Bahrain becomes flashpoint in relations between US and Saudi Arabia

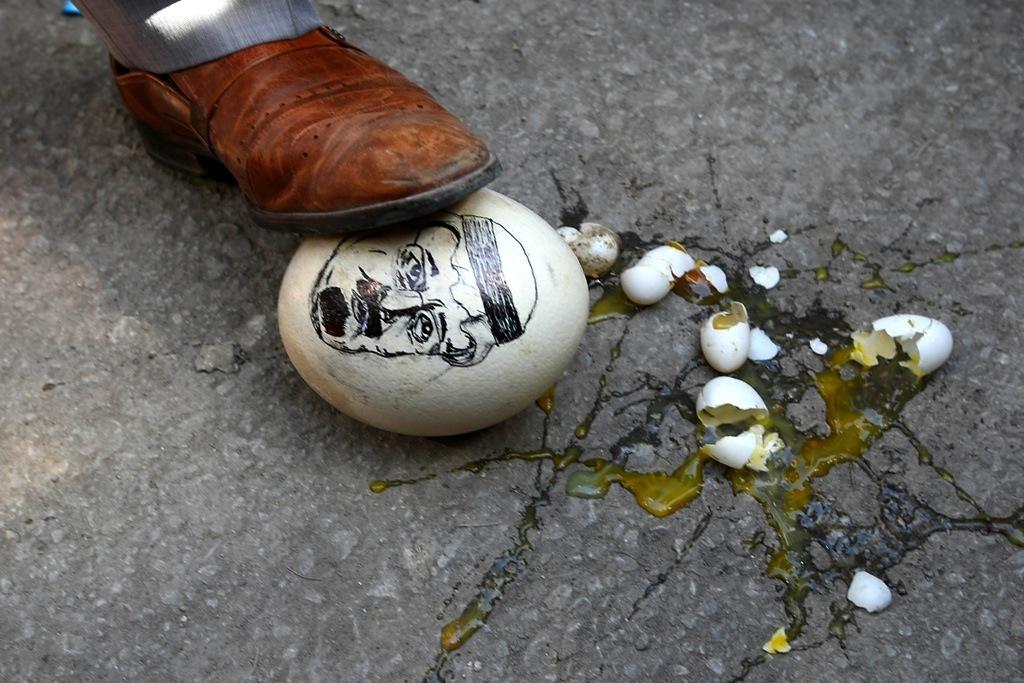

A demonstrator steps on an ostrich egg with a drawing of Saudi Arabia’s King Abdullah on March 17, 2011 in front of the Saudi Arabia Embassy in Ankara as he attends a demonstration in support of mainly-Shiite demonstrators in Bahrain and denouncing the intervention by Saudi troops.

MANAMA, Bahrain — In the final hours before government forces rolled out their brutal crackdown on Bahrain’s pro-reform protesters last month, a senior U.S. diplomat worked feverishly to broker an agreement that could have led to negotiations between the ruling royal family and the opposition.

The last-ditch efforts of Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs Jeffrey D. Feltman fell through for several reasons. One of his key interlocutors, Bahrain’s crown prince, became unavailable at a crucial point. In addition, the hour for compromise ran out as government hard-liners set in motion their plans to crush the protest movement.

Saudi troops had been called in. A state of emergency was declared even as Feltman was meeting with the opposition. And police and military were getting their kits ready for the decisive, dawn sweep into Pearl Roundabout, the protesters’ staging grounds.

(Read: Why Bahrain's protests movement failed)

Feltman also was up against another barrier to success: Saudi Arabia.

The kingdom, which regards Bahrain somewhat like the United States regards Puerto Rico, had no desire for Feltman to succeed because in Riyadh’s view, any negotiations would likely involve a dilution of the royal family’s monopoly on power, setting a distasteful example for other Gulf monarchies.

The Saudis basically “weren’t going to take seriously anything Feltman was trying to do, especially since he was pressuring [the Bahraini government] at all costs to sit with the opposition,” said a Gulf diplomat who declined to be identified because he was not authorized to speak to the media.

The Saudi position on Bahrain, he added, is “no weakening of the monarchy.”

The tiny island, which has been a base for the U.S. Navy’s Fifth Fleet for more than half a century, has become and will likely remain an outsized flashpoint in Saudi-U.S. relations.

Riyadh and Washington both regard Bahrain as a key ally in securing the Gulf’s vital sea lanes and in containing potential threats from Iran. Both also have an interest in ensuring that Iran not gain a foothold among Bahrain’s discontented Shia, who make up at least 60 percent of its population but have little say in the Sunni-controlled government.

This sectarian divide in Bahrain is Saudi Arabia’s primary concern. Riyadh believes that any reforms that would give enhanced powers to the Shia majority would be seen as a "win" for Saudi Arabia’s archrival, Iran. They also fear that this would embolden the kingdom’s own Shia minority, which also complains of being treated as second-class citizens.

Having watched with dismay as Iran became an influential player in Iraq after the Shia majority there took control of the government, the Saudis are not about to let that be replicated in Bahrain.

So they were not happy to hear the administration of U.S. President Barack Obama criticize Bahrain’s assault on the protesters in mid-February, which left seven dead, nor its urgings that the royal family considers serious political reforms.

To show their displeasure, the Saudis declined to receive Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and Secretary of Defense Robert Gates for visits in Riyadh.

Having strained relations with the top consumer of U.S. military hardware is not an agreeable situation. Saudi Arabia has plans to purchase up to $60 billion in arms from the United States over the next decade

As a result, Washington did not publicly criticize Saudi Arabia’s military intervention in Bahrain. And it has offered only lukewarm rebukes to Bahrain about the fierce repression being inflicted on the Shia population since the crackdown began on March 16. So far, there have been about 20 deaths and nearly 400 imprisoned, according to human rights groups.

In a sign that this U.S. reticence is appreciated by Riyadh, Gates was belatedly received by King Abdullah bin Abdul Aziz on April 6. And six days later, White House National Security Adviser Tom Donilon met with the king in Riyadh.

But this stance is tarnishing the U.S. image as a promoter of human rights and democracy.

“It does appear that the U.S. is picking its battles in the region and standing up for the protesters is not a priority,” said Jane Kinninmont, an expert on Bahrain at the London think tank, Chatham House. “I don’t see any meaningful opposition from the United States to the Saudi position on Bahrain.”

Kinninmont noted that Bahrain has never seen much anti-American sentiment.

“But you could definitely see that sentiment rising in the future,” she warned. “And that definitely is a concern in a country where the United States has a major naval base.”

The days leading up to the March 16 attack on the Pearl Roundabout were filled with drama, sometimes in plain sight and sometimes not.

(Read: Bahrain protest movement stifled by government suppression)

On the morning of Sunday March 13, the capital of Manama awoke to barricades on the main highway blocking the city’s financial district. This move by a radical faction of protesters outraged the government, particularly royal family hard-liners, or “Falcons,” as they are known here.

Led by Prime Minister Khalifa bin Salman Al Khalifa, who has been in his job for 40 years, the hard-liners saw this as another notch in the increasingly provocative posture of militant protesters who had days earlier organized marches on royal palaces.

On top of this, the Falcons and their allies in Riyadh had been alarmed to hear Gates telling reporters a day earlier, on Saturday, that he had urged a faster pace toward serious reforms in his meetings that day with Bahrain’s King Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa and his son, Crown Prince Salman bin Hamad Al Khalifa.

“His remarks went down badly in Riyadh,” said one Saudi source.

Around mid-day Sunday, King Hamad called Saudi Arabia’s Foreign Minister Prince Saud Al Faisal and requested Saudi troops. King Abdullah quickly agreed.

“The government of Bahrain called for the Saudis because they felt the need for regional backing against U.S. pressure” to negotiate with the opposition, said a Bahraini professional who declined to be named.

“My analysis,” he added, “is that the Saudis were very panicked when Hosni Mubarak fell down … They felt the flames of the Egyptian revolution are spreading.” As a result, “they are very strong behind limiting the size of changes” in Bahrain’s political system.

Meanwhile, the Crown Prince, who Bahrainis regard as the royal family leading dove, or Pigeon, as they are known here, issued a list of seven topics to be discussed if the Shia opposition parties would agree to start talking without preconditions. He also said that any agreement reached could be put to a referendum.

Also on Sunday, Chibli Mallat, a constitutional lawyer and visiting professor of Islamic studies at Harvard Law School went to Logan airport for his flight to Bahrain. As he checked in, his phone rang and Mallat was told to cancel his trip because of deteriorating conditions.

In an interview, Mallat said he had been invited to Bahrain by the opposition, with the encouragement of the U.S. State Department, in order to discuss various issues related to the opposition’s proposal for a constitutional monarchy in Bahrain.

“Somehow,” said Mallat, “on the 13th things started going wrong.”

On Monday, about 1,200 Saudi National Guard troops drove a long convoy of armored cars across the four-lane, 16-mile causeway linking their country to Bahrain. Five hundred policemen from the United Arab Emirates followed. The forces were described as a contingent from the six-nation Gulf Cooperation Council that was rushing to the defense of one of its members.

It was the first time the Gulf Cooperation Council intervened in a domestic dispute of a member. The Saudis officially informed U.S. officials of their decision to send in troops on Monday.

Meanwhile, even as foreign troops entered his country, Crown Prince Salman had not given up trying to coax the moderate Shia opposition into talks.

On Monday, he sent four intermediaries to a late afternoon gathering of opposition figures from several parties at the headquarters of Wefaq National Islamic Society, the largest and most influential group, according to Abdulnabi Salman, deputy secretary general of the Democratic Progressive Tribune, a small party comprised mostly of former communists.

The intermediaries urged the opposition to be flexible, help the crown prince out and accept a dialogue immediately. But the opposition remained skeptical and mistrustful. It wanted to know who they would be negotiating with and if he would accept an elected constituent assembly to write a new constitution. The emissaries of the crown prince asked if he did, would they accept that it made decisions on a two-thirds vote rather than a simple majority.

The meeting ended inconclusively.

(Read: Bahrain mired in a dangerous stalemate)

Also on Monday, Feltman arrived. It was his fifth visit to Bahrain since the protest movement began on Feb. 14. According to senior Wefaq officials, he and embassy officials met with the opposition that night.

“The embassy people were complaining about our delaying” in accepting the crown prince’s offer of dialogue, said Abdulnabi Salman of the Tribune party. “We told them about our reasons for our lack of confidence,” he added, referring to past promises from the government to enact political reforms that went unmet.

On Tuesday, Feltman met with the Crown Prince in the morning, according to a State Department official. Then, in the afternoon, as King Hamad was declaring a state of emergency and curfew, Feltman met again with Wefaq officials.

He was trying to hammer out some kind of accommodation that would allow talks on political reform to get underway. It is not clear exactly what his proposal was. Some sources describe it as a “mediation” proposal. Others say it was like “a code of conduct” to restore order to the capital’s increasingly lawless streets so that a genuine political dialogue could start.

Wefaq leader Sheikh Ali Salman said in an interview with three of his top aides that they accepted Feltman’s proposal and that the U.S. diplomat said he would get back to them after obtaining the assent of the Crown Prince.

But late Tuesday evening, they said, they were told that Feltman still had not be able to reach the king or crown prince.

“Feltman was trying, according to our information, to get any response from the government and nobody was responding,” said Wefaq’s Abdul Jalil Khalil Ebrahim.

“My guess is that the king and crown prince had nothing they could say to Feltman, because Saudi Arabia was calling the shots at that stage,” said Augustus Richard Norton, a Middle East scholar at Boston University.

Hours later, at first light on Wednesday morning, government security forces swept through Pearl Roundabout, arresting those who did not flee and ripping down all evidence of the protesters’ presence.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!