New Washington law on religious accommodations could serve as model for other states

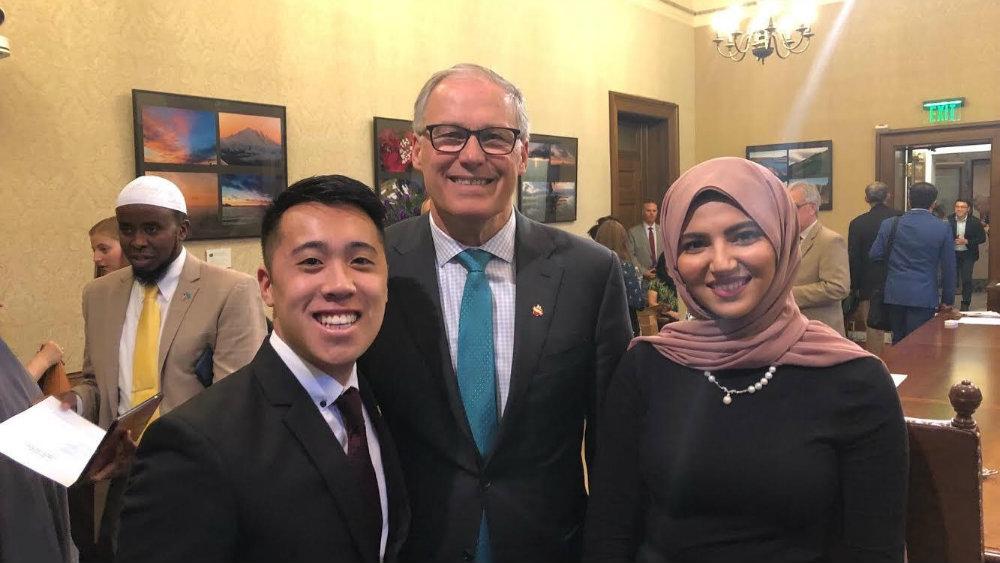

(Left to right): Byron Dondoyano Jr., Washington Gov. Jay Inslee and Mennah El-Gammal during the signing of SB 5166, legislation that requires higher education institutions to provide “reasonable accomodations” for students observing a religious holiday. The bill goes into effect July 1.

Back in 2017, two professors at the University of Washington Bothell decided to offer their students the option to take exams at night, from 10 p.m. to midnight. It was finals week, and some Muslim students were fasting from food and water for approximately 14 hours daily, from sunrise until sundown, for the holy month of Ramadan.

Bryan White, a biology professor, and Rania Hussein, a professor of electrical engineering, thought having tests at a later time would allow students to observe the holiday, break the fast and regain their energy in time for their tests. White said he was concerned that students fasting may have trouble with concentration during exams because of blood sugar levels.

Hussein, who is Muslim and came to the US from Egypt in 1998, said she used the time as an opportunity to build community with her students — Muslims and non-Muslims alike. She arrived at the exam room with food at sundown — around 9 p.m., an hour before testing began — and invited students to break their fast with her.

“I wanted this to be an example of diversity in action, where students can share their culture,” said Hussein, who now works at UW’s Seattle campus. “It wasn’t just an exam to me. It was a nurturing environment that we, as educators, strive to provide to our students.”

“It wasn’t just an exam to me. It was a nurturing environment that we, as educators, strive to provide to our students.”

Hussein and White’s night exams sparked a conversation about religious accommodations for students. Shortly afterward, students at another UW campus drafted and lobbied for a bill requiring religious accommodations within higher education institutions. Washington Governor Jay Inslee, who is running to be the Democratic nominee in the 2020 presidential election, signed it into law in April; it goes into effect in July. Advocates say the law is unique in its scope and how it addresses religious accommodations at higher education institutions. They plan to use it as a model to advocate for similar laws in other states.

Washington’s law, which applies to all religions, requires faculty at higher education institutions to “reasonably accommodate” students who are observing a religious holiday and expect to be absent or endure hardship because of it. This means working with students to reschedule a test or offering alternate exam times. Students need to request an accommodation within the first two weeks of the course, and faculty must put information about accommodations on the syllabus.

Supporters of the law say it’s a way to ensure that students of all faith backgrounds can practice their beliefs without it conflicting with academics.

“[Students] don’t have to compromise or choose between being who they are and fulfilling their academic requirements,” Hussein said of the Washington law. “They don’t have to feel uncomfortable showing their religious identity because they would see that the state is supportive of them.”

How campuses deal with religious accommodations

Religious accommodation rules vary from campus to campus and come in different forms.

This year, the issue came to the forefront because final exams, once again, coincided with Ramadan. The holiday falls at different times every year because it follows the lunar calendar. This year, the monthlong holiday began May 4 and is set to end this week.

Many universities around the country have policies requiring “reasonable accommodations” for students fasting during Ramadan. Some extend dining hall hours or provide more options for religious dietary restrictions. Others send out notices about accommodations to faculty.

But when it comes to testing and classroom activities, such as lab work or class presentations, many faculty members don’t know the rules or don’t uphold them, says Cody Nielsen, the founder of Convergence On Campus, a group that promotes equity among religious, secular and spiritual identities at US universities. Nielsen said a state law, especially one requiring faculty to put information on the syllabus, formalizes and enforces religious accommodations.

“The power of this being placed in syllabi is more than just about making sure that people have a religious accommodation, it’s about a visible demonstration of the university’s values as it relates to your religious and non-religious identity,” Nielsen said.

From campus to the state capitol

Washington’s law is the result of an effort by students, professors and interfaith groups — one that’s become a lesson in empowerment and the importance of advocacy.

After getting positive feedback from her students in 2017, Hussein spread the word about the alternative exam times through a program she founded, the Many Cultures One Community program at the Muslim Association of Puget Sound.

“I facilitated media coverage for this story to raise awareness and to get this idea out to the community at large and make it popular and take our example for others to follow in higher education,” she said.

Byron Dondoyano Jr., a student at the University of Washington, Seattle, took notice of what happened at the Bothell campus and brought the idea for a statewide law to his classmate Mennah El-Gammal, who at the time represented Middle Eastern students in student government.

At first, El-Gammal was skeptical the idea would go anywhere. She said 2017 was a difficult time for many in the Muslim community: US President Donald Trump had just been inaugurated, and his administration instituted a travel ban for travelers from several Muslim-majority countries.

“Students of faith and especially Muslims, because of their high visibility, often feel a sort of cultural silent pressure to not further alienate themselves or burden or be a cause for a burden on campus,” she said.

“Students of faith and especially Muslims, because of their high visibility, often feel a sort of cultural silent pressure to not further alienate themselves or burden or be a cause for a burden on campus,” she said.

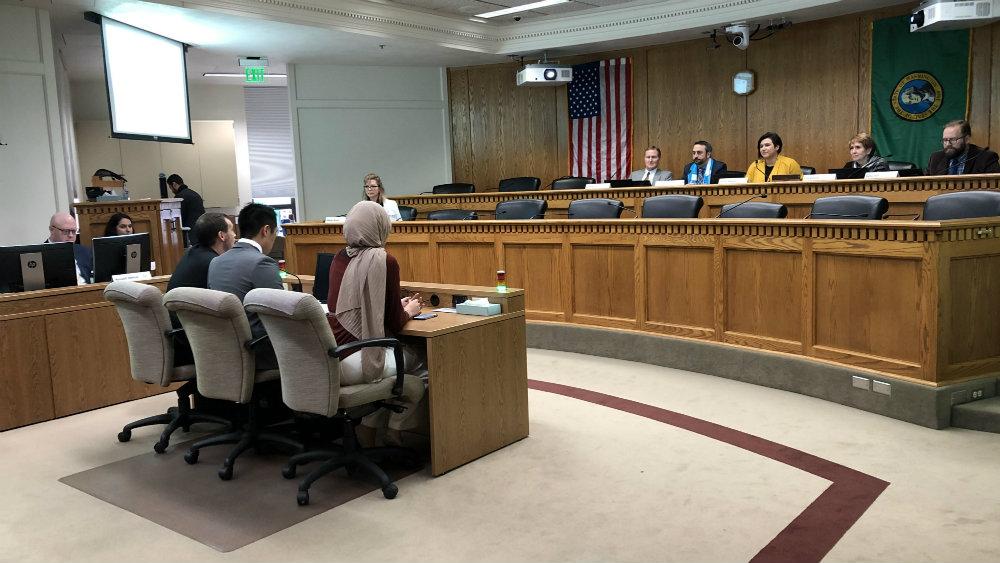

Dondoyano and El-Gammal pushed for a religious accommodation bill through the university’s student senate and then took their idea to the state legislature. Students, community groups and professors testified before lawmakers about why it’s important to have an accommodation policy.

“I think one of the biggest lessons was that it’s very possible to imagine something different and imagine a different world that is more pluralistic,” said El-Gammal.

El-Gammal said lobbying the state legislature has helped her realize the importance of self-advocacy and activism and to push for policies that reflect “representation in ways that have institutional memory.”

Dondoyano emphasizes that the law is for students of all faiths — for example, Orthodox Christians who observe Christmas in January or Jewish students who have finals on Saturday, the Jewish Sabbath.

Religious accommodation efforts across the US

Elsewhere around the country, students worked with campus officials to accommodate students taking final exams during Ramadan this year.

Cornell University in New York extended its dining hall hours, and facilities provide boxed meals for students’ suhoor, the pre-dawn meal. Yahya Abdul-Basser, president of the university’s Muslim Educational and Cultural Association, said an administrator also helped create a letter template that would help students make accommodation requests to their instructors. Cornell has its own religious accommodation policy.

“Testing slots that exist here are either early in the morning or late at night, during that time when people kind of crash, or they overlap with when we break our fast and so we’d have to break our fast in the middle of a test,” Abdul-Basser said.

Accommodation policies tied to religion can bring controversy. Critics worry that students could abuse such policies — making frivolous requests or claiming to be part of a religious practice to get out of taking a test. There’s also the issue of logistics, resources and wariness over policies that dictate what instructors should do in a classroom.

“I can understand why it seems daunting and hard, but I think people will realize it is much easier than people’s worst fears,” said White, the UW professor.

And advocates of the Washington law say faculty members already provide accommodations for students in other cases: those with disabilities may need to have more time taking an exam, or athletes traveling with their teams may need to reschedule a test. There’s also worry that policies cross the line that separates church and state within public universities.

To those worries, El-Gammal said: “We have Christmas instituted into all of our holidays all of our breaks, for school, for work. That’s just a reflection of the majority, it’s not a reflection of … secularism.”

The Washington law goes into effect in July, which is after Ramadan and finals for UW, but students say they want to make sure that universities properly implement the law in the future. There are plans to introduce similar bills in other state legislatures around the country.

Hussein hopes to also advocate for the law to be extended to K-12 schools. She said students in high school, sometimes have to take the SATs or AP tests during Ramadan.

“I realized that the students in K-12, also face similar challenges,” she said. “I am hoping that this law becomes a federal law to provide accommodation to all students of all faiths across the United States.”