A journalist tracks what led up to the Boston bombing and reflects on her own immigrant life

Patimat Suleimanova, the aunt of the Tsarnaev brothers behind the Boston Marathon bombing, holds a photo from the family archive at her house in Makhachkala, the capital of Dagestan, Russia. Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, center, is with his brother, Tamerlan, and their sisters.

A life sentence or the death penalty. A federal jury will soon decide which sentence Dzhokhar Tsarnaev will get for his role in the April 2013 Boston Marathon bombing, which killed three people and wounded 264 more. His older brother, Tamerlan, died in a police shootout. He was 26. Dzhokhar is 21.

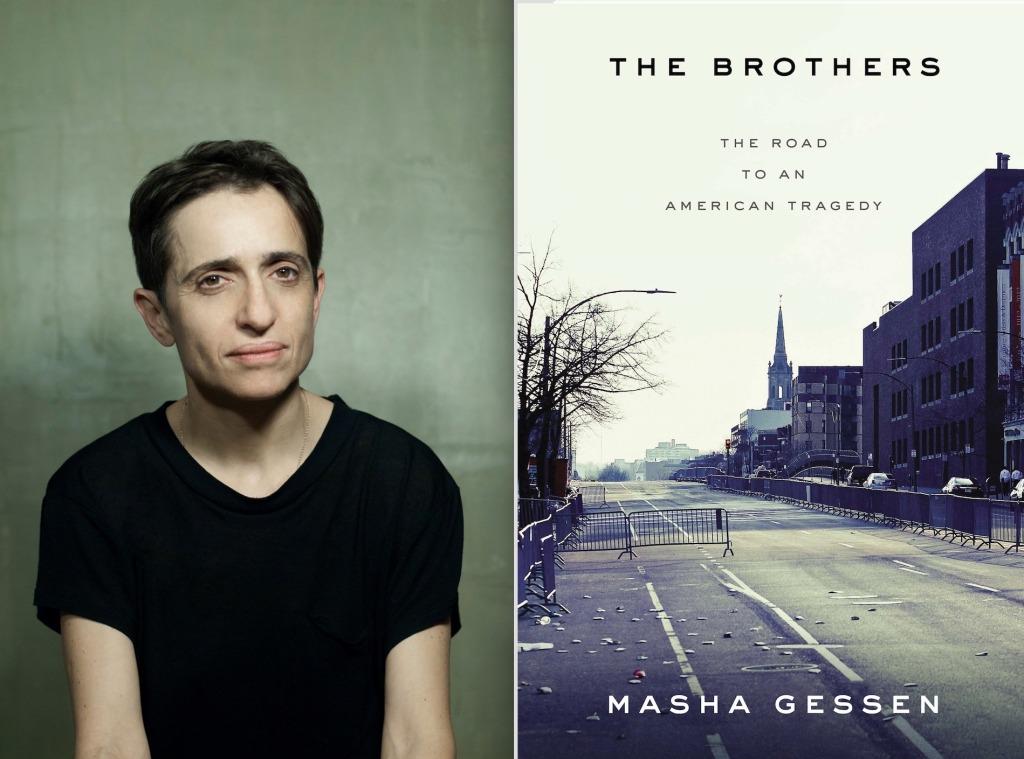

From the start, journalist Masha Gessen has tracked the Tsarnaev family's story. For years, she reported from parts of the world linked to the Tsarnaevs, including Chechnya. She also knew what it meant to be a young immigrant in the US, like the Tsarnaev brothers, having moved with her family from Russia to Boston when she was a teenager. Gessen, who now lives in New York City, spoke with The World’s Monica Campbell about her new book “The Brothers: The Road to an American Tragedy,” and her own immigrant experience.

Q: How did your own immigrant background help your reporting?

I came here when I was 14, about the same age as when Tamerlan got here. My younger brother was also about the same age as Dzhokhar. I thought, “What’s the difference between us?” We both landed in fairly supportive and established immigrant communities, the Russian-Jewish community in Boston. There was mutual aid, like the Chechen community in Boston. We didn’t have much money either, a little bit of welfare-level financial help since we arrived as refugees.

The biggest difference was just the sense of intellectual entitlement. My parents were taking us to the United States so that we would go to the best universities here, the Ivies. That was truly the single articulated goal for our immigration. And that made me feel that I really had the right to get into a great school. I don’t think they [the Tsarnaevs did]. I think it was like this pipe dream, and nothing ever really worked out. You can trace that with Dzhokhar. He was a good student with good grades and then chose the least competitive of the schools that he got into.

There were also things I had an understanding of and knew to ask questions about because of my own experience. But first I need to point out that you can never assume that somebody had the same experience as you. I don’t have the experience of being a Muslim who moved to this country post-9/11, and I don’t want to universalize my experience to that because it is very different, very specific and very painful. But there are certain things that I wouldn’t have known to ask if I hadn’t gone through it myself. Things like how kids separate themselves from their family. I also asked about identity, how the brothers explained that. They would say that they’re Chechen, and nobody had heard of Chechens and they’d say to them, “So, you’re Russian.” And they’d say, “No!” and then have to explain that.” Then they’d say they were Muslim, but they hadn’t actually been observant. I knew enough to ask how they navigated this.

Q: What else did you find about how the brothers presented their identities?

They had different strategies. Surprisingly, Tamerlan’s strategy was to let it go. He would just start saying, “I’m Russian, and my name is Timberland, like the shoe.” Nobody could pronounce Tamerlan. And Dzhokhar actually put more of an effort into explaining where he was from and calling himself Chechen. But even that isn’t accurate. They were Chechen-identified, but they weren’t from Chechnya. But how were they going to explain that they’d spent most of their lives in Central Asia and how come Kyrgyzstan is 1,500 miles from Dagestan? That’s ridiculous.

Even a year after the bombing, I was interviewing someone who was a classmate of Dzhokhar’s, someone who’d been severely traumatized about what happened, and I asked her, “What did you know before all of this?” I asked her what she knew about Dzhokhar.” And she said, “Well, I knew that he was from the Czech Republic.”

But on a more general level, all identities are imagined, all identities are contextual. And the huge issue with this — and the tragedy I describe in the book — is that jihadists and terrorists can be a really tempting identity under certain circumstances. It gives you a sense of belonging. There’s real danger to this disjuncture of identity and expectations for immigrants, and the lure of something grand that offers you a very clear identity and a sense of belonging, and a sense of greatness — all in one package — that is particularly resonant for immigrants.

Q: What do you think about the public perception of the Tsarnaevs?

The whole narrative is this one of good immigrants and bad immigrants. The good immigrants are the ones who are, on the one hand, assimilated, and on the other hand have an intelligible immigrant identity. So Dzhokhar’s social success was partly attributable to his assimilation, but partly attributable to the fact that he had an intelligible identity. He put himself across as a refugee from a war zone, which is not entirely inaccurate, but a gross oversimplification of what he had gone through. It was intelligible, it was acceptable, and combined with his Americanness, it was just perfect. So he earned his stripes as a good kid by doing that, by doing exactly what’s expected of him. That’s his strategy, and that’s a good assimilation strategy. Just mirror back whatever is expected of you. Never have any meaningful interaction with anybody, never get into any depth, but get really good at mirroring.

Tamerlan wasn’t so good. He wasn’t intelligible. He was difficult, right? So he’s a bad immigrant. And what’s interesting is we’re going to be seeing a lot of this narrative come to the surface in the second phase of the trial. The defense is going to push that line, saying “Look, Dzhokhar is a good immigrant, a regular American teenager who had a bad immigrant brother who led him astray.” It’s just going to reinforce many of the things that are wrong with the way we think about immigration.

Q: The story we hear about the Tsarnaev brothers is that they did a lot of solo navigating here, that their parents were absent from their school life. But you point out how that can be a typical part of immigrant life. What did you notice?

The Tsarnaev brothers kept their home life and their school life completely separate. And that’s a very difficult immigrant situation. You hang out with your friends at school and you never invite them home. You know they’re going to be completely weirded out by the food you eat, and just the way it smells. You know that everything is different. And I’m not talking about Muslim dress or anything like that. I’m just talking about immigrants. So it makes perfect sense to me that the Tsarnaev’s landlady, Joanna Herlihy [who lived in their building], who was a lovely Cambridge lady, went to Dzhokhar’s middle school graduation. She would fit in.

Q: What was your own balance like, between home and outside life?

Once or twice when my non-Russian friends came over to the house, it was a disaster. They didn’t want to eat the food, I was embarrassed. The usual. It happens to every immigrant kid I’ve ever talked to. And when it came to my education, my parents had almost zero involvement. They were in their mid-30s when we got here and I’m still awed by what they did because they’d never traveled to the West. They just took two children and jumped into the abyss. It was completely disorienting for them and it was very difficult to see my parents become incompetent. They’d always been grown-ups and suddenly they weren’t. If I needed to do something, I needed to do it myself. They were in no position to help me navigate the school system. So I went to the Boston Public Library and checked out college information books and SAT prep books and spent every afternoon at the Boston Public Library for like a year, basically learning everything I could about applying to college and studying for tests.

And then I just left town. I had the bad sense to graduate from high school early, and my parents had the bad sense not to hold me back. So I skipped a couple of grades, graduated early — I was 16 — and got into Cooper Union. I got a grant to pay my housing expenses, and I also had student loans. It wasn’t a huge financial burden, but there was always that sense that there’s no rear, nobody who will bail me out. That’s stayed with me. I’m 48 and pretty comfortable now, but I’m still constantly worried.