As violence rises, some in Venezuela pray to dead criminals for help and protection

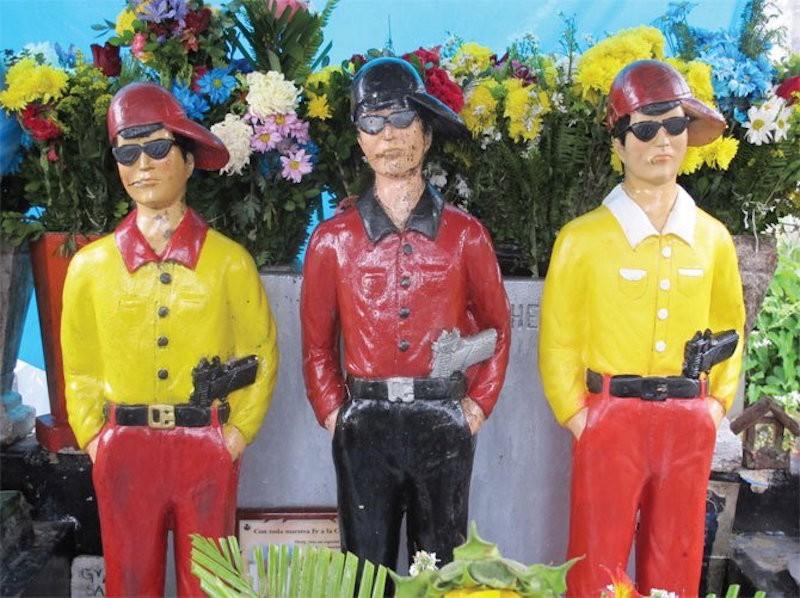

One of the “holy thugs” against one of their graves.

The belief in life after death is common in different societies around the world. As such, funeral rituals constitute the beginning of a special relationship between the living and the dead. In Latin America, this is seen through the belief in the miraculous dead, magical-religious figures revered in several countries throughout the region.

For Francisco Franco, a Venezuelan historian and reference in studies of popular religion in Venezuela, the miraculous dead perform favors and miracles for the living after their death. Generally speaking, these figures were special characters, though no one too outstanding or extraordinary. Mostly, the miraculous dead were once common people:

The Court of Thugs, or Corte Calé, belongs to the cult of goddess María Lionza, one of the popular expressions of the most widespread magical-religious beliefs in Venezuela. These practices are based on the veneration of miraculous spirits and are divided into groups classified under certain hierarchies known as “courts”. María Lionza, along with Felipe the Black Slave and Indian Chief Guaicaipuro, make up the “Three Powers”, the foundation of a heaven of deities that presumably also represent the basis for mixing among white, African, and indigenous people in Venezuela.

The courts can be made up of political, historic, or religious figures. For example, the Court of Liberators is made up of heroes from Venezuela's War of Independence, such as Simón Bolívar, the main leader of this historical movement. The Heavenly Court, meanwhile, is formed by traditional Catholic figures (angels and saints). On the María Lionza Spiritualism blog, readers can find a ranking of the courts and its members.

The Court of Thugs is made up of malandros, a term used in Venezuela to refer to thugs or criminals. These cults are more often seen in urban slums, where violent deaths have increased at an alarming rate since the 1970s and residents see no possibility of protection from authorities. For believers of this cult, the spirit of these criminals can bestow divine favors on them. According to researchers dedicated to this phenomenon, these offenders have certain characteristics in common: in life, they were considered heroes in some way, who robbed for the benefit of their communities.

Followers of this cult visit the graves, build altars in their houses, or attempt to communicate with the spirits through special ceremonies. Some criminals commend themselves to these spirits before committing a crime, or ask them to facilitate access to material goods, such as weapons and motorcycles.

Ways of worship vary, depending on followers and circumstances. Not only criminals turn to them. Mothers, for example, seek to put their children under the protection of these spirits, particularly at night when the journey home through the violent urban slums is riskiest. They also ask them to watch over their children who are awaiting criminal proceedings in prisons. The thinking goes that only those who know the world of violence and bullets are capable of protecting those who live within that environment.

In a documentary from Venezuelan public channel Avila TV, Gonzalo Báez, the president of the Cultural Civil Association of the Followers of Ifá, explains that although the origins of the term calé are not clear, it is thought to be jargon for anyone coming out of prison and is used by inmates to confuse the guards. The documentary also explores the history of the cult's many central characters and explains that part of the mission of these spirits is to prevent others from following the same path that they went down.

oembed://https%3A//www.youtube.com/watch%3Fv%3Dssj2lN75-FI

Though the Court of Thugs predates the World Wide Web, the cult has found a comfortable home online. Tributes to its figures are found on social media, where users give thanks for favors they believe were granted. This video, for example, shared by Enrique Jiménez on YouTube, shows a sequence of photographs illustrating daily life in the neighborhoods and spaces where this cult is practiced. The video brings together many of the symbols of the Court of Thugs: ex-voto (or votive offerings), altars, images of the miraculous dead, and salsa, the music that often accompanies these tributes.

oembed://https%3A//youtu.be/57It9myLSn4

The cult also has a presence on Facebook. For example, thug Ismael Sánchez, the main figure of this court, has a Facebook profile. In it, many followers leave comments and thanks for favors granted and protection received and share photographs of their graves iand the rituals that take place there. Other Facebook pages that are dedicated to María Lionza's cult and spiritualism in Venezuela share stories of these popular idols as well.

In the documentary “Holy Thugs” (published by Vice), sociologist Tulio Hernández explains the role that the miraculous dead cult plays in the lives of followers:

Court of Thugs stories and practices have made their way into the world of Venezuelan film and art, showing just how much the culture of violence has influenced contemporary Venezuela. At the same time, it raises questions about the basic elements of these popular practices. What are the values of a context in which criminals are identified as protectors? Can this be seen as a direct consequence of the state's absence in the everyday life of the masses?

This is an example of how excluded groups seek out protection that is more in line with the world that surrounds them; and many fear this veneration of the criminal could go beyond the religious and influence other aspects of the country, perhaps even the behavior of their elected representatives.

A version of this story was cross-posted at Global Voices, a community of 1,200 bloggers and reporters worldwide.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!