Reporter finds US immigration policies have little effect on migrants coming north

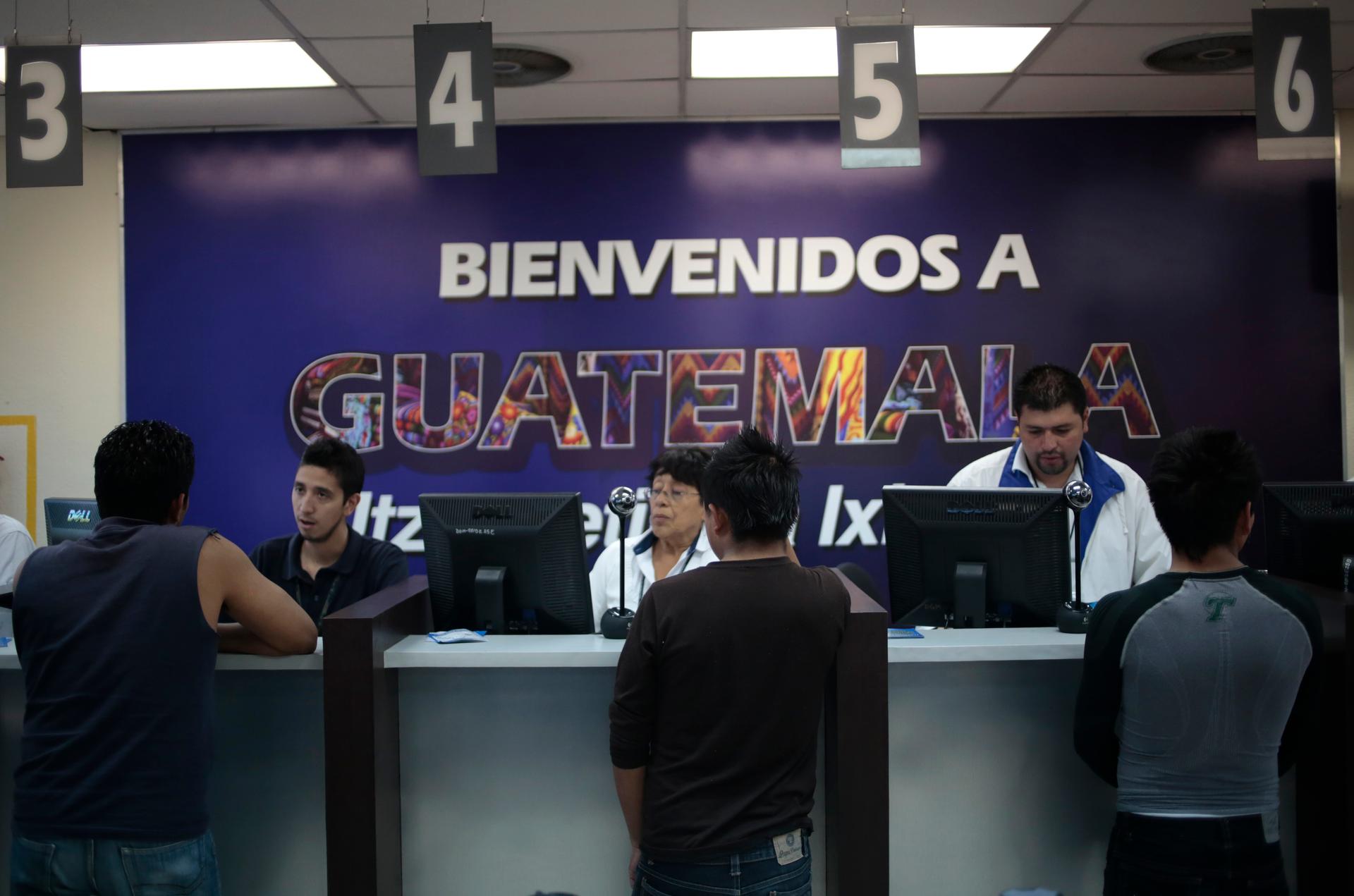

Guatemalan immigrants deported from the US are processed for for re-entry at La Aurora airport in Guatemala City July 15, 2014.

The US Border Patrol has detained more than 52,000 migrant children since last October, a huge increased than the same period in 2013.

As Washington debates the future of the border, reporters at the Arizona Republic decided to go to the source — to the countries these children are leaving behind — to document their journeys to the US.

Reporting from Honduras, Mexico and the United States, Bob Ortega, a senior reporter at the Arizona Republic, discovered that US immigration policies have very little impact on a child's decision to leave their home country.

"The notion that has been put forward by many people, that Obama's immigration policies are somehow enticing children to come north, simply doesn't seem to be true," Ortega says. "It's really clear, first of all, that a significant portion of these children—probably more than 60 percent—are coming north because they're fleeing violence in their home countries."

While in El Salvador, Ortega spoke with two boys who were considering coming to the US. He says that pernicious gang activity in El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala is contributing to the mass migration north.

“One of them had to spend the last four months of high school hiding in his house because the gangs had threatened him,” Ortega says. “The only way he was able to finish high school was his teachers were sending packets home for him to work on. Two of his other friends who were in a similar situation fled — one of them fled to the US and was deported back to El Salvador. He was murdered within a week of his arrival.”

Ortega says he also spoke to a woman who has three daughters aged 19, 16 and 10. Their family had attempted to move north after a gang in San Salvador tried to lay claim to the teenage girls, though they were later stopped and deported from Mexico.

“When I spoke to her, she was desperate," Ortega says. "She of course did not have her job anymore, and did not feel like they could go back to their house because that would not be safe. She said she could not rely on local authorities because they were doing nothing, and had done nothing to protect her or her family.”

When looking back on recent history, Ortega says there are clear connections between extreme violence in places like El Salvador or Guatemala and the US. In addition to gang violence, Ortega also notes the US's historic influence in the instability of these countries.

"When you talk about the roots of violence and the kind of societal violence that you're seeing in these countries right now, that is not something that springs out of the blue," he says. "That is something that springs out of a long, violent history."

The US involvement in El Salvador's and Guatemala's civil wars, along with the American military's use of Honduras as a staging ground in Nicaragua's war against the Contras, has helped contribute to the violence in these countries, Ortega argues.

“When those civil wars ended, the people who were involved in a lot of the human rights abuses, who were involved in a lot of murders, remained in positions of power within the political and security structures there,” Ortega says.

Gangs like Mara Salvatrucha, also called MS-13, and Calle 18 — the two dominant criminal organizations in Central America — both have their origins in the Los Angeles area. Ortega says when the US deported large numbers of people who had criminal records, the governments of El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala were not informed by the United States that these criminals would be returning.

“They were not prepared for them, and they were caught off guard,” he says. “That has continued to be an issue and a very sore point between the governments of those countries and the US.”

This story first aired as an interview on PRI's The Takeaway, where you're invited to become part of the American conversation.

The US Border Patrol has detained more than 52,000 migrant children since last October, a huge increased than the same period in 2013.

As Washington debates the future of the border, reporters at the Arizona Republic decided to go to the source — to the countries these children are leaving behind — to document their journeys to the US.

Reporting from Honduras, Mexico and the United States, Bob Ortega, a senior reporter at the Arizona Republic, discovered that US immigration policies have very little impact on a child's decision to leave their home country.

"The notion that has been put forward by many people, that Obama's immigration policies are somehow enticing children to come north, simply doesn't seem to be true," Ortega says. "It's really clear, first of all, that a significant portion of these children—probably more than 60 percent—are coming north because they're fleeing violence in their home countries."

While in El Salvador, Ortega spoke with two boys who were considering coming to the US. He says that pernicious gang activity in El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala is contributing to the mass migration north.

“One of them had to spend the last four months of high school hiding in his house because the gangs had threatened him,” Ortega says. “The only way he was able to finish high school was his teachers were sending packets home for him to work on. Two of his other friends who were in a similar situation fled — one of them fled to the US and was deported back to El Salvador. He was murdered within a week of his arrival.”

Ortega says he also spoke to a woman who has three daughters aged 19, 16 and 10. Their family had attempted to move north after a gang in San Salvador tried to lay claim to the teenage girls, though they were later stopped and deported from Mexico.

“When I spoke to her, she was desperate," Ortega says. "She of course did not have her job anymore, and did not feel like they could go back to their house because that would not be safe. She said she could not rely on local authorities because they were doing nothing, and had done nothing to protect her or her family.”

When looking back on recent history, Ortega says there are clear connections between extreme violence in places like El Salvador or Guatemala and the US. In addition to gang violence, Ortega also notes the US's historic influence in the instability of these countries.

"When you talk about the roots of violence and the kind of societal violence that you're seeing in these countries right now, that is not something that springs out of the blue," he says. "That is something that springs out of a long, violent history."

The US involvement in El Salvador's and Guatemala's civil wars, along with the American military's use of Honduras as a staging ground in Nicaragua's war against the Contras, has helped contribute to the violence in these countries, Ortega argues.

“When those civil wars ended, the people who were involved in a lot of the human rights abuses, who were involved in a lot of murders, remained in positions of power within the political and security structures there,” Ortega says.

Gangs like Mara Salvatrucha, also called MS-13, and Calle 18 — the two dominant criminal organizations in Central America — both have their origins in the Los Angeles area. Ortega says when the US deported large numbers of people who had criminal records, the governments of El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala were not informed by the United States that these criminals would be returning.

“They were not prepared for them, and they were caught off guard,” he says. “That has continued to be an issue and a very sore point between the governments of those countries and the US.”

This story first aired as an interview on PRI's The Takeaway, where you're invited to become part of the American conversation.