This North Korean defector dreams of being a real estate developer

Elise Park, a North Korean living in Los Angeles, dreams of one day returning home. For now she's studying hard at a local community college.

Elise Park doesn't usually tell people she's from North Korea. She hides in plain sight in LA’s Korean American community, one of the largest populations of Koreans outside of Korea.

Park says Korean Americans make assumptions, they ask too many inappropriate questions about her personal life, for instance how did you come here? How did you get enough money?

“I think, why are you so curious? You don’t ask others, just people from North Korea,” Park says. “I just want to be treated like everyone else.”

Elise Park isn’t her real name. She asked me to use a pseudonym because her brothers still live in North Korea. Park says she left in 2004 because she lost hope for building a life there: Her grandfather had fled to South Korea at the start of the Korean War, and was labeled a traitor. As a result, his family was stigmatized. Park says she was kept from attending good schools or getting a good job.

Like many other defectors, she crossed the Tumen River into China, but she doesn’t want to talk about her experiences there.

“I don’t want to think about that,” she says. “There are things I don’t want to remember.”

Park’s goal in China was to get to South Korea, which she finally did in 2006. She found work as an accountant at a construction firm there, and says that got her interested in real estate development — she liked the analytical side of it. But Park says she was overwhelmed by how much English was part of the business — even in South Korea.

“I couldn’t understand anything, everything was in English. I didn’t know any of it,” she says, laughing.

Park decided to succeed, she had to learn English so she worked three jobs, saved enough money, and got help from Christian pastors to come to the US in 2011. She now attends a community college and says she feels more welcome in the US.

“This is a land of immigrants,” she says. “At work, this person is a Mexican immigrant, that person is an Italian immigrant. That’s comfortable for me.”

Officially, there are fewer than 200 refugees in the US who’ve come from North Korea. But many more come as South Korean citizens after resettling there, so they’re not considered refugees. Referred to as “double defectors,” many of these North Koreans say they left the south because of discrimination. They say they can only get blue-collar jobs, and they’re treated with suspicion everywhere they go.

Park says she still gets that treatment from South Koreans in the US so she protects herself by shielding her past. She says she recently told a Korean American classmate after two years of friendship — it took her that long to decide that “she won’t treat me badly even if she knows where I’m from.”

Young Koo Kim, a Christian pastor who runs a support group in LA called North Koreans in America, says that’s a typical reaction among North Koreans here.

“They don’t trust anyone,” he says. And that makes for a lot of misunderstanding between immigrants from north and south. Kim adds that because of their experience back home, North Koreans here often don’t express gratitude or apologize.

“If they expressed that in North Korea, they were already dead,” he says. “If you do something wrong, you have to grab someone and have them take the blame for them, to survive.”

In her small, one-bedroom apartment in Koreatown, Park has taped pieces of paper filled with English vocab words in her bathroom, on the refrigerator, on the TV. She’s determined to master English.

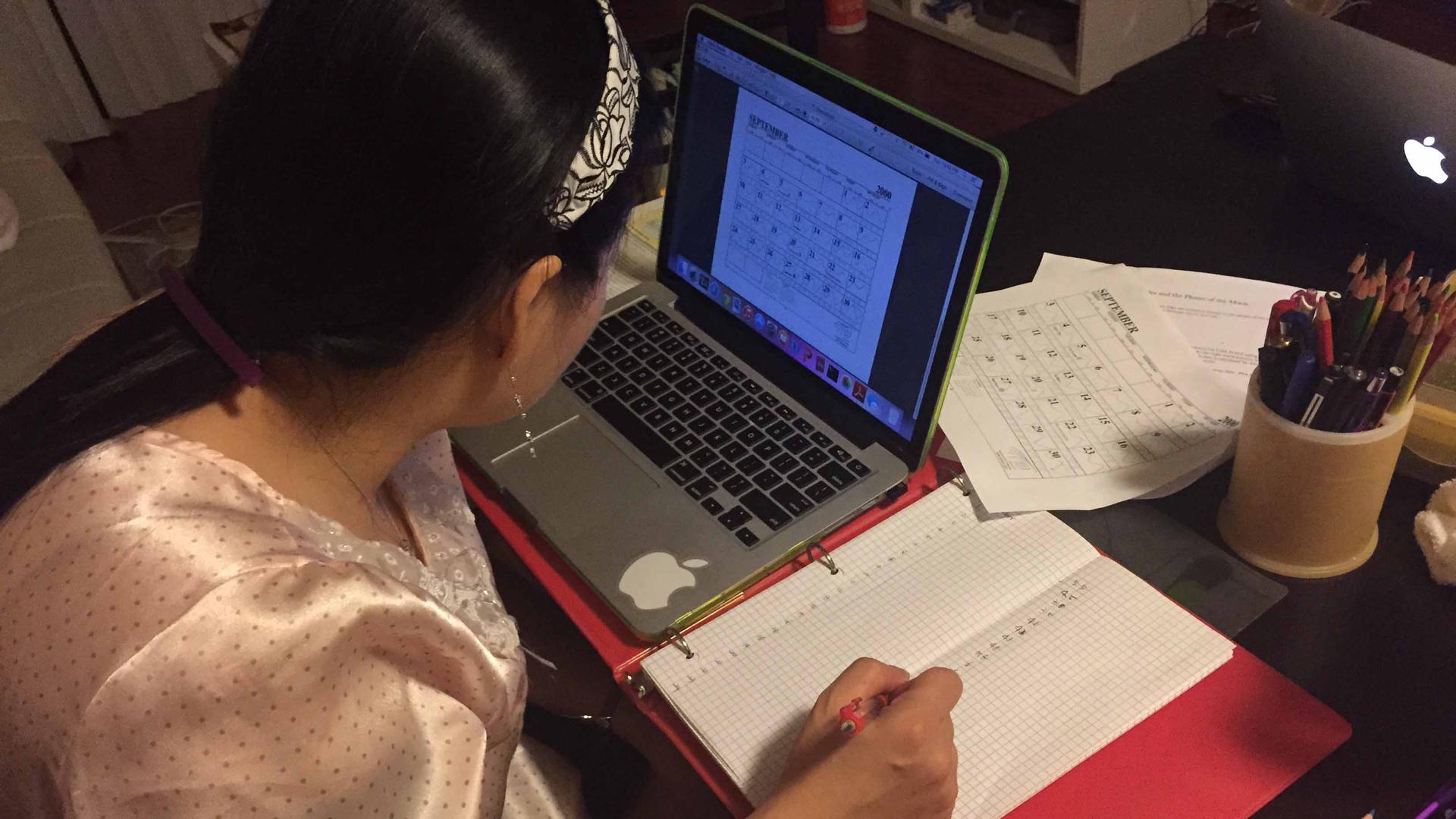

She sits down to do her homework after dinner and stays up until 3 a.m. to complete her oceanography assignment; the technical jargon is tough to understand.

She’s 37 and working hard to get her associate's degree and become an international real estate appraiser. She dreams of going back to North Korea one day to see her brothers. But there’s another reason too.

“There’s no real estate in North Korea,” she says. “They don’t know the concept. I want people there to know how the world works.”

Park says she’s learned how to “take it easy” since coming to the US. But her version of chilling still seems intense. Despite only getting a couple of hours of sleep, Park gets up a few minutes before her alarm starts singing at 5 a.m. to start her week.

Sarah Chee co-reported this story.