Immigrant communities connect with Indigenous products to nurture, heal during pandemic

Editor’s note: This article was produced as a project for the Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism, a program of the USC AnnenbergCenter for Health Journalism’s 2020 National Fellowship.

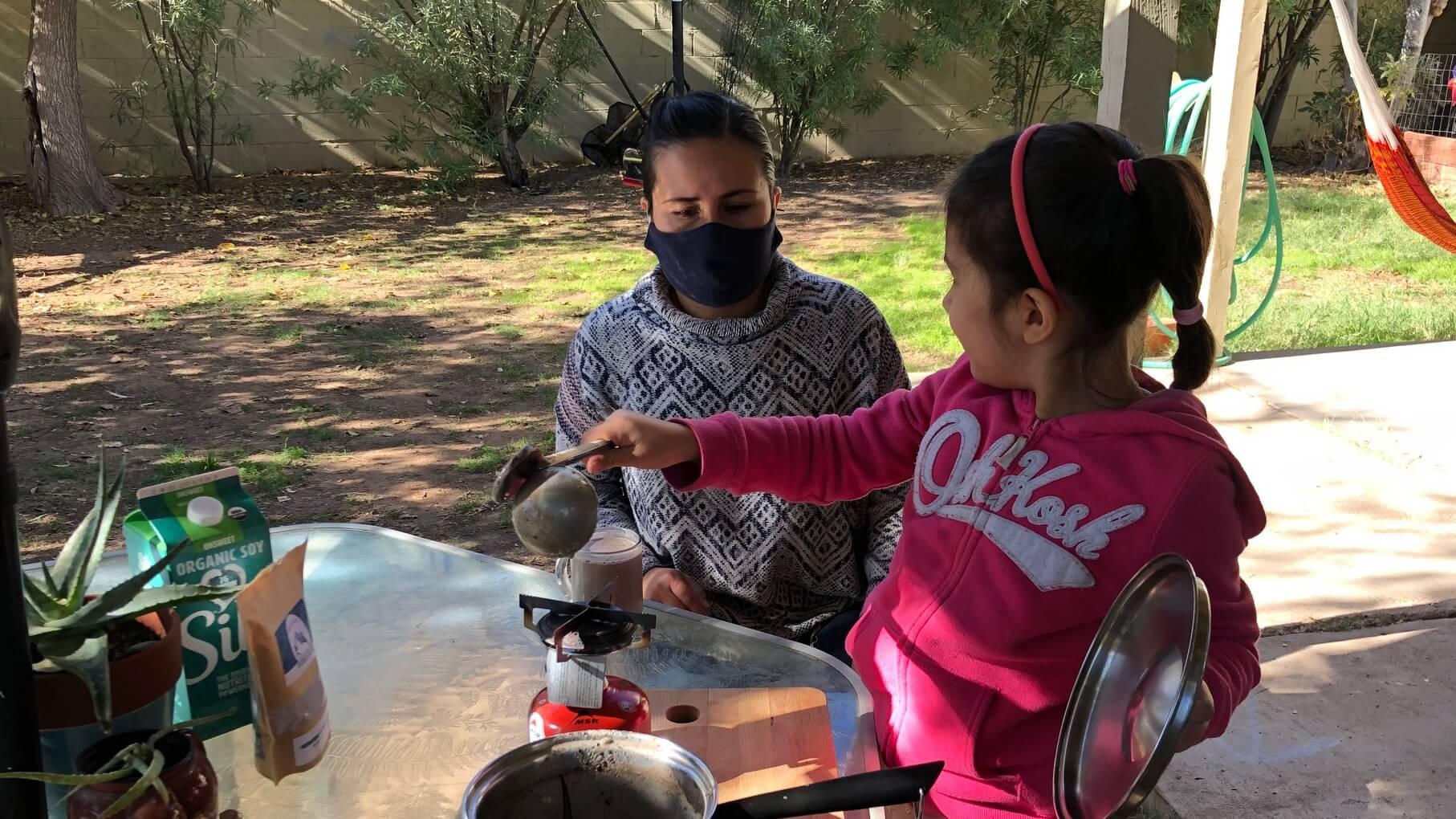

During 6-year-old Catalina’s lunch break from online school, she watches her mother, Sharah Nieto, as she prepares one of her favorite drinks on their patio. Nieto is making atole, a traditional Mexican drink using pinole (ground corn), almond milk and a bit of chocolate, served hot. Sharah Nieto grew up in California, but the smell of atole reminds her of her mom. Her parents are from Yucatan and Chihuahua, Mexico.

“Something like pinole, for instance, is a part of who we are and has been a part of our ancestral heritage for a really long time. … I have an opportunity to share that with my daughter and hopefully someday she’ll share that with her kids, too.”

“Something like pinole, for instance, is a part of who we are and has been a part of our ancestral heritage for a really long time,” Nieto said. “I have an opportunity to share that with my daughter and hopefully someday she’ll share that with her kids, too.”

Related: A therapists’ network supports immigrants, advocates during pandemic

In March, Nieto was furloughed from her job as an arts educator, but she and her partner are artists so they’ve been making extra income through other projects. Money’s been tight, so moments like this really nourish her.

Nieto got the pinole and a big bag of other Indigenous products for free at the Cihuapactli Collective, a group based in Phoenix that started five years ago to offer postpartum support to women. With the pandemic, it was clear they had to do more.

Related: Mexican American family shows how identity, politics diverge

Providing food care packages was a natural extension of their community work because nutrition has always been a big part of supporting women, said chef Maria Parra Cano, one of the founders of the Cihuapactli Collective.

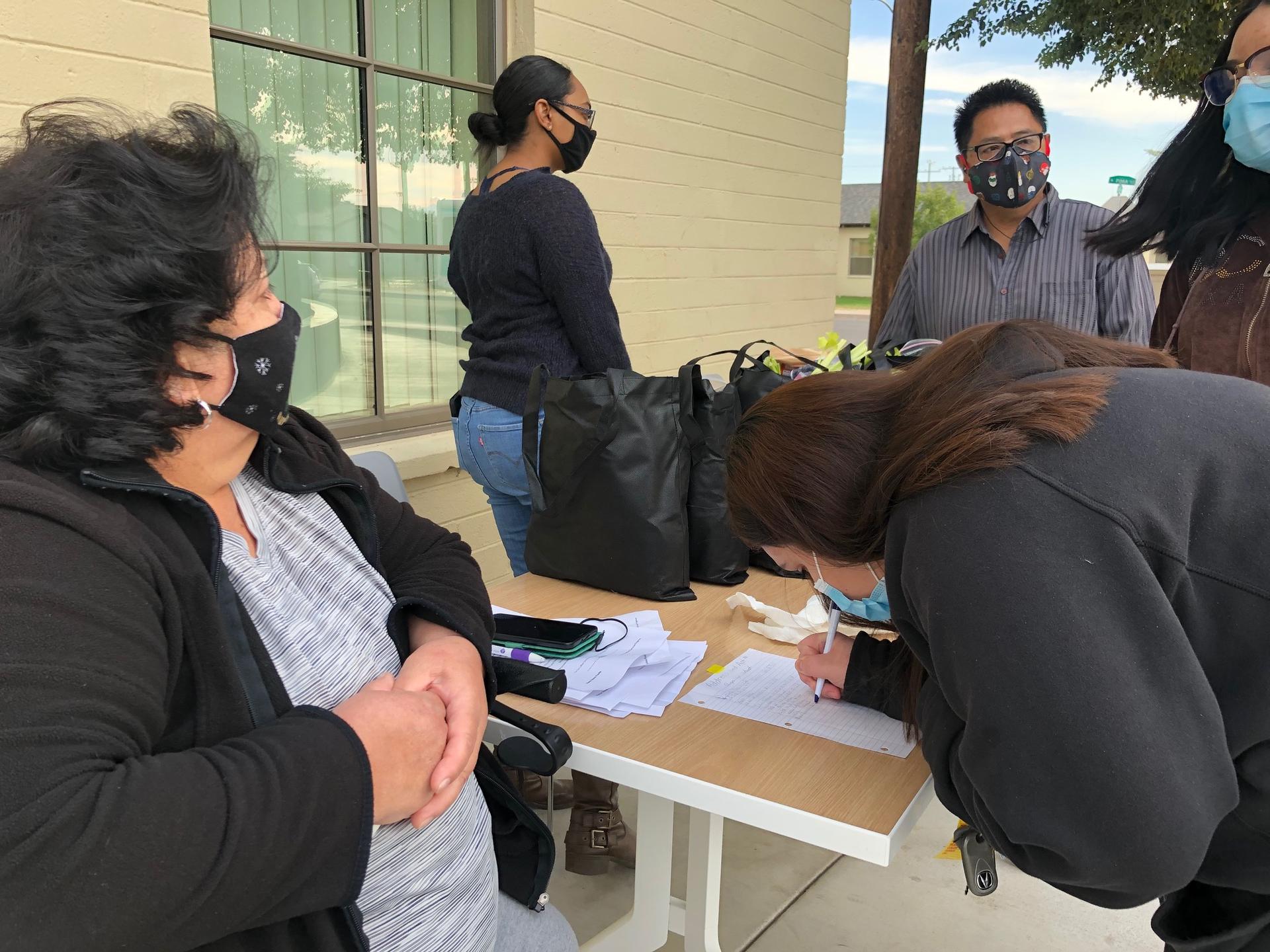

During a recent drive-through offered at their offices in central Phoenix, the collective gave away hundreds of organic food packages featuring Indigenous products, including tepary beans and wheat berries from Ramona Farms, a family-owned farm in Sacaton, Arizona; blue corn from the brand Pinole Brew that comes from the Tarahumaras Indigenous community in Chihuahua, Mexico; and fair trade coffee from the Quetzal Co-Op in Phoenix, imported from Mexico.

The collective has shared these packages thanks to a grant from the city of Phoenix with Affordable Care Act funds. The goal is to reach Indigenous, immigrant and communities of color — those hit hardest by the COVID-19 pandemic.

A lot of immigrant communities in the US might be disconnected from some of these ancestral foods due to colonization, but when eaten, it can tap into the body’s genetic memories, Parra said.

“This is what corn is supposed to taste like. This is what beans are supposed to taste like. You know, this is what our ancestors did with corn. And so it’s kind of just reshowing, reintroducing it and maybe even giving people a little bit of curiosity, like, what else did my family eat?” she said.

Food like this isn’t found everywhere in Phoenix and can be expensive. Part of the message from the collective is that having access to nutritional foods is a human right that holds a person’s dignity intact.

Related: Food waste increases during the pandemic — compounding an existing problem

“The nutritional content of our care packs mean the world of difference when it comes to healing our body, using this food as medicine, treating it as medicine and thinking how can this help me?”

“The nutritional content of our care packs mean the world of difference when it comes to healing our body, using this food as medicine, treating it as medicine and thinking how can this help me?” Parra said.

Eating Indigenous foods like her mom used to eat helped Parra, too, during bouts of diabetes in her first pregnancy and preeclampsia, in her fourth. She said they helped her heal and this inspired her to open up her own food business, Sana Sana, to share those benefits with others. During her postpartum time, five years ago, she also received a lot of support from other women — and together they founded the Cihuapactli Collective.

One of them is Enjolie Lafaurie, a psychologist, who also works as a death doula, a guide who helps people with their transition from life to death.

“Now in the time of COVID[-19], where death and loss and grief are so in our faces, [it’s] so important to us,” Lafaurie said. “So, maybe food is the entry point … But then you get to know the real stuff. Right? What’s in the background and what’s impacting them. And then, here we are able to offer some other services or support for them.”

Related: Pandemic exposes ‘major vulnerabilities’ in US food system

Online yoga and workshops on women’s health are just some of those services the collective has been organizing in partnership with others. They are also supporting small businesses. Ramona Button, who runs the Ramona Farm in Arizona, contributed beans and wheat berries to the food packages as a way of passing on Indigenous traditions shared with her from her father.

“With this pandemic, we become spiritual again. Because of the losses, we can’t be with our relatives, our loved ones. … And especially our elders now. They’re going — who is going to tell us these things? It was never written in the books.”

“With this pandemic, we become spiritual again. Because of the losses, we can’t be with our relatives, our loved ones,” said Button, a member of the Akimel O’Odham Indigenous nation. “And especially our elders now. They’re going — who is going to tell us these things? It was never written in the books.”

Since September, the collective has reached 1,500 families with food packages, but they estimate the number is higher since they started doing this work in March through smaller community grants. They’ve reached mostly elderly people and underresourced families.

On a recent Friday, a group of volunteers gave away the Indigenous food care packages at Coffelt, an affordable housing community with 301 families in south Phoenix.

Luz Mata, a longtime resident and volunteer, took charge of the Christmas music, a mix of Latin American traditional songs in Spanish with a twist of salsa.

“I love giving out food at this time of the year,” she said.

Mata raised her children in Arizona, and like many in this housing community, she has family from Mexico. Mata really enjoys the coffee that comes in the bag.

Some residents are not so familiar with the ingredients but that’s often an excuse to talk to neighbors who do know how to prepare them, said Vivian Diaz, a resident services coordinator for the Housing Authority of Maricopa County.

“If this food connects them, that’s a perfect outcome for me,” Diaz said.

For Miguel Rodriguez, originally from Mexico, another volunteer and neighbor, the packages will bring much-needed food to his family of seven. Rodriguez works recycling metal and during the pandemic, he’s worked less, which means lost income.

“It’s sad that we won’t be able to gather with family to prepare these dishes … enjoy a pinole … atole, a chocolate. You can’t do it,” he said.

Yet, the food in the bag takes him back to his childhood, to his grandparents’ farm and freshly harvested corn.