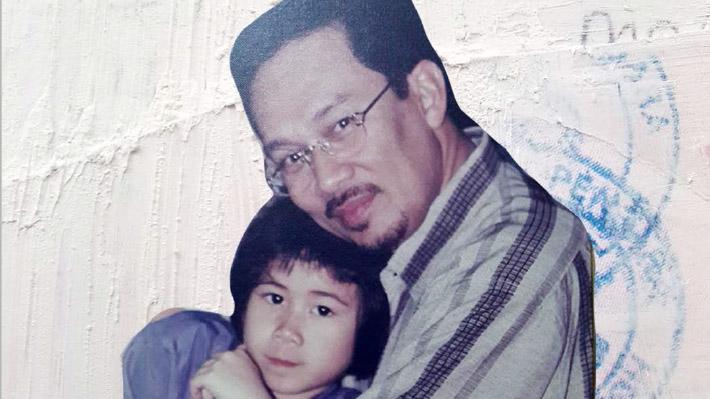

Anwar Ibrahim and daughter Nurul Hana Anwar on the cover of "My Dear Papa."

A little girl is crouched down under a table, her head raised questioningly. Her eyes and mouth look afraid. She asks, “Mom, what is going on?”

It is Sept, 20, 1998. The police have just broken into the house. Her father has been taken. Outside, crowds are milling around, yelling Malaysia’s slogan for reform, “Reformasi!”

Her family tells her that a wicked man — the prime minister — is responsible for whisking her papa to prison. Her mother tells her to pray, to trust in Allah.

The little girl, the youngest of five children, is not told that her father was on the verge of becoming the prime minister, and that now he is the nation’s most famous political prisoner, charged with the crime of sodomy. How does one explain “sodomy” to a 6-year-old child?

The girl’s name is Nurul Hana Anwar. Because Malay custom holds that the child’s last name is the first name of the father, her name essentially reads: Nurul Hana, child of Anwar.

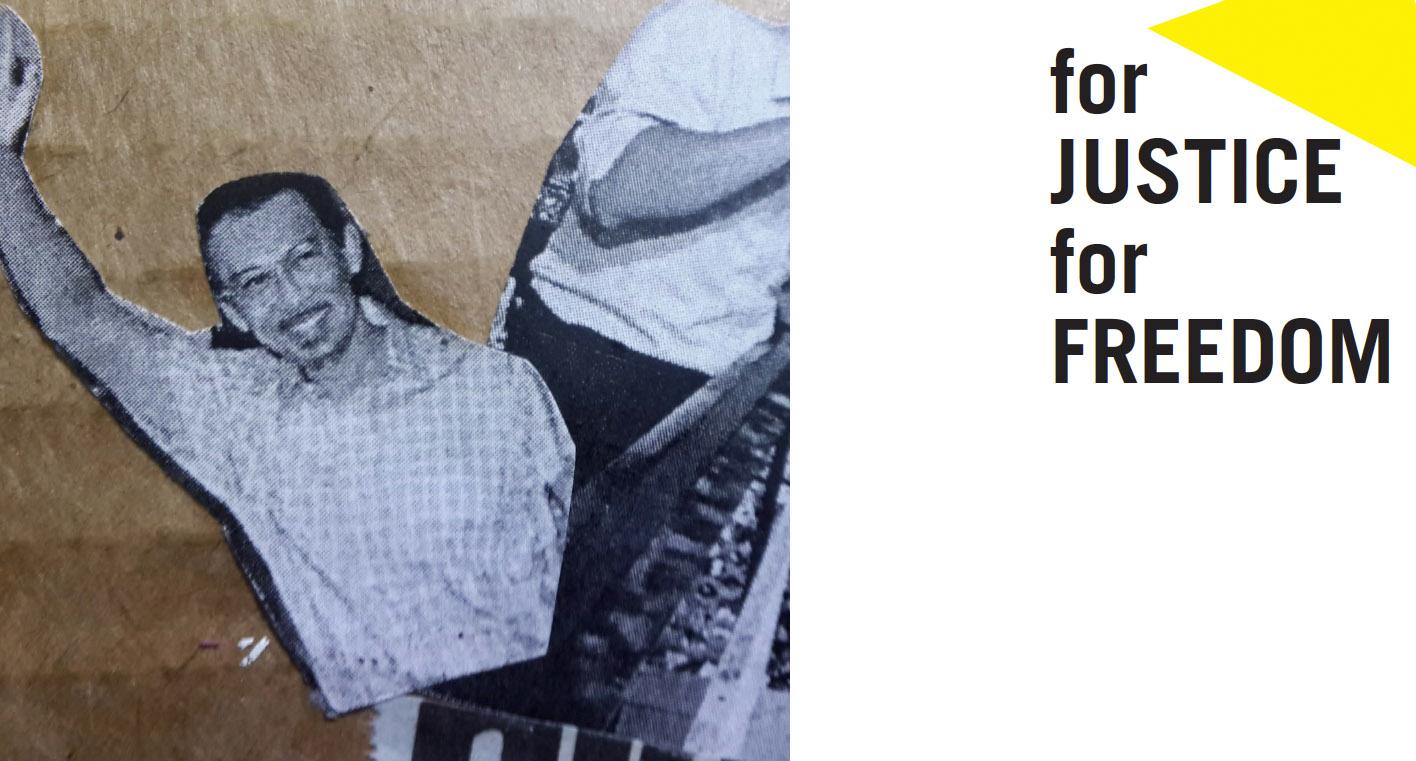

Anwar Ibrahim is a household name in Malaysia. He enjoyed a meteoric rise to power in the 1990s; TIME hailed him on its cover as “the star of a rising generation of leaders” in Asia for his financial reforms and aspirations for democratic reform. He was next in line to succeed his mentor, Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamed, until he had a falling out with Dr. Mahathir over the state’s patronage system. When he was fired on Sept, 2, 1998, Anwar led tens upon thousands of people in political rallies, calling for Dr. Mahathir’s removal and chanting “reformasi!”

Then Dr. Mahathir made his move and had him arrested. For many Malaysians, Anwar’s arrest was the moment of their political awakening; it was the catalyst of Malaysia’s reformasi movement. That night, they realized that if their government could turn on someone as powerful as Anwar, it could turn on anyone.

Nurul Hana did not know about virtually any of this when the men with ski masks and guns broke into her home. For her, it was simply the day that she lost her papa — the day that, according to her mother, she started hiding under tables more frequently, withdrawing into herself and largely ceasing to speak.

Anwar is not a politician in this book. He is a papa, a husband — he is a man. The book has sold well, reaching fifth on Borders' nonfiction bestseller list in Malaysia; it was launched in the United States last month.

Nurul Hana did not plan on becoming an author. The book came out of a collage project that she made for class. We met on a Friday morning during the first week of school in September.

Soft-spoken and friendly, she wears wide, round glasses that sit on top of her full cheeks. We were at a coffee shop, but she doesn’t drink coffee, as she prefers hot chocolate, which she likes to sip as she listens to Radiohead and works on a graphic design project for school.

She had just come back from her book launch in which she spoke to an audience of 150 people, which included many prominent politicians, reporters and leaders. Public speaking terrifies her — she once took acting classes in order to confront her fear — but her talk went well, she said. Still, when she met with a reporter afterward, she asked him to not bring a recorder. She did allow me to record our conversation, but her nervousness was apparent in her frequent apologies and self-conscious smiles. Her body, it seemed, was still getting used to her newfound voice.

The timing of her book is not random. This past February, Anwar was imprisoned for five years yet again on the charge of sodomy, a conviction that the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention has called “politically motivated.”

Many believed he, given his liberal reformist beliefs and devout Muslim faith, was on the verge of uniting the factious Malay Muslims (majority of population), Chinese and Indian ethnicities in order to overturn the dominant coalition. His imprisonment is a significant setback for the political opposition, but some are openly wondering whether they should stop waiting for Anwar and look toward a younger generation of leaders to take the helm.

Nurul Hana’s book does not really care about any of these conversations. It is expressly apolitical, determined to show a different side of Anwar. One of the most repeated images in the book are the photographs of her papa’s feet, covered only by a pair of slippers. When I asked her why she chose his feet, out of all things, to display, she responded by saying most people only know her papa from images or clips of him standing at a podium, giving a speech.

By repeatedly showing his plain feet, which could be mistaken for any other human’s feet, she is revealing Anwar stripped of the trappings of power. When the government imprisoned Anwar, they did not just take away his political career, his job and his reputation. They also took away a grandfather, a father and a husband. In Nurul Hana’s words, “they took everything,” including his body.

If the opposition should move on without their political savior, then the movement to release Anwar will have to rely on less on his political prowess, and more on the basic argument that no human ought to suffer such injustice at the hands of the State. Anwar’s basic humanity will have to be what is at stake — which is why his youngest daughter’s art book might prove more politically relevant, prescient and hopeful than expected.

This is how her story goes.

***

Early in January, her college professor had assigned her class a collage project. Nurul Hana decided to make it about her experience of her papa’s arrest in 1998 and his recent trial. When she tried to create art about her dad during high school in Malaysia, it created a bit of a hubbub. School administrators made her stop; they didn’t want to get into trouble.

Everyone knew who she was back home, but here, in New York, she is just another girl in a hijab. She would turn it in to her professor at the end of the semester, and that would be that.

To start compiling the collage, she opened the folder in her laptop which contained the scanned letters that her papa and her had exchanged while he was in prison. It was a folder that she had left untouched for over a decade. “I started crying and just let it all out,” she said.

The memories started coming back. She started thinking about that night in September 20, 1998. This is how she writes about it in her book:

“I was awakened by noise and commotion, which made me confused but curious. I wanted to know why these unfamiliar sounds came at this late hour of night, when everyone should be asleep. My aunt who took care of me quickly locked the door… I jumped out from bed and quickly unlocked the door. My aunt tried to stop me, but she was too late; I was already outside the room.”

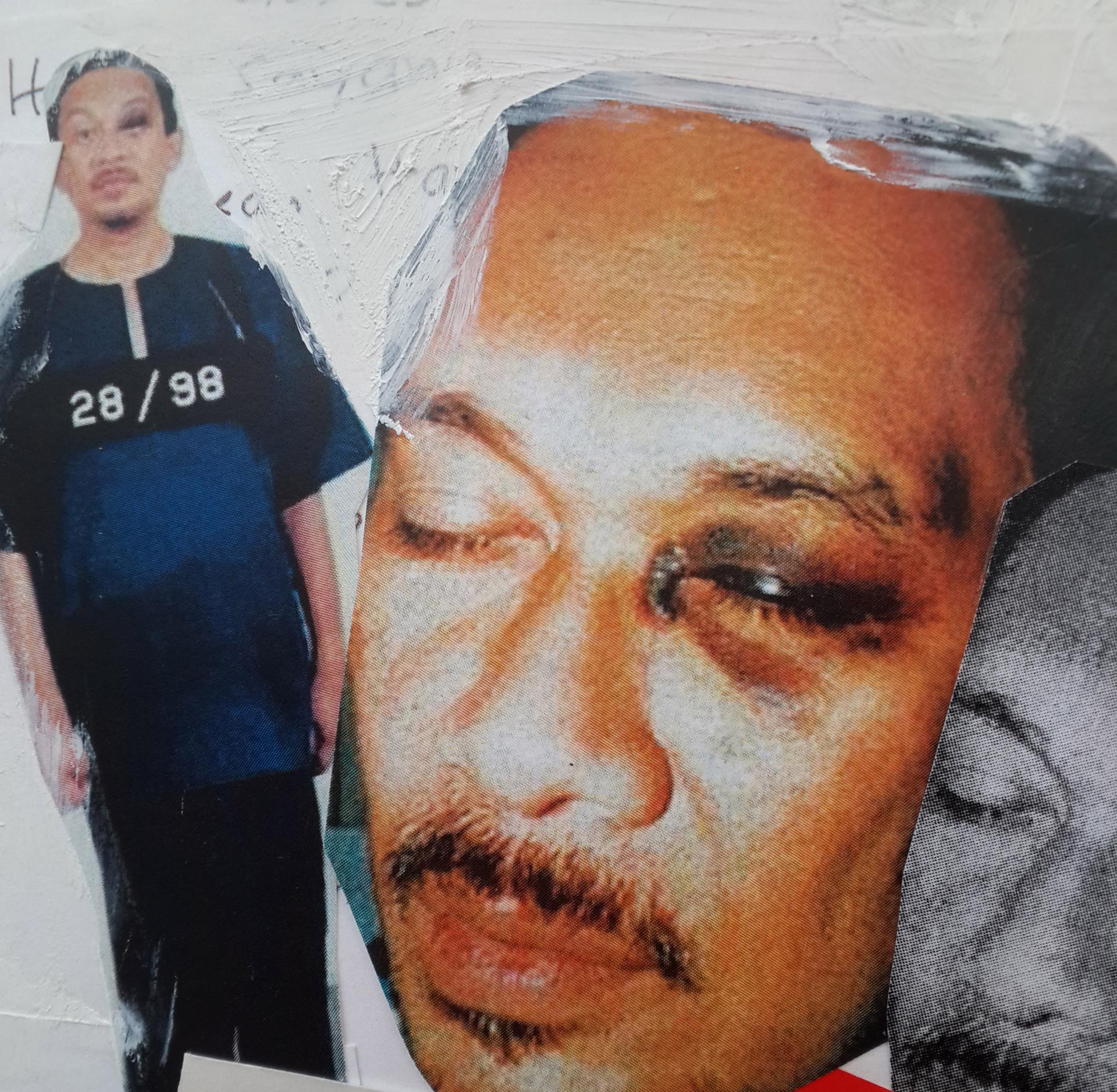

A few masked men in black uniforms were standing outside her parents’ room. The cry “Reformasi!” could be heard from the crowds outside, who had gathered to support her papa. He was given an hour to pack his clothes. They herded him and his family away in a white van; the police had already cleared the streets so no one could stop it. The van stopped. They took her papa out and let him down an isolated road. His family would only know learn of his whereabouts nine days later; they found him in prison with a pool of blood around him. The police chief had beaten him senseless, leaving him unconscious for two days.

For six years, Malaysia’s opposition leader was silenced behind bars. For those six years, Nurul Hana grew up without a papa. They wrote letters to each other while he was in prison. One of the letters is featured in the book: “My cute sweet Hana, you make Papa so happy, so keep up the good work. Take care of your teeth. Finish your homework. Study hard. Smile and don’t slouch! Remember? Love Papa.”

Eventually she became accustomed to the prison visits, and assumed that the way most children saw their papas was in prison. No one told her why her papa was in jail; the word “sodomy” was never mentioned. Whenever someone assured her that “everything would be all right,” she wondered, but never said aloud: “What will be all right?”

The sodomy charge is deliberate in a Muslim majority country, especially since Anwar is a devout Muslim. “He had an image of someone of high moral standing, who’s Islamic in his background. So the best way to destroy that have a charge with sexual connotation in it. And if you can’t get that person to be seen with women, then you might as well deal with sodomy,” Latheefa Koya, a member of his legal team, said.

Newspapers, typically conservative in how they handle sexually explicit material, spared no detail in their coverage of Anwar’s purported homosexual escapades. The law prohibiting sodomy dates back to Malaysia’s time as a British colony; research shows that the law has only been invoked seven times from 1938 to 2009, and that four of the seven times were for Anwar.

The Malaysian Supreme Court eventually overturned the conviction of sodomy, partly due to evidence that the police had tortured confessions out of key witnesses. Anwar was released in 2004. It was only then by reading the news at age 12 that Nurul Hana begin to understand why he was in jail.

“I slowly put the pieces back together,'' she said. "‘What is this?’ I thought. I didn’t tell anyone because I was supposed to know this, and I didn’t tell my mom because I did not want to burden her."

Creating the collage out of newspaper clippings, letters and photos was a way to stitch together bits and pieces of her memories.

“I poured out all of my emotions [into the collage] and it really helped, because I’ve been keeping it in for such a long time,” she said. “I had a normal childhood for six years, but the sad thing is that dad didn’t see me grow up from age 6 to 12, and that’s kind of when you need your dad.”

From 2004 to 2015, the Anwar family enjoyed a respite. Temporarily barred from politics given his criminal conviction, Anwar accepted a position at Georgetown University and took his family to America, where Nurul Hana and her siblings attended American schools. It was the first time in a long time that they could walk around freely on the streets without being noticed. They could breathe a little more easily and lay the past to rest.

They eventually returned to Malaysia. Her older siblings grew up, got jobs, got married, and had kids. Anwar started to gain significant political momentum. In the 2013 elections, he led a coalition of Muslims, Chinese and Indians to win the popular vote.

But his coalition did not gain the majority of parliamentary seats due to electoral gerrymandering. Sources from the ruling party began to hint that current Prime Minister Najib Razak’s future was limited.

The family’s main worry was Anwar’s trial. In 2008, one of his male aides reported to the police that Anwar had sexually assaulted him. Anwar pointed out that his young aide was physically much stronger than him, since his body was, and is, still recovering from the beating in 1998. The charge was later changed to “consensual sex against the order of nature,” but the aide was never charged. The court did acquit Anwar, but the decision was appealed up the ranks. The final trial was set for February of this year.

The trial was on Nurul Hana’s mind as she worked on her collage. She decided she would give it to her papa as a gift when she flew to Malaysia as the family gathered together to hear the final verdict. She kept the project a secret, revealing it only the day before her papa’s court case, when the family was gathered in one room. Everyone was surprised. “It was the first time I talked about how I felt about everything,” she said of her collage. Her mother and her siblings started to tear up.

“You can’t really see [my dad’s] reaction in person, you see it more in his writing — typical dads, you know,” she said, smiling. “He wrote a letter later saying that he was really proud of me.”

The next day, the verdict arrived: the court found that Anwar Ibrahim was guilty of sodomy. He was sentenced to jail for five years.

“I couldn’t really speak,” Nurul Hana said. The silence that came upon her first as a 6-year-old child returned to her at age 23.

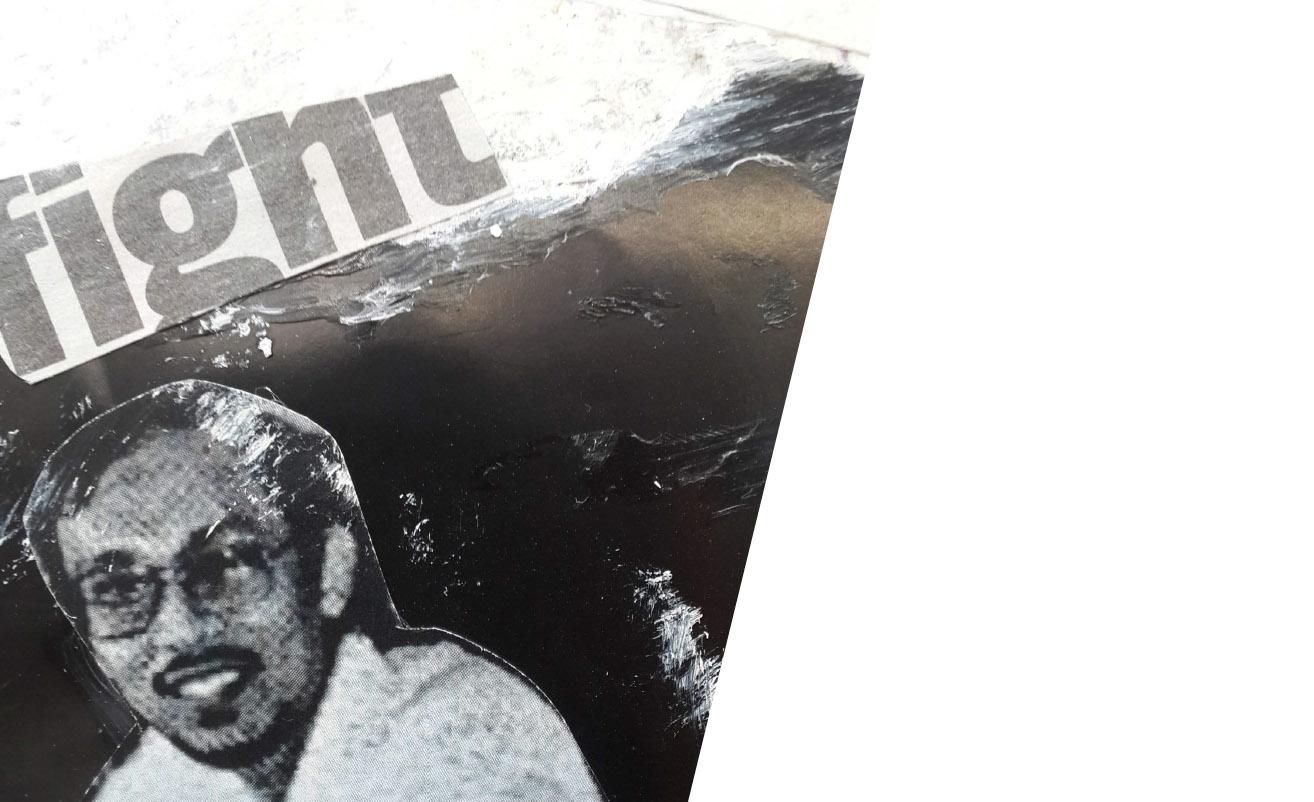

But then Nurul Izzah, her oldest sibling who is also an elected politician, encouraged her to speak and publish the book. At first she shook her head. She explained, “When I finished it, I couldn’t even look at it again.”

The thought of publishing it, to let the world into the most traumatic experience of her life, was too much for her. But after several days – “I’m an indecisive person,” she tells me – she changed her mind. She wanted to tell a different story about Anwar — as papa, not as politician.

“I feel like this book has been silent since 1998. No one has published stories about dad from a family’s point of view … People usually see him as a politician; I just see him as my dad who is wrongfully convicted. People haven’t seen him as a father or a grandfather. They don’t know that he sings lullabies to his grandchildren, or the little things like, when we have dinner or lunch together, everyone has to be there if you are at home. Especially during Ramadan, we always break fast together,” she said.

Because of how closely intertwined the “personal” and the “political” are in Anwar’s career, even a “personal” depiction of him is inevitably a political act. When I asked if she had any particular political agenda in publishing the book, she firmly shook her head, but she did make this comment: “If other families thought the charges were true, they wouldn’t stick to your dad. All our friends and relatives stuck together. If you want to talk about these things, you can still tell it’s untrue because we are sticking together.”

After she returned from the trial to her college in New York City, she said, “It was hard for me to continue my work; I couldn’t really focus. The one thing that pushed me forward was that I want my dad to be part of me by doing good in school, as he has always encouraged me to do, and talking about his message. Those two things I would like to hold onto now that he is not here.”

To be a “good daughter,” for her, inevitably means “to become politically involved.” This is true for the rest of Anwar’s children, who all have been, in one way or another, pushed into the political fray.

When I had met Nurul Hana that Friday morning, she was in the middle of finishing up an assignment about race. Intrigued by America’s racial politics and history, she had just finished reading Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me, a book which she loved.

Her favorite line is, “You cannot forget how much they took from us and how they transfigured our very bodies into sugar, tobacco, cotton, and gold.” The book is a letter from Coates, a black man, to his son, asking him — and the rest of us — never to forget America’s history. Never to forget that propping up the “American dream” are the beaten bodies of black people, bodies that reveal the murderous lie of the dream.

Most of Malaysia’s youth do not really know what happened in 1998. They were too young to understand, just as Nurul Hana was. Her book is directed, in part, to them, to show them a slice of their nation’s history by pulling back the curtain of the State in order to reveal her papa’s bruised and broken body.

The sidelining and silencing of Anwar behind prison bars may be an omen of what is to come. This past year, the government has chosen to revive yet another British colonial law, the Sedition Act, in order to promote a more “stable, peaceful and harmonious state.” Already, 30 politicians and activists have been charged, including a cartoonist, Zunar, who faces up to 43 years in jail for his books and for tweeting a cartoon about Anwar’s conviction.

Last weekend, President Obama visited Malaysia, which hosted the Association of Southeast Asian Nations summit. Nurul Izzah Anwar, a member of Parliament and the oldest sibling in the family, has been campaigning for Obama to hold Malaysia’s government accountable for its human rights abuses.

But Obama needs Prime Minister Najib Razak’s cooperation to wrap up the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement and to fight violent extremism, especially given Malaysia’s geographical location and Muslim population. Islam in Malaysia is becoming much more politicized and radicalized. Struggling to hold onto power, the ruling party has tried to play the religion card by amplifying its Muslim credentials and marginalizing non-Muslims, creating a breeding ground for ISIS recruits — indeed, over 200 Malaysians are believed to have already joined ISIS.

My conversation with Nurul Hana rarely breaches any of these geopolitical topics or concerns. What she is most concerned with is her father’s health — he is in need of major physical therapy and surgery, which the government is not providing, choosing instead to double his dosage of painkillers without telling him. The details that she brings up are personal and particular, such as how the government is stricter than they were in 1998, allowing him to call just one phone number (his wife’s) instead of five. The family gets around the rule by putting her mother’s phone on speaker, so that everyone can dial in and hear him.

Toward the end, we start talking about art and poetry. She tells me about a poem that she read aloud during her book launch, “Gadis Kecil” (A Little Girl), written by Usman Awang, a former National Laureate of Malaysia.

The poem begins comparing a little girl to a firm and thin tree, which stands strong even as other trees fall down in a heavy storm. The girl goes back and forth to meet her father, imprisoned for fighting oppression; barbed wire stands in-between them. The narrator offers her help, but she turns it down, saying, “I don’t need money, uncle, just paper and books.” He offers her sympathy, but she says, “Don’t be sad, uncle, steady your heart.” The girl is young in age, he remarks, but her soul is “matured by experience.” He asks, “Is it not shameful for a grown man / wanting to help suffering prisoners / to receive counsel from the child of one in prison / to be brave and steady?”

Nurul Hana translates the last sentence of the poem for me:

“Ten children like her can vanquish the meaning of a thousand prisons.”