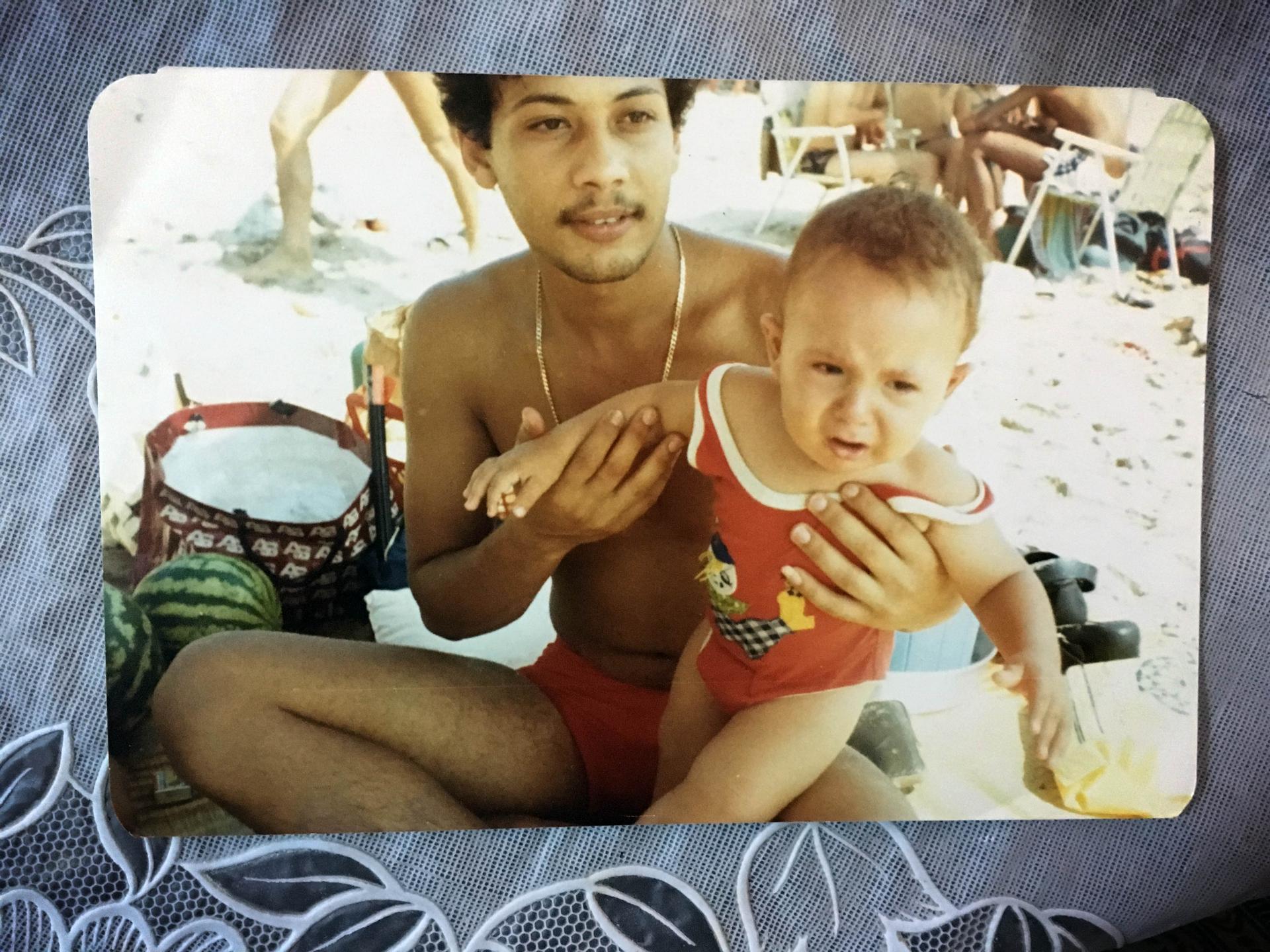

Samia Abdullah holds up a picture of her brother Emad who disappeared in 1984 when he was 20 years old. His family thinks he's still alive in a Syrian prison.

The last time Samia Abdullah saw her brother Emad was 1984 when Lebanon was gripped in civil war.

Emad had left her home in Beirut to go to the northern Lebanese city of Tripoli.

On the way back, he vanished. He was 20 years old.

Rumors spread that Emad was stopped at militia checkpoint and taken to Syria, which had intervened in the conflict. For decades Samia and her family looked for answers. One of her brothers even went to Syria to try to find him, but Syrian authorities maintained they didn’t have Emad Abdullah in custody.

“Nobody helped us. Nobody in the government, nobody help us,” Samia Abdullah says.

Then in 2003, the Abdullah family got a letter they believe was from Emad, written with burnt matchsticks and smuggled out of a Syrian prison.

“[It] said ‘please my father, my mother, please help me. I miss you. I am sick,’” Samia recalls.

In some ways, the Abdullahs are lucky. At least they have at glimmer of hope that Emad is still alive, in a Syrian prison.

Lebanon’s 15-year civil war ended in 1990, but as many 17,000 people remain missing. Some people were taken by militias or government forces at checkpoints; others simply never returned from a trip to the store.

“Most of the families would say, ‘he went out to get a cigarette, to get some food, to visit someone, to bring something that he forgot from the car and that was it,’” says Reem el Soussi, a project manager with the group, ACT for the Disappeared.

Now, ACT for the Disappeared is trying to provide some hope to the families of the missing. They’ve created a website, Fushat Amal, which means a “space for hope.”

“Through this space we can…reinforce their right to know,” Soussi says.

Families can post what they know about their missing relatives — but it’s also a forum for people to provide information about the missing, even anonymously.

So far about 100 families have posted their stories and Soussi says they are getting more requests all the time. It’s also a way to put pressure on the Lebanese government to do something for the families.

“What the government should have done long time ago is to seriously investigate the fate of these people and inform the families of their whereabouts and their fate,” Soussi says.

In 2000, the government conducted an inquiry into the missing, but didn’t handover the files until 2014. Even then, the report didn’t contain information on specific disappearances or people.

Soussi says that may be because many of the politicians in Lebanon’s government today were the warlords of yesterday.

“They might be afraid of being prosecuted,” Soussi says, though that’s not what most of the families want. “[They] just want to know the fate. Just tell us the fate and let’s just close this file and move on.”

Samia Abdullah digs through a drawer and pulls out a few photos she has of Emad — one of him at the beach playing with her youngest son, another of him on a trip to Germany to visit their brother. She shows me the two things she’s kept of his, a cigarette lighter and a brown pajama top he left at her home. She lifts the shirt to her face and inhales deeply.

Without knowing what happened to Emad, moving on is hard. Abdullah says every so often prisoners would be released from Syria and would say they had seen her brother.

“They said ‘we know Emad Abdullah. He is very thin, always he sick. Sitting alone all the time and not speaking with anyone,’” Samia says.

The last time Samia heard anything about Emad was 2008. Then came the civil war in Syria and with it, hopes that the missing prisoners might finally be released if the Syrian government fell.

Last year, ISIS took over control of Tadmur prison, where many Lebanese were thought to be imprisoned. Local media quickly reported that dozens of Lebanese prisoners had been released. Abdullah and others were hopeful, but it turned out that the Syrian government emptied the prison. The reports weren’t true.

Soussi says many families know their loved ones aren’t coming back — they just want to know what happened.

“Some families will tell you ‘I just want one hair to bury or one bone to bury, and I will become fine. I will be fine.’’