Hundreds of Roman writing tablets reveal early London life

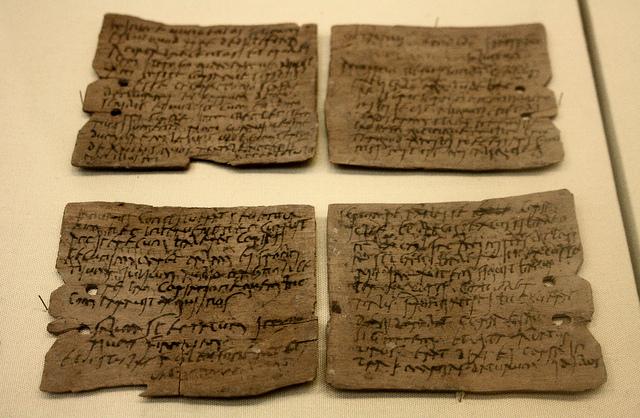

Gallo Roman writing tablet from the Vindolanda Roman fort of Hadrian's Wall, in Northumberland (1st-2nd century AD). Tablet 343: Letter from Octavius to Candidus concerning supplies of wheat, hides and sinews. British Museum in London.

More than 400 Roman writing tablets have been unearthed in the heart of London, shedding light on the commerce-driven life in what would become the City of London financial hub, archaeologists said Wednesday.

The wooden tablets contain the earliest surviving written reference to London, and the earliest dated handwritten document from Britain: January 8, 57 — less than 14 years after the Roman invasion.

The tablets reveal correspondence requesting payments, boasting of money-lending, asking favors to be returned, litigation requiring a judge and also evidence of someone practicing the alphabet.

They also show early London was inhabited by businessmen and soldiers, many from Gaul and the Rhineland.

"It was like the email of the Roman world," said Sophie Jackson, archaeologist and director at Museum of London Archaeology, an independent charitable company which led the dig.

The tablets were found beneath Bloomberg's new European headquarters by the Bank of England.

Romans used waxed writing tablets for note-taking, accounts and legal documents. Writing was carved into the wax, and sometimes the scratches were deep enough to score the wood beneath.

The wooden tablets survived because they were buried in the mud of the Walbrook, a lost river running right through the City of London financial district, still defined by the Roman wall boundary.

The theory is that the tablets were among rubbish which was used to build up the banks of the stream, which now lies deep under the city.

Previously only 19 legible tablets had been found in London. Of the 405 discovered under the new Bloomberg building, 87 have been deciphered.

They reveal the names of nearly 100 people, from a brewer to a judge, soldiers, slaves and freed slaves making their way in business.

The address was written on the back of the tablets.

On one dated to circa 65-80 is written "Londinio Mogontio", or "In London, to Mogontius," a Celtic personal name, and is the earliest reference to London by 50 years.

"The tablets are hugely significant," said Jackson.

"They are the largest single assemblage of wax writing tablets found in Britain and what's particularly special about them is they are so early."

She said they allowed us to hear "the voices of the very first Londoners."