Viral Video “Kony 2012” sparks activism, criticism

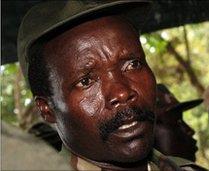

Joseph Kony, the leader of the Lord’s Resistance Army in Northern Uganda, is now the subject of a controversial video that has gone viral over YouTube. (Photo courtesy of Wikimedia).

Out of relative obscurity, the name Joseph Kony has achieved fame across international social media networks this week.

The video “Kony 2012” tells the story of Joseph Kony, who was indicted for war crimes by the International criminal court back in 2005 but remains at large. Kony and his Lord’s Resistance Army (the LRA) are accused of abducting and training child soldiers to kill thousands of people in Northern Uganda.

The caption posted under the “Kony 2012” video reads, “KONY 2012 is a film and campaign by Invisible Children that aims to make Joseph Kony famous, not to celebrate him, but to raise support for his arrest and set a precedent for international justice.”

According to social media statistics, their campaign is succeeding. The hashtags #stopkony and #Uganda have both trended globally on Twitter. Celebrities including Oprah, Rihanna and P Diddy have publicly joined the campaign. And the YouTube page for “Kony 2012” has received over 55 million views and 400,000 comments as of Friday morning.

However, not all the response to the video has been positive. The sudden surge of attention on the Kony 2012 campaign has brought criticism against the management of Invisible Children.

Fulbright scholar and journalist Michael Wilkerson, believes the video’s portrayal of events in Uganda is misleading.

“I think this campaign is incredibly glossy in a bad way, a little bit too shallow, and it’s potentially misguiding a lot of people in a way that may have negative consequences in the long run.”

Wilkerson said that the video portrays Northern Uganda as the location of the rebel activity even though the region has been peaceful for years.

“Awareness is great, but if you ask your kids, ‘what do you think this video means?’ and they say, ‘we need to go to Northern Uganda,’ which is the reaction I’ve seen thousands of times in the last 24 hours, that’s factually incorrect,” Wilkerson said. “Northern Uganda has been peaceful for six years. Kony and the remainder of the LRA were driven out by the Ugandan military.”

Wilkerson also criticized how Invisible Children uses its funding.

“They spend 2/3 of their budget on advocacy and awareness raising in the United States,” Wilkerson said. “A lot of that is film production, a lot of it is road shows where they take their 12 videos now on tours around the United States. They also have some traditional NGO-style education and other programs on the ground in Uganda, but it seems like they’re trying to do a little bit of everything and are not necessarily great at anything except making the film and viral marketing.”

Wilkerson is not alone in this critique. Many online commentators believe that Invisible Children could use their funds more effectively.

In a blog post written for the British newspaper The Independent, Musa Okwonga, an author of Ugandan descent, argued Invisible Children’s video promotes “top-down” activism while failing to mention local forces that are working for change.

“Invisible Children asked viewers to seek the engagement of American policymakers and celebrities, but – and this is a major red flag – it didn’t introduce them to the many Northern Ugandans already doing fantastic work both in their local communities and in the diaspora,” Okwonga wrote. “It didn’t ask its viewers to seek diplomatic pressure on President (Yoweri) Museveni’s administration.”