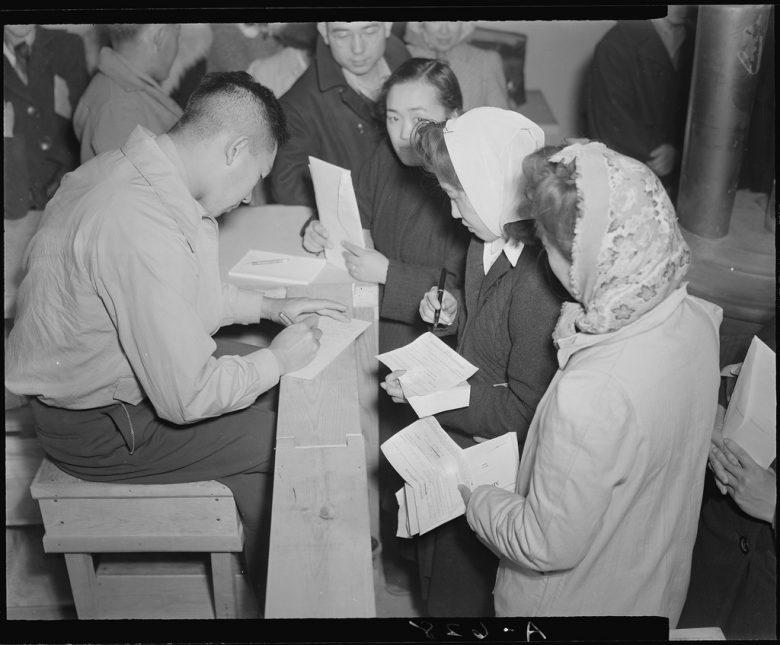

Original caption from the War Relocation Authority: San Bruno, California. Here a line is seen waiting to enter the building where they will cast their votes for Councilman from their precinct. A general election for five members of the Tanforan Assembly center Advisory Council is being held on this day. This is the first time Issei have ever been able to vote because of American Naturalization laws. June 16, 1942.

Nearly 75 years ago, 120,000 Americans of Japanese descent were stripped of their rights and property under the guise of national security.

They were packed into trains and buses and moved from their West Coast homes — to temporary holding stations at fairgrounds and racing tracks, and then to permanent camps in remote parts of Idaho, California, Utah, Arizona, Wyoming, Colorado, Texas and Arkansas. Though several cases challenging the legality of this imprisonment made it all the way to the Supreme Court, only a single ruling favored the Japanese American petitioners.

It might come as a surprise, then, that they retained a key tenet of citizenship for the duration of their incarceration: the right to vote. However, between racially motivated interventions and inadequate voter education, this right was only nominally intact.

Absentee voting had existed in some form since 1652, but World War II marked the first and only time in US history that states had to make large-scale arrangements for an incarcerated civilian population to cast votes in absentia. The result was a hodgepodge of rules and regulations that effectively disenfranchised the Japanese American electorate.

One of the first questions to confound wartime voting planners was where exactly the civilian incarcerees should vote. In California, the state with the highest population of displaced Japanese Americans, the constitution stipulated that residence had to be “of choice” in order to qualify for voter registration. It was plain to all that the prison camps were anything but residences of choice. As a result, Japanese Americans were instructed to vote in the precincts where they’d lived prior to incarceration. Other states with camps, fearful of the influence these “enemy aliens” might have on local elections, enacted similar regulations.

By August 1942, the Wartime Civil Control Administration released a policy statement announcing that “qualified citizen evacuees” — the people held in camps — were entitled to the same absentee voting rights as any other citizen who was unable to be present at his or her registered polling place. But states and counties were left to grapple with what exactly those absentee voting rights were in this unprecedented scenario.

Even as the logistics of voting and other basic facets of civilian incarceration were being sorted out, an editorial in the newly minted Tanforan Totalizer urged residents, many of whom were living in old horse stalls at that race track-turned-prison, not to let their “civic consciousness atrophy”:

“As citizens who hope to return eventually to normal roles in the American scene, it is highly important that we exercise all such rights and privileges of citizenship as will make our return seem less another abrupt transition than a continuation of accustomed practices.”

Civic duty aside, many Japanese Americans felt that they had no choice but to cast a ballot. Election laws stipulated that voter registration would automatically expire if an individual failed to vote in even a single election cycle. However, as incarcerees prepared for the impending midterm elections, they had limited awareness of the issues and candidates due to lack of access to news sources. To make matters worse, new voting regulations prohibited electioneering in the camps.

From Utah’s Topaz concentration camp in November 1942, Doris Hayashi wrote in her diary, “I haven’t been able to do any reading on these issues so it was rather blind voting for me.” A fellow prisoner, Charles Kikuchi, had a similar experience: “I did not know much about the local issues, so I left most of them blank. … California politics are so distant to me now. I wonder how my interest in such things will be with the passage of time.”

Though 2,000 absentee ballots were sent to voters in multiple relocation centers in the fall of 1942, Kikuchi wrote, “A Los Angeles report claimed that less than 100 Nisei voted in that city, but this figure seems much too low. There must have been over 100 L.A. Nisei voters in this camp alone that cast their ballots.”

The discrepancy that Kikuchi noted points to yet another impediment to voting rights for wartime incarcerees. At least one report mentioned poll watchers challenging “every ballot sent in by anyone with a Japanese name” on the false grounds that Japanese Americans held dual citizenship with Japan and therefore could not vote in US elections. It’s impossible to know how many ballots sent from the camps were thrown out due to race-based meddling at the polling stations. But what is clear is that the opposition was colored by the same currents of racism and bigotry that led to Japanese American incarceration in the first place.

Ballot box interventions were likely influenced by the Native Sons of the Golden West, a group that sought to strip all non-white Americans of their citizenship. This white supremacist organization had stoked anti-Japanese American sentiment in the decades leading up to World War II, and was a major proponent of mass incarceration after Pearl Harbor.

In 1942 and '43 the Native Sons joined forces with the American Legion to sue San Francisco County’s registrar of voters, Cameron H. King, in an attempt to remove Nisei names from the voter rolls and to prevent them from voting for the duration of the war. As reported in the Rohwer concentration camp newspaper, they contended that “dishonesty, deceit, and hypocrisy are racial characteristics of the Japanese” and that this made them “unfit for American citizenship.”

The parties argued their case, Regan v. King, in California’s Federal District Court. Representing the Native Sons, former California Attorney General U.S. Webb made the brazenly bigoted argument that the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution were made entirely “by and for white people.” The federal district judge rejected the Native Sons’ plea, but the case moved up to the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals. There it was quickly dismissed on the precedent of the 1898 Wong Kim Ark Supreme Court decision that had determined US citizenship for all American-born individuals. Relentless in his efforts to advance the case, Webb attempted to bring it before the Supreme Court, but they refused to hear it.

The American Civil Liberties Union saw parallels between this case of racist nativism and their own fight for black voting rights. In response, they lent support to the defense and spurred the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) into action once the case reached the 9th Circuit. African American lawyers also served as counsel to the JACL in their drafting of the amicus brief that helped overturn the case. This alliance would carry over into post-World War II civil rights advocacy that eventually led to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Also: Despite history, Japanese Americans and African Americans are working together to claim their rights

The landmark case also firmly established the rights of all Americans to birthright citizenship. As defendant Cameron King later wrote, “Japanese ancestry is immaterial” when it comes to citizenship rights and “they are entitled to exactly the same rights as all other citizens.” King went on to note that “the law makes no discrimination against any citizen because of ancestry."

By the time of the 1944 presidential election, Japanese Americans had been imprisoned for a full two years. Once again, questions arose about where the incarcerees ought to register to vote. The Wyoming Attorney General issued a statement announcing that his state’s voting rights would not be extended to those incarcerated at Heart Mountain. With other states sharing his view, it was ultimately determined that all incarcerees should again register in their precincts of origin since they did not meet the legal requirements for establishing domesticity in the states where they were imprisoned. But once again, complicated rules would have made it inordinately difficult to cast a ballot.

Among other regulations added in 1944, The Poston Chronicle reported that in applying for an absentee ballot, individuals needed to “make clear that the voter means to keep the state of California as his permanent home and will return when able.” Voters were also required to return ballots within a narrow window — “not more than 20 and not less than 5 days before election day.” Considering that California was not hospitable to returning Japanese Americans and the inconsistency of mail service, these rules would have stacked the odds against those wanting to vote.

California’s Attorney General Ted Hass also acknowledged that the voting law might be enforced arbitrarily. As reported in The Gila News-Courier, “probably the different county clerks will act in different ways upon receipt of such applications [for voter registration]. Some may take the mistaken view that the evacuees are no longer legal residents of the state.”

Though the courts had struck down the overtly racist appeals to deny Japanese Americans the right to vote, restrictive rules like these quietly excluded them from fair participation in the electoral process.

While the circumstances of Japanese American incarceration were unique, this type of race-based voter disenfranchisement echoed throughout marginalized communities in America, most notably in the Jim Crow South where black citizens were routinely kept off the voting rolls. The desire to obtain fair and equal access to voting rights was central to the Civil Rights Movement. And activists like Yuri Kochiyama and William Marutani drew upon their own experiences of injustice during the war years to support the struggle for black civil rights.

In one of the crowning achievements of the Civil Rights Movement, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Author Ari Berman notes that the act “quickly became known as the most important piece of civil rights legislation in the twentieth century and one of the most transformational laws ever passed by Congress.” Theact ended some of the most egregious forms of discrimination that had plagued black voters, and improved voting equity for other minority groups through amendments enacted a decade later. But even that did not eradicate the practice of voter discrimination in its entirety. Congress renewed the act in 2006 (and several times before then in 1970, 1975, and 1982) after hearing testimonies that proved the continued, widespread presence of racial discrimination at the polls.

Even so, the Supreme Court decided to invalidate key parts of the Voting Rights Act in 2013 on the grounds that, as Chief Justice John Roberts wrote, it was “based on 40-year-old facts having no logical relationship to the present day.” Though voting discrimination might not be as overt as it was during World War II incarceration or in the Jim Crow South — though the case has been made that, indeed, it is that bad — the threat of widespread race-based voter disenfranchisement is once again a reality.

As we move toward one of the most polarizing presidential elections in recent memory, new laws intentionally discriminating against voters of color have cropped up across the country. It’s impossible to predict exactly how many voters will be disenfranchised, but it could easily be enough to decide the election.