Is the US ready for the next big pandemic?

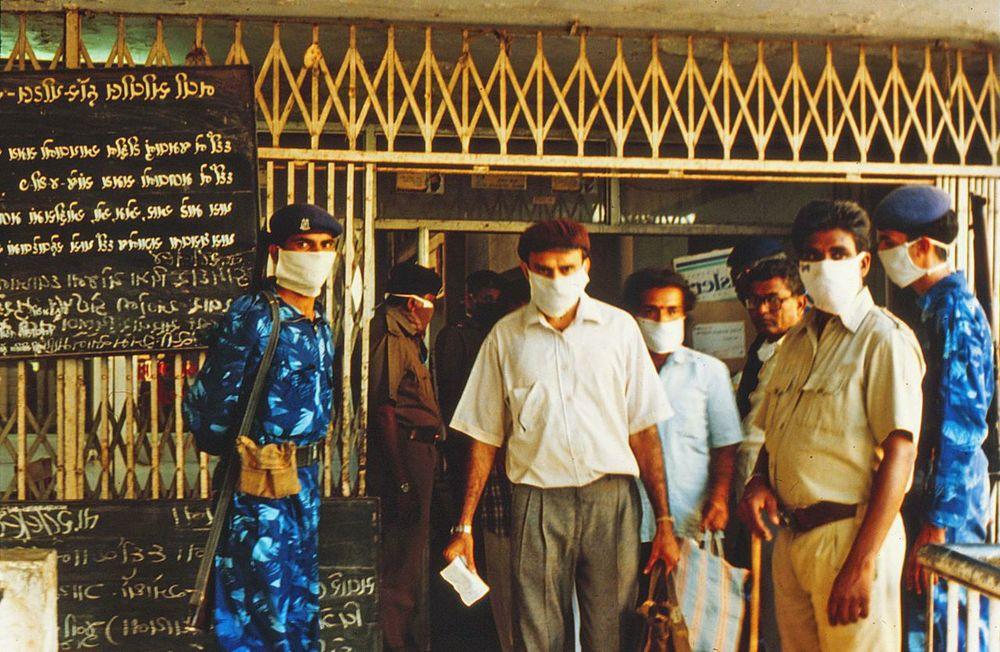

The Indian military enforcing a quarantine of Surat’s hospital in 1994, during an outbreak of plague in that city. Photo by Laurie Garrett

In 1994, public health experts Laurie Garrett and Stephen Ostroff warned of disturbing trends in global public health: Rising antibiotic resistance, overlooked and underfunded public health infrastructure and a frightening resurgence of old diseases we thought we’d beat.

More than 20 years later, they say many of the threats to our public health, including the threat of a massive epidemic, remain the same.

“Back in 1994 … it was a controversial premise — the notion that we had not defeated infectious diseases, that they would surge back, that we were not comfortably in the age of just thinking about cancer and heart disease,” says Laurie Garrett, senior fellow for global health at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York, “That has completely changed and I think now, from the highest levels of government right on down, people realize that we had a major hubris problem back in the day and that the microbes are constantly mutating and posing new challenges.”

The possibility of epidemic in a highly globalized world, however, is not the only threat to public health. Antibiotic resistance is another issue Stephen Ostroff, acting commissioner of the US Food and Drug Administration, says he’s worried about.

This isn’t the first time he’s sounded the alarm. In 1994 he told Science Friday, “we're getting into a situation where we went from the pre-antibiotic era, to the antibiotic era, to the post-antibiotic era.”

Now, he says, the post-antibiotic era may have actually arrived.

“This is a really serious and growing problem,” Ostroff says, “Even at the highest levels of government, you hear now President Obama talking about this, you hear leaders in Europe and the World Health Organization talking about that particular topic. So I'm very hopeful that, with this recognition, that there really is the potential with appropriate investments of resources to be able to do something about this.”

Public health threats, however, are not just related to pandemics or new strains of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Garrett says what she worries is the way politicians and the public think about threats.

“That's the story of public health: whack-a-mole,” Garrett says. “We continue to have two trends that just constantly re-emerge: one is government saying, ‘Let’s kick that down the road. You know, we'll deal with it when it's in our face. But we don't really want to put time, energy and money into it before catastrophe.’ And the second is that, when catastrophe hits, the public goes berserk. And every single time the conspiracy theorists come out of the walls … and mobilizing wacko politicians and so on, over and over. And that's true in every country in the world — that's not a uniquely American phenomenon.”

Ostroff agrees: “We still suffer from a phenomenon of seeing large amounts of resources devoted to a problem while it's very highly visible and everyone is paying attention to it. But the difficulty tends to be sustaining those resources over time.”

Instead of a reactive approach, Ostroff and Garrett say the US should be proactive.

“The important issue is making sure that we sustain the infrastructure that's necessary all the time because, as you know, these problems tend to come up over and over again and I think that they will continue to do so,” Ostroff says.

This article is based on an interview that aired on PRI's Science Friday.