Climate Change & Pacific Northwest Glaciers

CURWOOD: Well, we stick with a watery theme, the frozen water this time of the glaciers of Washington State. The Evergreen State has more glaciers than any other, except Alaska. These ice fields are breathtaking to look at, exciting to climb, and a vital part of the water supply in the Pacific Northwest. But these days theyre melting away. From the public media collaborative EarthFix, Ashley Ahearn has our story.

Jon Riedel, standing just below the Easton Glacier of Mount Baker. He has been monitoring glaciers for the National Park Service for more than 30 years. He’s documented the rate at which glaciers in the North Cascades have been shrinking in recent years. (Photo: Ryan Hasert/ EarthFix)

AHEARN: Guess how many glaciers feed into the Skagit River? Just take a guess. Answer: 376. No joke.

[FOOTSTEPS IN NATURE]

AHEARN: Jon Riedel is hiking up to one of them, on the slope of Mount Baker in Washingtons North Cascades.

RIEDEL: Were headed up along Rocky and Sulfur creeks and then were going to turn and follow Rocky creek up toward the terminus of Easton Glacier.

AHEARN: Riedels been studying glaciers with the National Park Service for more than 30 years. The sheer number of glaciers in this region sets us apart from the rest of the country, but it also makes us uniquely vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Glaciers are key contributors to drinking water supplies, hydropower generation and salmon survival in the Northwest.

Riedel pauses just shy of 4,000 feet elevation in the middle of a field of boulders. No glacier in sight.

RIEDEL: If you were here in 1907 youd be looking right at the terminus of the glacier.

AHEARN (on tape): And now where is it?

RIEDEL: Now its around the corner. You cant see it. The terminus is closer to 4,400 feet and probably at least a kilometer horizontal distance.

AHEARN: Photographs from the 1800s show this whole valley covered in ice. But thats changing. Glaciers in the North Cascades have shrunk by 50 percent since 1900. Riedel says throughout history, glaciers have advanced and retreated over these mountains hundreds of times. But now its different.

RIEDEL: The glaciers now seem to have melted back up to positions they havent been in for 4,000 years or more so weve kind of gone beyond that natural scale of variability.

AHEARN: Glaciers provide billions of gallons of water to rivers in the Northwest. But its not just about the supply – that water arrives when demand is high.

RIEDEL: Having glaciers provides stability to our water supply. So, you get into the mid-late July and the snow is melted out of the mountains, if it werent for glaciers, our stream flow would drop pretty dramatically. So the glaciers are providing this meltwater at a time of year when we get no rain, when the snows gone, in other words, when we need it the most.

[BOAT ENGINE]

AHEARN: Perhaps no one understands that better than the people in charge of operating dams for hydropower.

RAYMOND: My name is Crystal Raymond and we are at the base of Ross Hydroelectric projects.

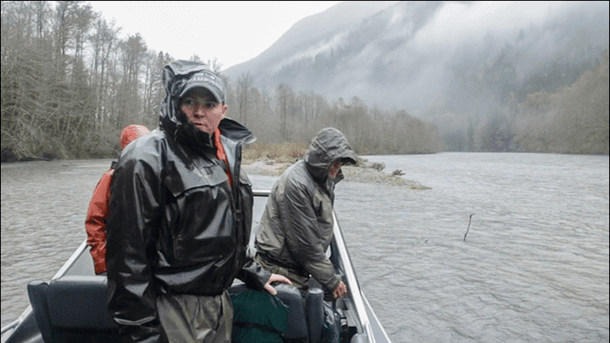

AHEARN: Ross dam towers 450 feet above us as we motor up Diablo Lake in Washingtons North Cascades. Raymond works for Seattle City Light. The utility operates three dams on the Skagit River that provide about a quarter of the power for the city of Seattle.

RAYMOND: So we are unique. There are not too many dams that operate in a place where some of the runoff for the project is coming from glaciers.

AHEARN: At the hottest, driest times of year, glaciers are the biggest source of water for some of the streams that feed this hydropower facility. Its Raymonds job to figure out what to do when the glaciers are gone. She says Seattle City Light will need to change how it stores water above the dams, maybe expanding the reservoirs to capture more rainwater and save it for those late summer months. Helping customers cut back on energy use is also going to be key. By the time millennials are retiring, summer hydropower production in the Northwest is expected to be down by roughly 15 percent. But Raymond is an optimist.

RAYMOND: It isnt hopeless. Theres certainly a lot of uncertainty, but we know enough now to start getting prepared and with time well know more, but the sooner we start the more likely we are to reduce the impacts. And theres no time like the present.

[WATER SPLASHING]

AHEARN: Several miles downriver from Ross Dam, Erin Lowery scans the clear water for salmon nests or redds, as theyre called.

LOWERY: Right there you can see the dark shape, right there in the water. So its sort of near the edge of the redd. So thats a Chinook salmon sitting on the redd.

AHEARN: Lowery is a fish biologist for Seattle City Light. The utility is required to manage its dams to protect spawning fish. Too much water released from the dams and the redds will get washed away. Too little, and theyll be left high and dry. This mama Chinooks tail is ragged and white where shes used it to shovel away the gravelly riverbed to make room to lay her eggs. Now shes guarding them.

LOWERY: Shell sit on that redd and defend it until she loses energy and dies.

AHEARN: And Erin Lowery will do his best to defend her.

[CALLING OUT MEASUREMENTS]

AHEARN: He and his team record the location of the redd and how deep the water is there. Lowery says, glaciers arent just important because of the water they provide in the summer. Its the temperature. Glacial melt flows into warming rivers like dropping an ice cube in a glass of lemonade. No glaciers means warmer rivers, and thats bad news for salmon.

Erin Lowery is a fisheries biologist for Seattle City Light. His job is to figure out where salmon are spawning on the Skagit River and then make sure his employers dams release the right amount of water to allow the eggs to incubate safely. (Photo: Ryan Hasert/ EarthFix)

LOWERY: We start to affect, not only the fish themselves, but it can have a negative effect on their eggs, but in rivers that are dominated or have a glacial component to them, we see reduction in temperature, which is key to cold water fish like salmon.

AHEARN: Lowery says it hasnt come down to a choice between fish or power yet. But he loses sleep thinking about that possibility some day.

LOWERY: I think as we move forward, I mean, its going to be a hard look at how we manage flows in the river with a changing climate, with a reduction in glaciers and snowpack because people are moving to the Puget Sound constantly and theyre all going to need electricity.

AHEARN: Scientists arent sure exactly when the glaciers will disappear. It could be within a few decades. It could be by the end of the century. But when theyre gone, theyll be missed.

Im Ashley Ahearn on the Skagit River.

[MUSIC: Cut Copy Voices In The Quartz from In Ghost Colors (Modular 2007)]

CURWOOD: Ashley reports for the public media collaborative, Earthfix. There are videos of glaciers, salmon and dams at our website, LOE.org.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!