How to apologize for the Cultural Revolution without blaming the Communist Party

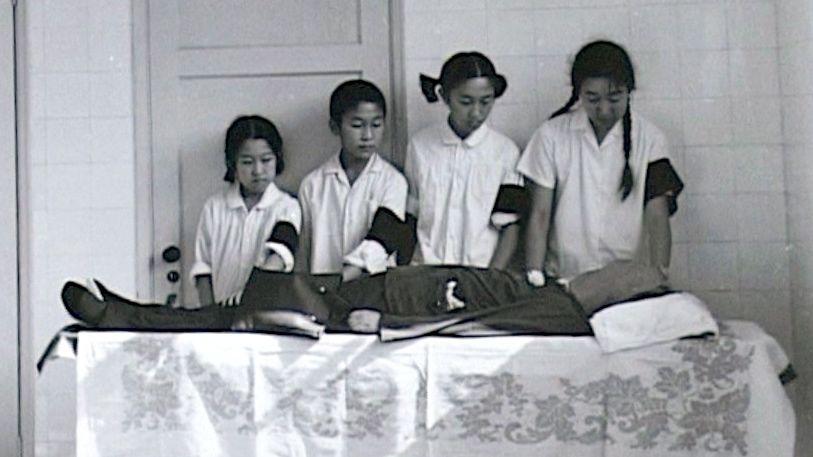

Bian Zhongyun’s children mourn the death of their mother, as seen in the documentary “Though I am Gone.” Bian was a school principal who beaten to death 1968 by a crowd.

It's been 25 years since Chinese forces opened fire on students encamped in Tiananmen Square. But that's recent history.

Too recent for anyone to start apologizing for their conduct. Not so the Cultural Revolution.

The Cultural Revolution is far enough in the past (1966-76) for people to now start taking blame for some of its bloodiest moments. Of course, many of them are reaching the end of their lives, and may feel the need to atone for their actions.

The words of these confessors are carefully, sometimes artfully chosen. With few exceptions, they go out of their way not to blame the Communist officials for inciting them — though government rhetoric at the time set peasants against landowners, the uneducated against intellectuals.

The words of these confessors are carefully, sometimes artfully chosen. With few exceptions, they go out of their way not to blame the Communist officials for inciting them — though government rhetoric at the time set peasants against landowners, the uneducated against intellectuals.

In the podcast, I ask The World's Matthew Bell about this. He recently reported two stories out of China, also included in the podcast, which deals with different aspects of how the Cultural Revolution is remembered.

In one, Matthew visits a Cultural Revolution-themed restaurant, and speaks with a well-connected business executive the who has publicly apogized for his role in beatings of staff at a middle school.

It was a significant apology: Chen had been a local leader of the Red Guards, the stormtroopers of the Cultural Revolution, and he is the son of a Chinese army general who was close to Mao Zedong.

In Matthew's other story, a Chinese filmmaker tells the story of a Beijing high school principal killed by mob of schoolgirls armed with homemade spiked clubs. The schoolgirls had been radicalized by Red Guards.

The story you just read is available to read for free because thousands of listeners and readers like you generously support our nonprofit newsroom. Every day, the reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you: We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

When you make a gift of $10 or more a month, we’ll invite you to a virtual behind-the-scenes tour of our newsroom to thank you for being with The World.