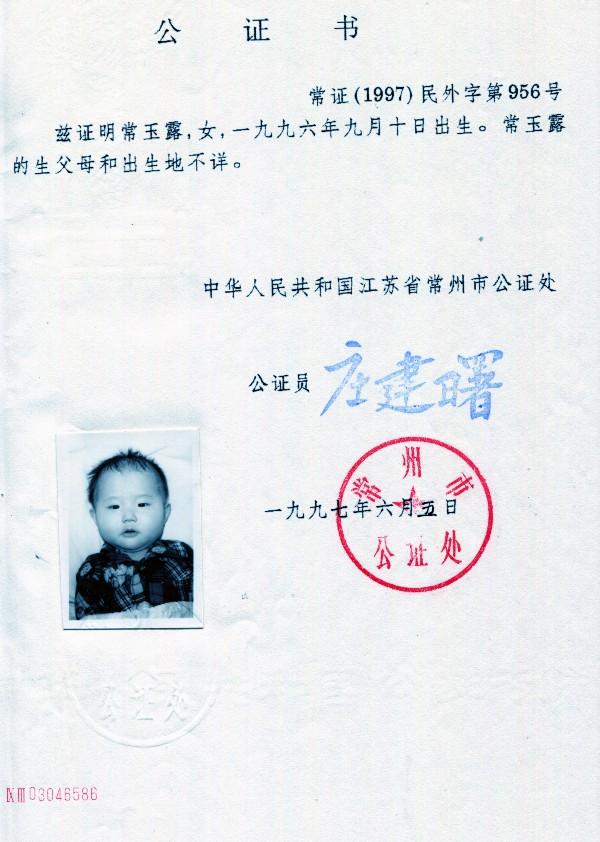

Maya’s caregiver, to my right, placed Chang Yulu in my arms at Changzhou’s orphanage. I placed a fluffy finger puppet in her arms so she’d have a toy to play with.

I adopted Maya in June of 1997, when she was nine months old. Three days after she was born in a rural area of Jiangsu province, she was abandoned in one of the 14 farming villages are known collectively as Xiaxi Town, with some 40,000 residents.

They are sons and daughters of longtime villagers, many of whom married a son or daughter of one of their parents’ friends.

My daughter’s abandonment papers don’t tell us exactly where she was found. They tell us only that local police drove her 15 miles from Xiaxi Town to the orphanage in Changzhou, a city of several million.

The orphanage staff gave her the surname Chang. It is the same surname they gave to hundreds, if not thousands, of babies, nearly all of them girls, who took up residence in its second-floor rooms in wooden cribs arranged in long lines of light blue. Her given name became Yulu. Some babies shared a crib.

Because my daughter was on her back day after day, she used her arms and legs as toys. Soon after her caregiver placed Chang Yulu in my arms, I began playing with her with the white fuzzy finger puppet animal I brought as her gift. Right away, I noticed how she pulled her legs, as if by instinct, toward her head, wrapping them all too easily around her neck. When we got to America, to our home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, early intervention therapists would visit us each week, working to strengthen her leg muscles so one day Maya would crawl, and then walk. On the night that we celebrated her first birthday, she crawled. Five months later, she walked.

This morning, in this same home where she and I have lived as a two-person family, I was awakened by a text alerting me to breaking news: China was ending its 35-year old one-child policy.

I wasn’t surprised since China has been edging toward this change for several years for the most practical of reasons: After decades of a policy limiting population growth, the country now has too few workers, too many elderly in need of young people to care for them, and far too many men, a result of Chinese families’ long-held preference for sons that has been accentuated by its one-child policy.

In November 2013, China had opened the possibility of having two children to couples in which one parent had been raised as an only child. Yet, relatively few families registered for the right to have a second child. China watchers, seeing this, predicted that the abandonment of the one-child policy would happen soon. Now it has.

I’ll be watching closely in the years ahead to see how this two-child charge of China’s leaders affects the intense pressures already being put on its well-educated young women to adjust their lives to fit their expected family roles of wife and mother. It’s considered now a young woman’s duty to be a bride by her mid-to-late 20s.

Due to the gender imbalance brought on by the one-child policy, there are some 30 million surplus men of marriageable age, and these men need brides. In poorer regions of China, sex trafficking has been one way of supplying brides from bordering countries. But for urban women who might not be so interested in reducing their own ambitions for a marriage at a younger age, there is already a popular slang term that stigmatizes them as “leftover women.” This morning a close watcher of women’s rights in China tweeted that this new second-child policy could be summed up in this way: “Hurry up and have two children, leftover women.”

So that is my intellectual response to China ending its one-child policy.

The other Chinese woman I thought of this morning was the person who texted me the news. Simeng is a graduate student from China, studying at a university in Boston. She and I have become good friends, and as we have she’s shared with me the story of her own girlhood in China. She explained how her life was shaped, too, by the one-child policy. She has started writing about her life as one of the millions of China’s “hidden children,” mostly daughters who are born “out of quota,” which means outside the limitations set by the one-child policy. Being “hidden” in China means a child will likely go through childhood (perhaps go through their entire lives) without being registered as a citizen and thus without access to public services, such as medical care and schooling. Soon, Simeng will publish her life story, but she kindly gave me permission to share some of her words about her life as a “hidden child” with you.

Letter to a Once Black Child

As much as I love my sister, I am jealous of her. Not because she’s almost three inches taller than me nor she has a great sense of humor, but that she was raised by my parents, what I, once a “hidden daughter” or a “black child,” did not/could not experience.

Once “Black”

I had very limited memories of my childhood.

I was told that I was transported on a motorcycle by my aunts at night to a family in a nearby village when I was 28 days old and lived there until age five.

Because I am a GIRL. …

I was told by my aunt (my mom’s youngest sister) that she visited me time to time and bought me clothes. But I’ve never heard that my parents had ever visited me.

I only remembered that I was sitting on a big bed and crying alone in that family. No one was there with me.

I wish I could travel back to that point, so I could give that little me a hug and tell myself there is someone cares about you and loves you.

My heart aches for my friend, Simeng. This same heart overflows with love for my daughter, Maya. And from my heart comes a mother’s wish that somehow the woman and man who gave my daughter life know how deeply she is loved, how healthy and wise and curious she has become, how she has always looked for ways to brighten other people’s lives, and how she warms the hearts of all who come to know her.

Melissa Ludtke is a veteran journalist who is producing Touching Home in China: in search of missing girlhoods. She has published essays on Medium including “China’s One-Child Daughters.” In her more recent essay, “Dear Xi Jinping: I am writing to you as an American Mom of a 19-year old Chinese daughter,” she compared what it was like to be a young girl in 1960s and 1970s America to the struggle for women’s rights in China today.