At the World Cup, there are more French-born players playing against France than for it

An Algerian soccer fan waves the Algerian flag in front of the Arc de Triomphe in Paris. With 16 French-born players on the Algerian team, Franco-Algerians have celebrated the Algerian victories with huge celebrations in French cities.

Whether France wins this year's World Cup or not, it has already taken first place in at least one face of the global soccer showdown. France has more of its homegrown players competing for other nations than any other country.

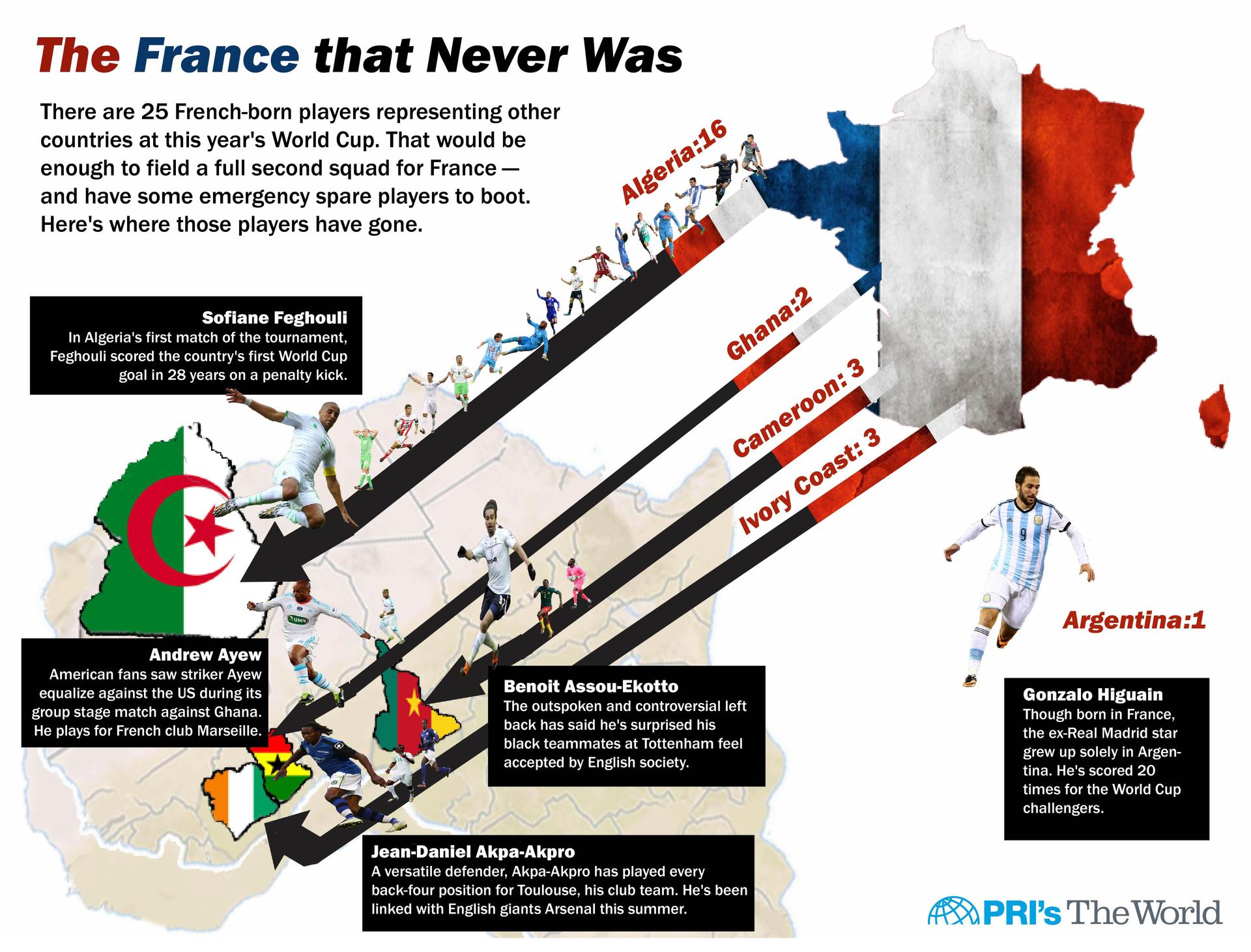

At the 2014 World Cup, there were 25 French-born players representing other countries — 16 alone for Algeria. That's not only enough to field another full team for France, but also five more players than are actually on the French team, Les Bleus, in Brazil.

France's generosity is largely thanks to a rule change by FIFA, soccer's governing body. In 2010, FIFA loosened the rules about player nationality. Now, players who have appeared for a country's youth team, or have only played in exhibition matches, may apply for a one-time switch to another country. "That's a big difference, says Laurent Dubois, a Duke professor and commentator on world soccer. "The generation before had to make up their minds when they were 15 or something."

Before the rule change, debates about race and identity in soccer were largely academic — players could either play or not play for their country, or wait to go through an often-lengthy citizenship process in an adopted country. But since 2010, players have been able to switch their allegiances. And nowhere have players done so more readily than in France. This map shows where they have gone:

France is becoming an ever-more-multiethnic society, sparking sometimes-violent arguments on the role of race and religion in almost every facet of French society. Soccer is no exception. French fans endlessly note and debate over players who do not sing the national anthem. Star striker Karim Benzema, who has scored three times for France at this World Cup, told So Foot magazine in 2011 that, "Basically, if I score, I'm French. And if I don't score or there are problems, I'm Arab."

The French Football Federation even once discussed limiting the number of places for minority players in the country's famous youth training system. Players as young as 12 would have been passed over to make room for more white players.

The proposed quotas sparked an uproar in France, but also led Benoit Assou-Ekotto, who was born in France to Cameroonian parents, to tell the Guardian that "the country does not want us to be part of this new France." Assou-Ekotto chose to play international soccer for Cameroon.

"I have no feeling for the France national team; it just doesn't exist," he said. He contrasted his alienation from French society to the feelings of his black English teammates at Tottenham Hostpur, the Premier League club where he played for years.

"When people ask of my generation in France, 'Where are you from?', they will reply Morocco, Algeria, Cameroon or wherever. But what has amazed me in England is that, when I ask the same question of people like Lennon and Defoe, they'll say, 'I'm English.'"

Assou-Ekotto is known for being particularly outspoken — he was recently sanctioned for his stand on another racially-charged topic, the "quenelle" gesture. Most other players have less to say on issues of identity.

He says his fandom was sparked after France's 1998 World Cup victory starring Zinedine Zidane, the soccer legend born to Algerian parents in Marseilles. "It was interesting to see, symbolically, a Franco-Algerian winning the World Cup. So, for me, it's something important."

Soum thinks nationality is secondary for most minority players in France. He believe they make their decisions mostly because they want to compete in big tournaments, not because of conflicting identities. And, he says, French soccer fans understand those choices.

"Today, football is a market," he concedes. "Imagine, for people like Bentaleb, they are young, 20 years old, and they can play a World Cup."

He means Nabil Bentaleb, the young midfielder who, like many Franco-Algerians, played for France's youth teams. But after an unexpected breakout season at Tottenham, he decided to represent Algeria. Just months after his first Premier League start, he also started all three World Cup games for his adopted country.

And what happens if France and Algeria face off in the World Cup? "It'll be one of these matches where you feel like it's the symbolic showdown between a former colonizer and a former colony. And yet actually, on the pitch, it'll be people who have extremely similar social experiences," says Dubois, the Duke professor.

And it could happen as soon as this week — if both France and Algeria win their games on Monday, they'll meet in the World Cup quarterfinals on July 4.