Bob Woodward and the last of the president’s men

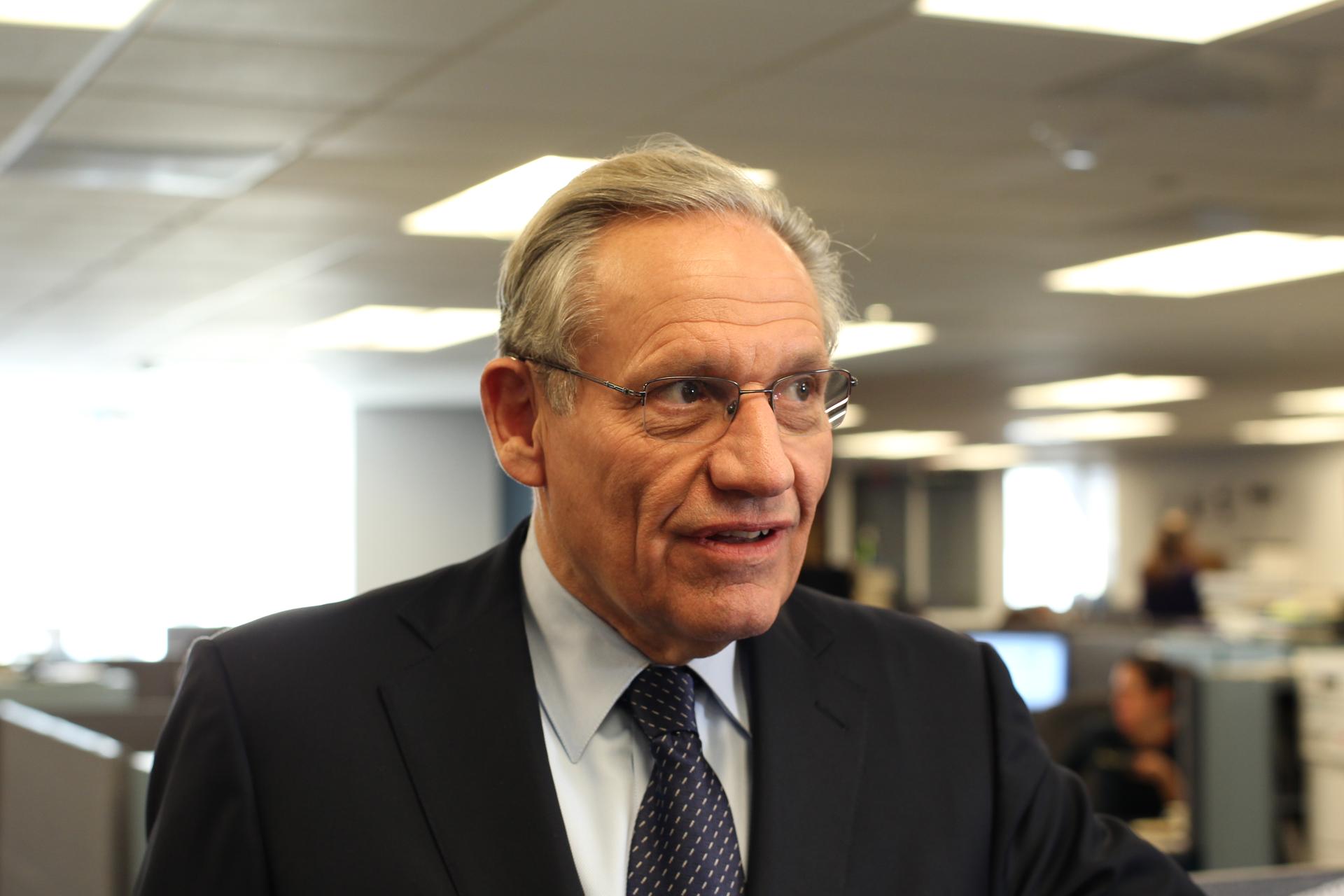

Bob Woodward

It’s been more than four decades since Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein broke the Watergate story for the Washington Post. In 1973, Alexander Butterfield, President Richard Nixon's deputy assistant, decided to disclose the existence of Nixon’s secret recording system in the White House to the Senate Watergate committee.

The big reveal sealed the president’s fate and changed the course of history. Nixon resigned a year later.

In his latest book, "The Last of the President’s Men," Woodward returns to the story of Butterfield and Nixon, delving into hours of interviews with Butterfield, a draft of an unpublished memoir, and an archive of documents from Nixon’s presidency.

“I thought I was done with Nixon,” Woodward says. “[I wrote] four books about him, two of them with Carl Bernstein, and then I went out to Butterfield’s place in California with 20 boxes of documents, some of them never seen before.”

According to Woodward, Butterfield took a trove of thousands of documents from the White House after Nixon’s resignation in 1973.

“Watergate is the management of the political system by Nixon to spy on and sabotage the Democrats to win election,” Woodward says. “It turns out that Nixon was managing the Vietnam War, one of his greatest responsibilities, in order to win re-election, and it is shocking.”

One striking piece Woodward writes about is the “Zilch” memo. In the note, which Nixon wrote sideways across a top-secret document, the president updates Henry Kissinger, then his national security adviser, on war developments. Nixon wrote: “K. We have had 10 years of total control of the air in Laos and V.Nam. The result = Zilch. There is something wrong with the strategy or the Air Force.”

Meanwhile, Nixon had been publicly declaring for three years that the bombing had been effective, and even went as far as to order more bombings.

“Just the night before, he had said in a nationally televised interview that it was very effective,” Woodward says, “You connect the dots with other tapes and documents, and you realize that this is all about winning re-election. Not the war, which, he acknowledged, at least the bombing, achieved zilch.”

In "The Last of the President’s Men," Woodward describes these tapes as revealing a White House “full of lies, chaos, distrust, speculation, self-protection, maneuver and counter-maneuver, with a crookedness that makes Netflix's 'House of Cards' look unsophisticated." According to the author, these tactics were not above pettiness, either, including a story about Nixon’s reaction to seeing pictures of President John F. Kennedy in the White House.

“[Nixon] was walking around the staff offices and saw that some people had pictures of JFK, and he came back and told Butterfield — who was this guy who would do anything Nixon asked— ‘this is an infestation, we have to get all of the JFK pictures out of these offices.’ And Butterfield launched an investigation and got all of the JFK pictures out and replaced them with Nixon pictures,” Woodward says, “It’s astonishing, in [Butterfield’s] final memo, directed to the president, is entitled, ‘sanitization of the staff offices.’ You see that throughout this … the rage that Nixon felt for anyone who had things handed to them, and he goes off on this years and years later. There’s no inner peace.”

Woodward’s access to the documents came only after Butterfield sat on them for 40 years, never telling the story.

“I have the luxury of time,” he says, “I ran into Butterfield a couple of years ago, we started talking, and I thought that I had better go see what he’s got. Everyone who comes from the White House, Supreme Court, or the CIA takes a box of documents and puts them in the attic. Of course, Butterfield had 20. [I told him] we need to tell this story, because this is another dimension of the monumental corruption of Richard Nixon.”

This interview originally aired on the WGBH News program Boston Public Radio.