Crimean militia leader accuses US of orchestrating Ukraine’s unrest

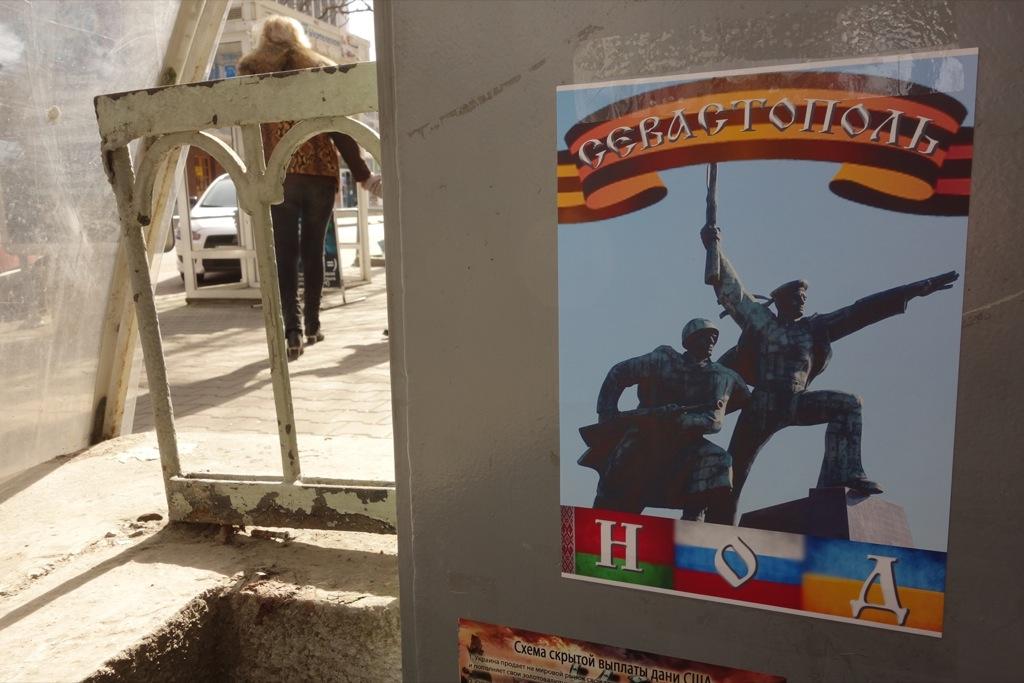

A sign at the head office of Crimea’s People’s Liberation Movement reads, “Sevastopol NOD.” NOD is the Russian acronym for PLM.

SEVASTOPOL, Ukraine — Before the Crimean crisis started, Aleksey Borsuk was a freelance journalist.

Now, he is the leader of the People’s Liberation Movement (PLM), one of about a dozen volunteer “self-defense” forces that have formed in Sevastopol, Crimea’s largest city, purportedly protecting the region from outside attack.

“The founding ideology of our group is that the US stands behind all of the disorder in Kyiv, and it is seeking to submit the country to economic slavery,” he said.

Borsuk said he formed the group shortly after pro-Western demonstrators toppled the government of President Viktor Yanukovych and installed an interim government ahead of May elections. At the same time, thousands of Russian troops in unmarked uniforms surrounded Ukrainian military positions across the peninsula. Borsuk said he views the change of power in Kyiv as a Western-backed coup.

Although the Russian soldiers appear to be doing the heavy lifting in Crimea, a constellation of volunteer “self-defense” groups has filled in the gaps and formed the more visible face of the occupation.

Borsuk’s movement, the PLM, operates a checkpoint between Sevastopol and the city of Yalta, and is also taking part in the ongoing siege of the Ukrainian Navy Headquarters. The self-defense groups are diverse in ideology; some are communists, some are Cossacks, some are veterans of the Soviet war in Afghanistan, Borsuk said.

The PLM differentiates itself by its specific stance against the United States and the dollar as an international reserve currency. Although he agreed to be interviewed by GlobalPost, Borsuk said the movement also counts among its enemies the foreign press, as well as the Soros Foundation and other Western NGOs.

![]()

Alexei Borsuk gestures toward signs in the PLM offices. The sign on the right says, "Registration point for families suffering from the German-American intervention." With a smile, Borsuk adds: "I politicized that one a bit." (Filip Warwick for GlobalPost)

Unlike most of the “coordinators” of pro-Russian self-defense groups, Borsuk is ethnically Ukrainian — but he believes Ukrainians and Russians are “one people” who should be united.

Amnesty International and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe have expressed increasing concern over the “self-defense” groups, which have been implicated in numerous attacks against journalists and pro-Ukrainian activists in Crimea.

More from GlobalPost: Your starter kit for understanding the chaos unfolding in Crimea

In one such incident on Sunday, a BBC film crew recorded violent clashes between pro-Ukraine protesters and self-defense groups, including the PLM. The pro-Russia activists then chased the BBC crew out of the area.

“We were seconds away from being beaten up … haven't run so fast for ages!” BBC news presenter Ben Brown said on Twitter. “Now safely back in hotel but increasingly scary for journalists.”

Borsuk said his group was at the demonstration but denied that he and his activists attempted to attack journalists or the demonstrators.

“We don’t beat anyone, we don’t provoke. We prevent provocations,” he said.

At the moment, the PLM is mostly unarmed, Borsuk said — but it is training a “quick reaction force” of men who already have gun permits to be able to respond to “provocations,” with deadly force if necessary. He said the regional government in Simferopol has started giving out new gun licenses to self-defense groups, allowing them to legally arm themselves.

Ivan Komelov, a representative for the Sevastopol city administration, said that the police coordinate closely with the self-defense groups.

![]()

A sign in the Sevastopol PLM offices reads: "We Will Stop the Arrogant Lies of Mass Media." (Filip Warwick for GlobalPost)

Borsuk declined to say how many members are in the PLM, but claimed that their enlistment is growing. Their main goal at the moment is to provide security leading up to the March 16 referendum in whichCrimea residents could vote to join Russia.

More from GlobalPost: Why Russia really wants Crimea

In the offices that the PLM shares with other groups in downtown Sevastopol, middle-aged volunteers phoned people who had offered to help the movement. At another table, a volunteer took notes as she listened to a woman complaining that she had seen someone toss a bag of sandwiches over a barrier to Ukrainian troops whose base has been besieged by pro-Russia forces.

"Something should be done," the woman said. "This person was interfering with the holding of these prisoners [the Ukrainian soldiers]. It's a provocation."

The volunteer told the woman that there was nothing they could do directly, but that the movement would pass on the information to the authorities. Other volunteers chatted in the small office about progress on the movement’s request that fishermen who would be at sea on March 16 be permitted to vote early.

The group’s future is uncertain after Sunday's referendum. Borsuk says their plans will depend on the reaction of Ukraine and the international community, though he doesn't elaborate on how.

On the other side of Sevastopol, Andrey, a member of a different self-defense group, said that he is looking forward to the referendum so that he can go home.

A carpenter, 42-year-old Andrey said he dropped everything to camp out at a checkpoint outside the Belbek airbase, which was seized in early March by Russian forces. He's been here for nearly two weeks.

Andrey said he joined to protect Crimea from an imminent invasion. He declined to give his last name for fear of reprisals.

A media blitz on Russian TV broadcasts in Ukraine’s Russian-speaking East has shown the Maidan movement, as the Kyiv protesters are known, as a fascist insurrection led by drug addicts and militants seeking to kill ethnic Russians. It appears to have had its desired effect on Andrey.

“The only thing stopping the fascists from exterminating all of us in Crimea are groups like us and the support of Russia,” he said.

The Belbek checkpoint is little more than a tent and a fire, where Andrey and his four comrades were busy preparing tea on Saturday afternoon. A military vehicle barricaded the road a short distance away.

Andrey insists that there are no Russian troops in Crimea and that all of the facilities taken from the Ukrainian army are controlled by self-defense forces similar to his own. But when a troop truck without plates pulled up quickly to the checkpoint, Andrey snapped to attention.

A man in his 20s with modern military gear, including an assault rifle and scope, jumped down from the truck and spoke with Andrey in a nearby parked car. After about five minutes, the troop truck sped off as quickly as it had arrived.

“Orders,” Andrey mumbled.

Although there are tense ongoing standoffs between Ukrainian troops and the forces that have encircled their installations, they have so far been bloodless.

Three Ukrainian soldiers at the administrative portion of the Belbek airbase, who spoke on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to speak with the press, said that they had agreed with the Russians that they would be allowed to remain in that section of the base, while the Russians kept to the airfield. Similar arrangements have reportedly been struck at other Ukrainian bases.

But late Friday night, a mix of Russian solders and self-defense group members reportedly rammed open the gates of a base in Sevastopol and stormed in, threatening to shoot to kill if the Ukrainian soldiers did not surrender. After negotiations, the intruders eventually withdrew. But since then, one Ukrainian soldier said, "we now expect the Russians could violate the agreements and storm in here at any moment."

The soldiers say they expect everything to change after the referendum.

"As soldiers we have to prepare for the worst," one said.

More from GlobalPost: A brief psychoanalysis of Vladimir Putin