see all of Leila and Ayat's responeses to reader questions, go to the Facebook chat. Here's one of favorite exchanges:

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!