South African partnership hopes to prove text messages can save the lives of mothers and children

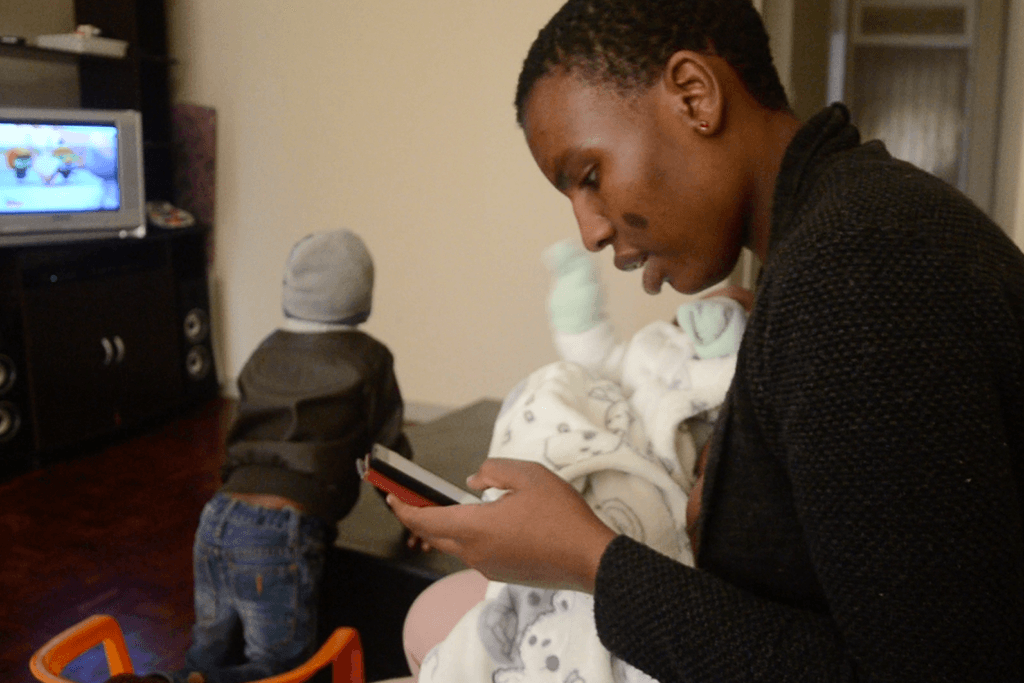

Sikhomzile Sibanda, a participant in the Mobile Alliance for Maternal Action (MAMA) program in South Africa, looks through her text messages. MAMA aims to inform pregnant women and new mothers via text messages.

JOHANNESBURG, South Africa — It was a sleepless night for Sipho Mpofu and her one-year-old son, Junior. After days of vomiting, the boy was squirming restlessly in bed with a high fever. Just as Mpofu’s concern edged toward despair, she remembered a text message she had received several months earlier that recommended giving a solution of salt and sugar to a baby with an upset stomach.

She did, and by the next morning Junior was back to his playful self.

“Mother was very worried about you last night,” she told him with a tone of relief on a recent summer morning.

The guidance had come to Mpofu’s cell phone as a text message from the Mobile Alliance for Maternal Action (MAMA), an international initiative to reduce maternal and newborn deaths by providing new and expectant mothers with health information through mobile devices.

Mpofu was able to treat Junior’s extreme dehydration, but recently a friend of hers who was not in the MAMA program buried her two-week-old child after similar symptoms went untreated. After the death, Mpofu asked her friend if she had made the salt-and-sugar solution. She hadn’t.

It is preventable deaths like these that the MAMA project hopes to avert. According to UNICEF, in South Africa the child mortality rate has fallen from 61 deaths per 1,000 live births in 1990 to 45 in 2012. But that is still higher than targets set for the country in the United Nation Millennium Development Goals. And some 1,500 women died from pregnancy and childbirth-related causes in 2013, according to the World Health Organization. This figure has changed little from where it stood two decades ago.

MAMA is an example of a public-private partnership (PPP), a collaboration of governments, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), private companies and other entities that get together to fund projects and implement programs that address some of the world's most challenging health and development issues.

Launched three years ago, MAMA is a joint effort led by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and Johnson & Johnson, with active projects in South Africa and Bangladesh, and planned rollouts in India and Nigeria. It is also one of many so-called mHealth programs begun in recent years, seeking to leverage the rapid growth of mobile phones to address vast public health needs in developing countries.

Through MAMA South Africa, registered pregnant women and new mothers receive text messages twice a week that guide them through their pregnancy and the first year of their children’s lives. The MAMA text message program reaches 12,000 women in six clinics in Johannesburg, the nation’s largest city. It also has an online component that reaches hundreds of thousands of women nationally through informational, interactive sites and weekly quizzes.

Encouraged by anecdotal evidence, the country’s minister of health announced in August that the government will adapt a version of MAMA’s text messaging program in the coming months with a goal of eventually reaching the one million or so pregnant women who give birth in the public health system each year. In South Africa, the unique subscriber mobile penetration rate is 64.6 percent.

But a close look at MAMA shows that despite its good intentions, this particular public-private partnership faces roadblocks in proving itself. Some members of the public health community are raising questions about the program’s long-term sustainability and efficacy.

While mothers in South Africa have testified to the helpfulness of the program, there are concerns about the high cost of text messaging. And given the lack of strong evidence of positive health outcomes from the program, some critics are asking if limited government funds should be used to pay for text messages when they could be paying for more nurses instead.

The Cost Barrier

MAMA’s global partners began to merge in late 2010 as Johnson & Johnson began conversations with USAID. They each decided to commit $5 million to the MAMA project over three years. Then new partners came into the fold and an operating plan was hatched. Johnson & Johnson brought on a subsidiary, BabyCenter, to provide the health content for the text messages. Then came the UN Foundation, which already had experience working on mobile health projects. It, in turn, brought on the mHealth Alliance, a UN initiative that would provide mHealth expertise to the partnership.

Part of the reason MAMA was conceived, says Kirsten Gagnaire, the program’s executive director, was to scale up mHealth pilot projects. Despite the proliferation of these projects since their early days in 2003, many have not gone beyond the pilot phase, says Patricia Mechael, executive director of the mHealth Alliance.

Secretary of State Hillary Clinton introduced the MAMA program a week before Mother’s Day in 2011, calling maternal and child health a priority to her personally, as well as to the Obama administration.

“It's clear that with the right tools, the right partnerships, and the right commitment, we can achieve real results,” Clinton said.

The global MAMA partner organizations recognized from the start that they would need a strong local presence to implement their vision. They recruited regional partners from the public and private sector across all three countries they sought to work in initially: Bangladesh, South Africa, and India. In South Africa, the MAMA project recruited four organizations: telecommunications giant Vodacom and local nonprofits Praekelt Foundation, Wits Reproductive Health and HIV Institute, and Cell-Life.

The idea was that MAMA would negotiate discounted prices with Vodacom to send up to 172 text messages to women at a fraction of the going rate. Vodacom provided MAMA with additional funding, as part of the company’s corporate contributions, which would then purchase the text messages through a third-party provider. Not all women were on the Vodacom network, of course, so for those who were not, the organizations secured additional funding from global partners.

Attempts to secure a discounted text messaging rate from Vodacom were met with resistance, however, and additional telecom companies did not sign on as organizers had hoped they would. MAMA’s inability to negotiate a lower price meant that it could not reach as many women with those funds, according to the Praekelt Foundation.

Women who sign up for MAMA get text messages from the program for free, but the texts are not free for MAMA. The program has to pay up to $4 for each woman who signs up if she receives the full set of messages. Prices are higher in South Africa than in other African nations, according to Craig Friderichs, program director at GSMA, a telecommunications trade group.

The cost of the service has curtailed MAMA’s reach; the text messaging program currently operates in only six clinics in Johannesburg because it can’t afford to expand. It is able to reach a total of 544,000 women through additional informational websites and weekly quizzes, but because this information isn’t directly delivered to women based on the stage of their pregnancy or post-pregnancy, these other messages are not catered and delivered to the individual.

“The cost of sending an SMS, making calls, using data, the rate that we can get them negotiated to, has everything to do with how many women we can serve,” Gagnaire says.

Mpofu learned about the MAMA text messaging program while sitting in line at a clinic near her house in Johannesburg. Someone affiliated with the program was there explaining it to the women waiting for their appointments, and Mpofu decided to sign up. Junior was six weeks old at the time, and although Mpofu had already had four children before Junior, she says she is still learning from the text messages she receives.

Mpofu, who is 38 years old, earns about $230 per month as a housekeeper. Her husband sells airtime for mobile phones. Together they can barely pay school fees or for food for all of their five children.

“I don’t like the work I’m doing, but I do it because I’m desperate,” she says. “Life is stressful, and Johannesburg is so expensive.”

Mpofu is the kind of woman MAMA hopes to target: women who might not have access to high quality health information and care and who are more likely to suffer from preventable illness and death.

According to the World Health Organization, every day approximately 800 women die from preventable causes related to pregnancy and childbirth, with 99 percent of all maternal deaths occurring in developing countries. Maternal mortality is higher for women living in rural areas and in poorer communities. Of the 12,000 women enrolled in the program, about 88 percent live in households with monthly incomes of less than $460.

MAMA never had plans to expand its text-messaging program in South Africa because of the high cost of the messages, Gagnaire says. But with the government’s launch of its text-messaging program, called ‘MomConnect,’ every woman in the country will have access to the government’s texts. Still, MAMA needs funding to maintain its own programs in the country.

The government is hoping to bring on board all of the nation’s network operators with a reduction in prices to at least half their commercial value, says Dr. Yogan Pillay, deputy director for HIV/AIDS, TB, and Maternal & Child Health at the National Department of Health. One of South Africa’s cellphone network operators, MTN Group Ltd., says that the company would have to analyze the proposed arrangement to find out how it could be profitable in the long run.

Pieter Verkade, group chief commercial officer for MTN, calls finding a commercial interest in the program “crucial” for the company’s involvement.

“We have to look at what commercially is in it for us,” Verkade says. “If it’s a one-off, that is possible. We’ve done that before. But if it becomes a commercial service, it becomes something else.”

A ‘Bold Move’

So far, the primary evidence to show the success of the MAMA text-message program came out of a focus group held last year hosted by MAMA partner Wits Reproductive Health and HIV Institute. Mothers there said they valued MAMA for the information it provided on such things as vaccination and developmental milestones.

The MAMA South Africa program has raised about $1.1 million for the first three years. Eighty-five percent is funded by the MAMA global core partners, the remaining 15 percent from the regional partners. The funding for the South African government’s ‘MomConnect’ program will eventually come directly from the government’s health budget, Pillay says.

Johnson & Johnson and ELMA have each committed $500,000 to help the program in the launch period before the government’s budget takes on the expense, and the US government — through PEPFAR and the USAID Southern Africa mission — is supporting both the expansion of MAMA and the launch and roll-out of ‘MomConnect.’

If the MAMA program were extrapolated to a national scale, the text messages alone would cost the government around $4 million per year. This is given the commercial prices. But the government is hoping that network operators will reduce the price of the text messages.

The South African government announced the launch of MomConnect a little more than a year after MAMA began registering mothers in South Africa, without a solid base of evidence to show the outcomes of the program.

“This was a very bold move,” says Sara Nieuwoudt, a lecturer at the School of Public Health at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg who works in the division of social and behavior change communication. “If I’m a domestic worker and I am told by a message that I need to breastfeed my child exclusively, but I need to travel a half-hour between my work and my home, where my child is, it becomes impossible. If you are telling people certain things but not addressing other more critical systematic barriers, it becomes problematic. This program could be a sexy thing for a while, but if the government isn’t able to develop an evidence base, then there is an ethical issue raised of how to best use resources for public health.”

“I think the efficiencies of mobile are unquestioned,” says Alison Chatfield, project manager at the Women and Health Initiative at the Harvard School of Public Health, citing the fact that mobile phones can, for one, reduce the time it takes to connect health provider with patient. “Where it gets stickier is when asking, can mobile technology increase the quality of care that is being provided to the patient?”

But seeing even a general improvement in maternal and child health outcomes won’t be enough of an evidence base, according to Alain Labrique, associate professor at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, who recently joined MAMA’s advisory board.

“Things naturally get better over time,” he says. “I could sit in a room and send myself text messages and say my behavior improved. The challenge is showing that the change is because of a program.”

The MAMA program is aware that it needs to develop an evidence base moving forward.

“Evidence of whether and how our work impacts the lives of moms and babies is a priority for MAMA and has been since our inception,” Gagnaire says.

Several studies are now under way, Gagnaire says, looking at changes in participants' knowledge, planning, self-efficacy and at-home behaviors, and tracking whether they seek clinical services. The South African USAID mission has allocated $200,000 for evaluation of the MAMA program and is waiting on government approval to move forward with collecting data. Wits Reproductive Health and HIV Institute will conduct a retroactive survey on users of the program that are HIV positive. The South African government also will deploy Johns Hopkins University, the University of the Western Cape and the University of Stellenbosch to develop an evaluation system of the MomConnect program.

The South African government has also leaned on positive results from Text4baby, a free text messaging service for mothers in the US, according to the MAMA team. Johnson & Johnson was a founding sponsor of the program.

Debbie Rogers, lead strategist for the Praekelt Foundation, thinks the government takeover could be a proof-of-concept project.

“MAMA has essentially been taken over, scaled up and made sustainable,” she says. “There are so many people all over the world talking about how to make that happen, and it’s actually happened here.”

But others are watching the launch with concern.

“We used to have health educators helping women,” says Dorothy Matebeni, president of the Democratic Nursing Organisation of South Africa, a national trade union. “No woman would leave a maternity ward or antenatal clinic without education. I should think that we need to revive those things.”

Matebeni says making a connection between a nurse and a woman is better than spending millions on text messages.

“We used to have systems in place,” she says, shaking her head.

For women like Mpofu, who witnessed a friend lose her child to dehydration, receiving a health-based text message is a godsend. But whether the government should be spending its budget on text messages rather than putting funds into paying more nurse salaries or other current programs within the national health system is another question, Matebeni says.

More from GlobalPost: Merck continues campaign to hold off river blindness in the DRC (VIDEO)