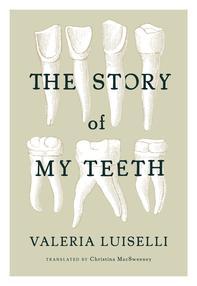

A Story You Can Sink Your Teeth Into

The Story of My Teethis the latest novel from writer and world-traveler Valeria Luiselli. Born in Mexico City, Luiselli spent her childhood and early adulthood moving from one place to the next, living in South Korea and South Africa and India before finally settling in New York City. In this book she draws on her family history and tableaux of Mexico to tell the story of an enterprising man — half auctioneer, half raconteur — known as Highway. Based in part on Luiselli’s uncle, a salesman at the gigantic Central de Abasto market in Mexico City, Highway is a guy who can sell anything. He cooks up elaborate backstories, spiked with literary and historical allusions, to entice buyers towards his random lots (which include, as the book’s title suggests, his very own teeth, plucked from his very own jaw).

As strange and beautiful as the novel itself is the backstory to its creation — a tale that involves a juice factory, a world-class art collection, and a rather unlikely collaboration.

Kurt Andersen: The book is dedicated to the Jumex factory staff. So, who are the Jumex factory staff and how did they get mixed up in your novel writing?

Valeria Luiselli: Jumex is a factory that produces juice, and they have a kind of juice monopoly in Mexico. And they have a big contemporary art collection, a very important and well-known art collection. So the factory and the gallery co-existed in this world, but they also lived in kind of parallel realities that never completely touched.

Workers and rich arty snobs?

Basically yes, that’s it. And so the Jumex Gallery asked me to write a fiction piece for an exhibition that they were putting together. But I want to write for the workers in the factory and not really so much for the gallery space. And they said, well, OK fine, let’s try it. So basically I sent one installment each week and [the workers] formed a kind of reading group. They would critique my work, and then they would just start telling their own stories, which I then always used in the next installment.

So you’re writing for factory workers, did you think, I have to make this simpler, I can’t refer to Virginia Woolf and things like that?

No, I think that’s silly. What I did think was: I have to write something that pulls them in and entertains them after a day’s work at the factory. And that’s a big challenge, to not lose their attention, to keep them interested and motivated so they would still come to sessions every week. It was exactly, I guess, like writing a novel in installments in the late 19th century.

Writing prose fiction is by its nature a solitary, sometimes lonely, occupation. Did doing this change the process, make it feel different to anything you’ve ever done?

It did. I have never had so much fun writing, never in my life. And I didn’t know it was going to be like that. When the first recording came to me and I heard them read out loud and discuss and critique and have fun and laugh and tell their stories, I was mesmerized. I felt like I had just opened a door into a paradise. And I thought, well, it’s going to be really boring to go back to writing the way I’ve always written.

In the afterword you talk about this tradition that I didn’t know about, of cigar readers in Cuba. Describe that.

The idea to write in installments for workers came from that. It’s something that’s been there in the Latin American tradition, primarily in Cuba and transplanted to Mexico. Cigar readers are basically people who read [aloud] while others are doing a very repetitive task. And it was really important in Cuba because it was the way in which, for example, thousands of people heard Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky. Now the tobacco readers in Cuba still exist, but I read an article that said that the big classics have been replaced by things likeFifty Shades of Grey.

So the revolution is over.

The revolution is over.